Table of Contents

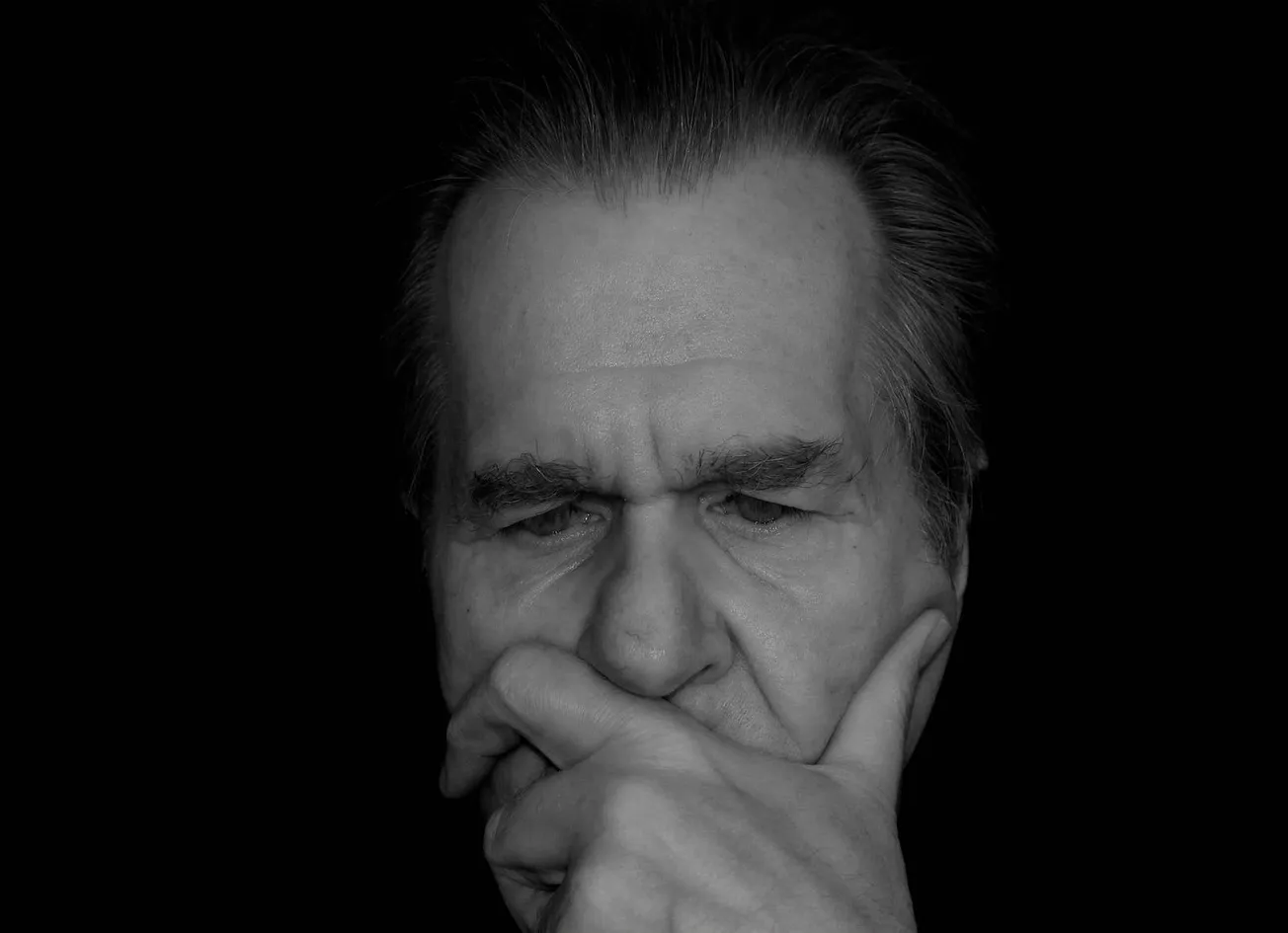

Don Brash

Don Brash was Reserve Bank Governor from 1988 to 2002, and National Party Leader from 2003 to 2006

A few weeks ago, Helen Clark and I wrote a joint op-ed for the New Zealand Herald entitled “We must not abandon our independent foreign policy”.

Since that time various people have ridiculed the notion that we could have a meaningfully independent foreign policy and there has been some enthusiasm for the discussions which our Foreign Minister, Winston Peters, has had first with his Australian counter-part, then with NATO and some individual NATO members in Europe, and finally in recent days with senior members of the Biden Administration in the United States. Media reports suggest that at a number of these meetings the possibility of New Zealand becoming associated with the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) defence agreement has been mooted.

Before any decision is taken to join any kind of military grouping, especially one so transparently aimed at our largest trading partner, there needs to be a great deal more discussion with the New Zealand public than we have seen to date.

There is no suggestion that AUKUS is anything other than a military partnership premised on the urgent need to push back against China.

And any New Zealand involvement would presumably also be premised on the need to defend the country against purported Chinese aggression.

Certainly, anybody knowing anything at all about Chinese history since 1839 should not be surprised if China were to be militarily assertive two centuries later.

Centuries before 1839, China was an advanced civilization. China is widely regarded as the country where paper, movable-type printing, gunpowder, and the compass were invented. In the 15th century, as Columbus was sailing the Atlantic, a Chinese fleet with vessels substantially larger than the Santa Maria sailed from China to the east coast of Africa – only to be destroyed on returning to China because the emperor decided that the rest of the world had nothing to offer China.

But starting in 1839 at the hands of Britain, China suffered serious military defeat by a succession of European Powers and was forced not only to concede territory to them but also to pay reparations for the damage which had been done to European interests in China – largely because the European Powers insisted on selling opium to Chinese merchants against the law. Chinese citizens were treated little better than animals, and in major cities were often banned from entering premises reserved for Europeans.

In 1894, Japan too attacked China and under the treaty which ended that war, gained substantial territory on the Chinese mainland and the island of Taiwan.

Humiliation continued into the 20th century. The European Powers which forced the Treaty of Versailles on Germany at the end of the First World War decided that the parts of China which had been occupied by Germany should be handed over to Japan. And, of course, a few decades later Japan invaded other parts of China and slaughtered an estimated 20 million people, many of them unarmed civilians.

So between 1839 and the middle of the 20th century, the country which had regarded itself, with some justification, as among the most advanced countries in the world was repeatedly humiliated by other Powers. It would therefore not be in the least surprising were China to want to restore its earlier status vis-a-vis the rest of the world, or at least with respect to those countries which had humiliated it.

Yet while there is abundant evidence that China is determined not to endure another century of humiliation, there is little evidence that it seeks retribution. Yes, China has greatly expanded its military forces over the last decade or two but, while estimates vary, it spends only about a third of what the US spends on its military. Apart from militarizing some very small “islands” in the South China Sea, China appears to have only a single overseas military base, in Djibouti.

By contrast, according to Google the US in 2023 had some 750 overseas military bases, some very small, but others accommodating thousands of troops, including bases all around China’s eastern border – in South Korea, Japan, Guam, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and Australia. The US insists on its right to sail naval vessels up and down China’s coast in a way which the US would not tolerate if the boot were on the other foot, with Chinese naval vessels cruising up and down the coast of California.

What we have is the classic situation described so admirably by Harvard professor Graham Allison in his book Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? Allison argues that when a dominant Power, such as the US, is confronted by a rising Power, such as China, war is almost always the result (or at least, was the result in 12 of the 16 cases Allison considered over the last 500 years).

The US has been the dominant Power for many years – arguably since the end of the First World War, but certainly unchallenged in that position since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. But now it is being challenged by a rising Power in the shape of China. China’s economy is already larger than the US economy (measured on the purchasing power parity exchange rate preferred by economists) and because of China’s enormous population – four times that of the US – China’s economy will be twice the size of the US economy if Chinese living standards reach even half those in the US.

Various writers have questioned whether New Zealand has the option of having the independent foreign policy we claim to have had over the last forty years. Surely, we should be allied with countries with “Western values”, a belief in individual freedom, and so on? That clearly implies an alliance with the US. But the emerging power struggle between the US and China is not about “Western values” but rather about an old-fashioned struggle for dominance. The US has long been allied with countries which are a very long way from being democracies (think Saudi Arabia and Egypt) and is now actively courting Vietnam.

We would also be wise to recall that over at least the last half-century, US military adventures have been disasters, both for the US and for the countries directly involved. The Vietnam War cost more than 58,000 US military deaths and an estimated 3.5 million Vietnamese casualties. The Iraq war was on a smaller scale in terms of loss of life, but hardly a success in any dimension, with Iraq now having an unstable government under the influence of Iran. The military occupation of Afghanistan was very costly for the US and its allies, was even more costly in terms of loss of life for the Afghans and, following US withdrawal, has left Afghanistan once again ruled by the Taliban.

At this point, the Prime Minister describes Australia as our only ally. But that should surely not imply that, just because some Australians want to buy into America’s desire to remain the dominant Power in East Asia, we should buy into that nonsense also. (And not all Australians are enthusiastic about AUKUS – both former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating and former Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull have raised serious concerns about AUKUS.)

To me, Singapore’s foreign policy provides a model worthy of study. Singapore appears to have a cordial relationship with both the US and China. In April 2022, Singapore’s Prime Minister formally stated that Singapore is not an ally of the US, would not conduct military operations on behalf of the US, and would not seek direct military support from the US. Why wouldn’t that work for New Zealand?