Table of Contents

Keely Covello

Keely Covello is a filmmaker, writer, and journalist. She is the editor of America UNWON, a reporting project focused on rural and Western issues.

After years of fire and smoke in rural Northern California – evacuations, death and destruction, broken communities, lost homes – watching Los Angeles burn feels surreal but inevitable. This could have been avoided, but we knew it was coming.

For years, we have sounded the alarm to anyone who would listen. San Francisco and Los Angeles ignored us.

Now Los Angeles – one of the great cities on earth, a unique American gem – is in ashes.

For anyone who wants to understand how we got here, this is what happened.

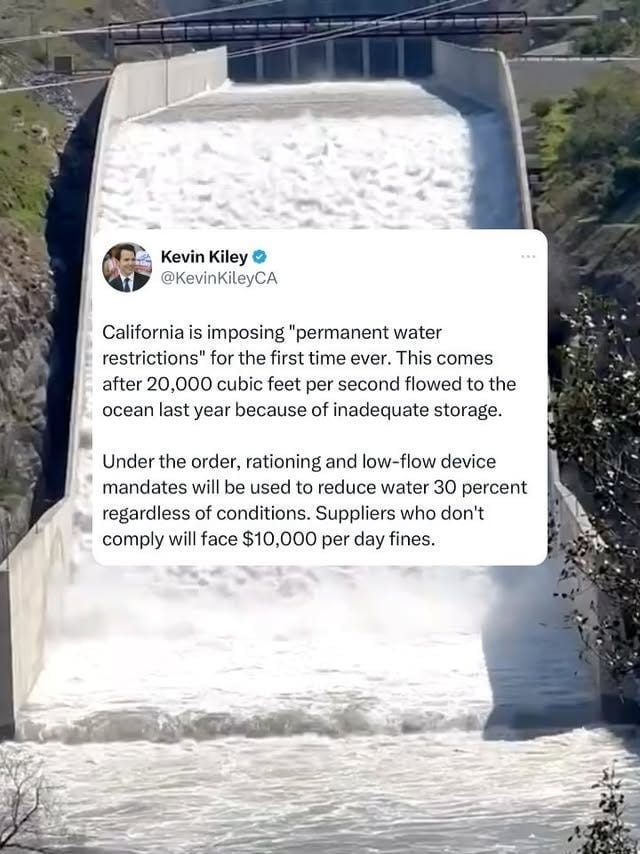

California has not built a new major water reservoir since 1979.

The state’s last major reservoir project was completed in 1979, when the population was some 23 million. It’s been 50 years, there are now 39 million residents, and progress on the storied California Water Project has stopped.

In 2014, Californians voted overwhelmingly for Prop 1, funding a $7.5 billion bond to construct new water reservoirs and dams, with a deadline of January 1, 2022.

It’s now 2025, and no reservoirs have been built. Proposed projects remain mired in the bureaucratic morass of California politics.

There is no reason for California to experience water shortage. The natural climate is cyclical: years of low rainfall punctuated by years of extreme rain. Eleven months ago, at the start of 2024, we were enjoying several extra feet of snowpack in the Sierras and the most rain we’d had in 25 years. The reservoirs were overflowing.

Year after year, massive, swollen rivers in Northern California send water out to the Pacific Ocean, while government agencies scold citizens for watering their lawns.

The state is spending millions to REMOVE existing water infrastructure.

If failure to build new water projects for a growing state population weren’t bad enough, Gavin Newsom and his administration are spending millions of taxpayer dollars to destroy existing water infrastructure in fire-prone Northern California.

The Klamath Dam was removed in 2023.

Scott Dam is next: a century-old dam system upon which some 600,000 people rely in agricultural communities stretching from Potter Valley to Bodega Bay.

The government wants to remove this dam, impoverishing the farm communities and rural residents who rely on it, to “improve salmon habitat.”

Several lethal fires have hit this region in the past few years, including the Redwood Complex and Sonoma Complex fires in 2017, and the Mendocino Complex Fire in 2018. Removing their water is a cruel blow for a community still reeling from those disasters, leaving them defenseless when the next fire comes.

Water cuts to farmers and citizens over a three-inch fish led to empty reservoirs.

Farms were run dry and pumps shut off to preserve the three-inch “delta smelt.”

California is the leading agricultural state in the nation. But for years, politicians slashed water allotments and shut off ag pumps to farmers in an effort to save a finger-length, minnow-like fish called the delta smelt.

When President Trump took office, he said California should consider updating its water infrastructure so farmers could grow crops and cities didn’t have to burn to the ground over a minnow.

This enraged Democrat activists. Their righteous indignation fueled many think pieces about the Delta Smelt.

For all that spilled ink, the restoration efforts didn’t work. Outside hatcheries, the delta smelt are all but gone.

So are scores of farmers, their land run dry by politicians in Sacramento.

This approach is typical of the consistent preference displayed by California politicians for the perceived prosperity of any animal, species, or ecosystem over the welfare and survival of its citizens.

When the fires started in Los Angeles, there was no water in the fire hydrants.

Removing grazing, controlled burns, and management left California an unnatural tinder box

According to UC Berkeley rangeland science professor Lynn Huntsinger, cattle remove some 12 billion pounds of dry biomass from California’s grasslands and woodlands every year.

“Cattle are the largest fire prevention tool we have in the state,” she told me. “But people are largely unaware of it.”

Prescribed fires and forest management have also gone out of fashion. For centuries, Native tribes practiced controlled burning to manage the natural fire risk inherent to California’s ecosystem.

For decades, ideologues waged an all-out war against forest management. Earth First! terrorists drove metal spikes into tree trunks designed to kill or maim unwitting loggers. President Joe Biden appointed one of those extremists to lead the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Seven million acres were named “protected habitat” for spotted owls, turning logging communities in the North into ghost towns and axing tens of thousands of jobs.

All of these efforts resulted in unnatural, out-of-control overgrowth. When the fires raged through, hot and wicked, those “protected” trees and wildlife were destroyed, not with the judicious eye of proper sustainable loggers, but with the fury of insulted nature.

In response, Gavin Newsom cut the budget for forest management. And in October of last year, under President Joe Biden, the Forest Service put a stop to prescribed burning in California altogether.

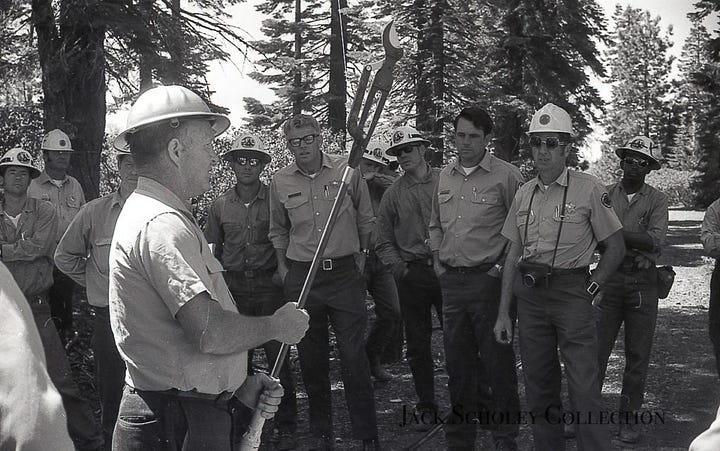

California changed its wildfire approach from expert forest management to militarized fire suppression.

In its slow shift away from responsible, historic land management, California also changed the focus of its fire services away from land and forest management to militarized fire suppression and firefighting. Now we have something new: CAL FIRE.

Equipped with helicopters, air tankers, bulldozers, all-terrain fire trucks, thousands of employees, and hundreds of millions of dollars, the fleet of union-backed firefighters weren’t taking orders from quiet old cattlemen and khakied forestry workers anymore.

In place of tree thinning, controlled burning, forest management, and brush clearing, we had Smokey Bear. Prevention, suppression. Fire forces bought into the delusion that they could eliminate fire from this ecosystem. Instead of using fire as a tool, they tried to ban it. We allowed unnatural overgrowth to take over, turning into billions of tons of dry fuel. So when fires did burn, they destroyed.

In a piece for the Atlantic in July 2022 titled “Trees Are Overrated,” author Julia Rosen suggests the militarized approach of modern fire practices goes against centuries of land knowledge:

Many Indigenous peoples, likely noting the benefits of wildfires for hunting and foraging grounds, intentionally burned the landscape, helping to maintain and possibly expand grasslands and savannas. But in Europe, powerful civilizations took root in forested terrain. And centuries later, when these cultures began exploring and colonizing the rest of the world, they chose trees over grass.

The vast plains of the American West are an ecosystem designed for fire, not heady overgrown brush. In terms of climate impact, grassland is a more effective and reliable carbon sink than forest. One study even found that grasslands may store more carbon through fire than forests lose.

The plains of the American West were not meant to resemble the European forests familiar to our pioneer fathers’ ancestral eye; they were more like the African savanna. This place, in its stark, haunting beauty, was shaped by fire.

We knew it was coming, and yet the city was unprepared.

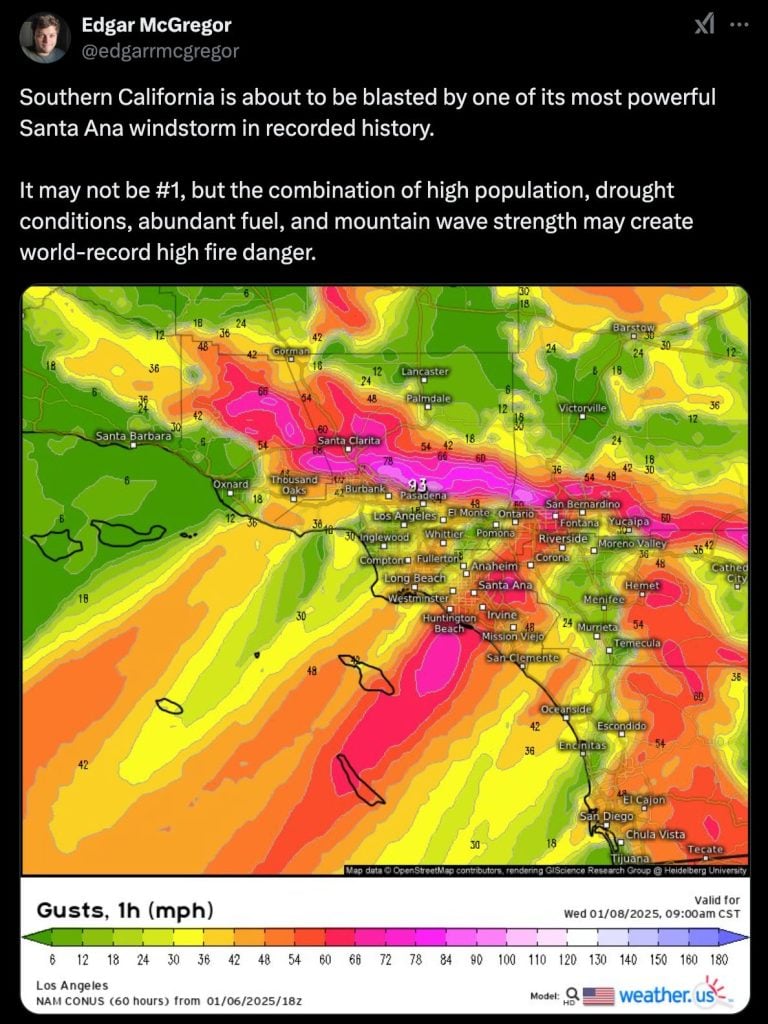

One fact that seems to be lost in the coverage of the Los Angeles fires is this: We had warning.

This tweet was posted Monday, the day before the winds started.

I live in Orange County. Everyone knew high winds were hitting. This happens; dry, fast Santa Ana winds, or “devil winds,” blow from the desert over the mountains, funneling through narrow mountain passes and rapidly heating as they descend.

We’re coming off two record-rain years, but this winter has been dry. With the devil winds near, we were all on watch.

Still, inexplicably, when the fires started, there was no water in the Los Angeles fire hydrants.

The media will still blame climate change. This allows those really responsible to escape accountability.

There were 13,909 “homeless fires” in Los Angeles in 2023.

A few months ago, LA Mayor Karen Bass slashed the city’s fire budget by $17.6 million. She cut the budget for other government functions such as sanitation and street service. These are the items that Californians pay taxes for; one might say they are the only reason to pay taxes.

Her 2025 budget proposal includes $950 million for “addressing homelessness.”

In California, the homeless are treated like a protected political class. Any suggestion to clean up homeless encampments or get the mentally ill and drug-addicted off the streets is met with disdain, as though leaving unwell human beings in squalor, a danger to themselves and others, is the compassionate choice.

It turns out mentally ill people camping in public spaces often start fires. In 2023, 13,909 “homeless fires” were started in Los Angeles alone, almost double the number in 2020. Some are caused by cooking fires, or by tapping into city electrical wires under the pavement.

Between 2019 and 2024, California spent $24 billion to “combat homelessness.” During those five years, the homeless population grew by 30,000 to 181,000. Despite spending the equivalent of $160,000 on each homeless person, the state had nothing to show for it. A 2024 report said the state lost track of those billions of taxpayer dollars, failing to “adequately monitor” its spending.

ESG/climate policies and DEI hiring prioritized over effectiveness and competency.

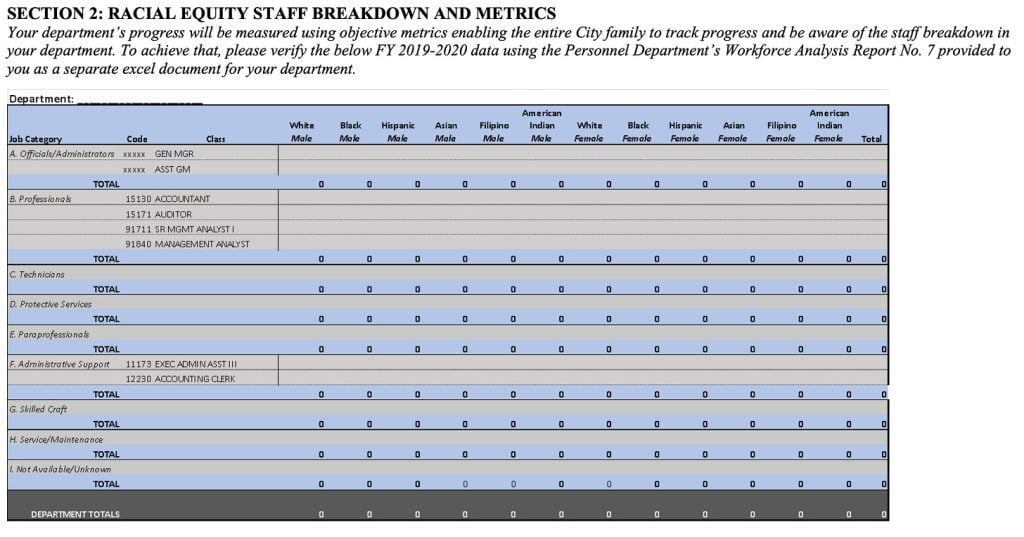

In 2021, the LA Fire Department issued a racial equity plan to “end systemic, institutional, and structural racism” in the force. This plan includes a chart to map out the racial makeup of employees.

The current LA fire chief appointed in 2022, Kristin Crowley, is female and gay. Her stated focus is improving diversity in the force.

Over at the mayor’s office, when last night’s fires broke out, Mayor Bass was in Africa, attending the inauguration of the Ghanaian president on the taxpayer dime.

Governor Newsom thanked her for providing leadership “in absentia.”

Bass, a black woman, won her race for mayor against Rick Caruso, a successful Los Angeles businessman who changed his political affiliation from Republican to Democrat in a failed bid to increase his appeal to LA voters. Caruso was on the ground to discuss the fires with local news crews, and the first person I saw to break the news that the hydrants were not working.

Meanwhile, as 100,000 evacuated Californians prayed their homes were still standing, outgoing President Joe Biden took the opportunity at the press conference to announce, “The good news is, I’m now a great-grandfather.” It brought to mind his equally self-involved press conference in Lahaina after the Maui fires, in which he told a roomful of survivors about the time his Corvette almost caught fire.

State politicians take donations from at-fault power companies while fire victims remain unpaid.

The history between California politicians and state-regulated power companies like Southern California Edison (SCE) and Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) is a long and sordid one.

PG&E has a monopoly on natural gas and electricity services across much of the northern part of the state. The company was responsible for over 1,500 fires between 2014 and 2017, including the 2018 Camp Fire that took 85 lives and destroyed nearly 18,900 homes and buildings.

The 2018 Camp Fire was started by a neglected power line belonging to PG&E.

After pleading guilty to 84 counts of manslaughter in the Camp Fire, PG&E was ordered to pay $13.5 billion to victims. The company filed for bankruptcy.

PG&E has made millions of dollars in donations to politicians like Gavin Newsom, Jared Huffman, and Nancy Pelosi.

In the wake of its new status as a bankrupt convicted felon, PG&E continued to make those donations, spending millions of dollars on lawmakers’ campaigns, treating employees to expensive dinners days before planned power shut-offs, and doling out $11 million in performance bonuses to executives, all while fire victims remain unpaid.

SCE has its own lengthy history of political scandals and cover-ups. Former Attorney General Kamala Harris appeared to look the other way for both power companies.

A report by ABC10 found that, of the 55 lawmakers representing California in Congress, all but nine have taken money from PG&E.

These power companies continue to raise rates on Californians while failing to maintain basic critical infrastructure in fire-prone areas or make their victims whole.

Ashes to ashes.

Butte County cattleman Dave Daley went viral among California ranchers when he wrote about what happened to his land in the 2020 Bear Fire:

I am enveloped by overwhelming sadness and grief, and then anger. I’m angry at everyone, and no one. Grieving for things lost that will never be the same. I wake myself weeping almost soundlessly. And, it is hard to stop.

I cry for the forest, the trees and streams, and the horrible deaths suffered by the wildlife and our cattle. The suffering was unimaginable. When you find groups of cows and their baby calves tumbled in a ravine trying to escape, burned almost beyond recognition, you try not to retch. You only pray death was swift.

Rural California has been suffering. Perhaps our urban neighbors thought it was safe to ignore us. If the cities thought our pain and devastation would stay isolated to the parts of California that don’t matter to Gavin Newsom, they know today it won’t. No place, not even Los Angeles, is so removed from nature.

There is nothing new about California’s dry climate or cyclical rainfall.

There’s nothing new about the devil winds.

Joan Didion wrote about them back in the ’60s:

It is hard for people who have not lived in Los Angeles to realize how radically the Santa Ana figures in the local imagination. The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself. Nathanael West perceived that, in The Day of the Locust, and at the time of the 1965 Watts riots what struck the imagination most indelibly were the fires. For days one could drive the Harbor Freeway and see the city on fire, just as we had always known it would be in the end. Los Angeles weather is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse, and, just as the reliably long and bitter winters of New England determine the way life is lived there, so the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The winds show us how close to the edge we are.

What is new are years of mismanagement, sprawling urban centers built in unattended dry brush, and underprepared government agencies focused on DEI and rhetoric over outcomes. This is the banal, boring brutality of bureaucracy. It’s death by a thousand cuts. This is why people ignore it, get numb to it, or finally move away.

This is why Los Angeles is burning.

A version of this essay ran on Keely Covello’s Substack and was republished by the Foundation for Economic Education.