Table of Contents

Republished with Permission

Bryce Edwards

Political Analyst in Residence, Director of the Democracy Project, Victoria University of Wellington.

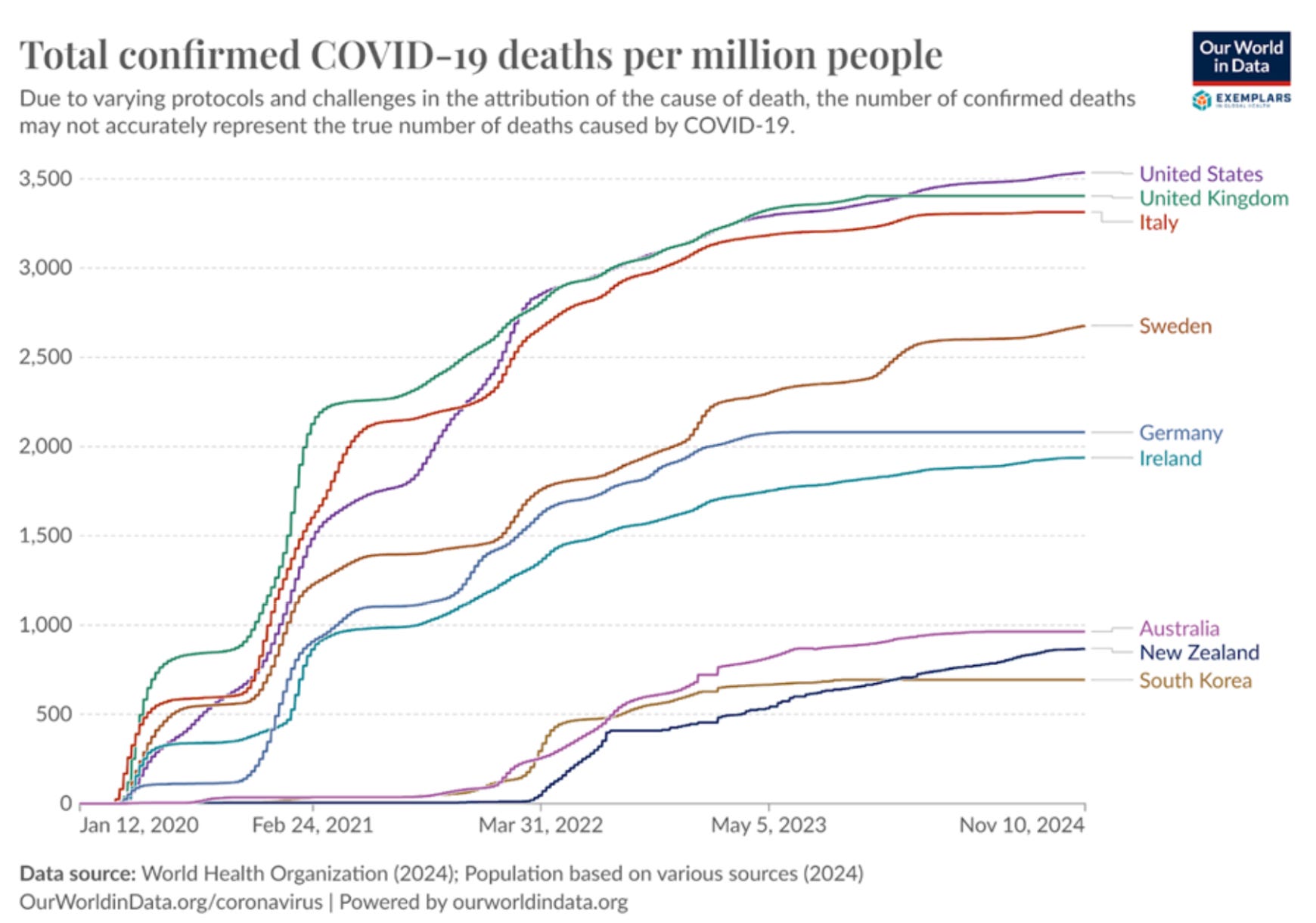

Any criticism of New Zealand’s Covid response needs to begin by acknowledging its success. Our total confirmed deaths per million people is far lower than those of many peer nations. But we’re still living with the cost of that response: reduced trust in institutions and deeper social division; years of inflation and years of recession.

Did we have to make those trade-offs, or could politicians have saved just as many lives without the downsides? Was there a change in the quality of decision-making between the earlier and later stages of the pandemic? The first phase of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Covid-19 Lessons Learned has just been released, and it casts light over some of these questions.

The Covid response was the most significant political event in New Zealand in a generation. The borders were closed; the government printed and borrowed enormous sums of money and infringed upon the rights of the entire population. The event warrants close examination, but the nature of the royal commission itself is controversial. Announced by Jacinda Ardern, its scope examined the overall pandemic response and recommended policy responses for future pandemics but was prohibited from examining the governments “individual decisions”, parliamentary proceedings or the operation of the Reserve Bank’s monetary committee, all of which should have been at the heart of a genuine enquiry.

Ardern also insisted upon keeping all hearings private – almost unheard of for a commission, especially one of such importance. She claimed it would “promote a non-adversarial atmosphere”.

Due to the change of government there will be a second phase of the royal commission of enquiry. This will examine “the use of multiple lockdowns, vaccine procurement, the socio-economic of the Covid-19 pandemic on regional and national levels, the cost-effectiveness of the government’s policies, the extent of disruption to public health, education and businesses caused by the government’s policies, and whether the government response was consistent with the rule of law.” The next phase of the commission will hold public hearings.

Key findings and recommendations

The conclusions will not come as a surprise to those who experienced the pandemic. The commission finds that the early elimination strategy was effective but there was no strategic planning about what to do if it failed, which it inevitably did.

Policy making was “a game of two halves”: decision making processes worked well during those early stages but deteriorated when they became overly centralised. Health outcomes were prioritised over economic and social impacts of the lockdowns. Communication during the early phase was effective but became less so over time: “The transition out of the elimination strategy was not well signalled or communicated... leading to an unsettling impact on people.” This opened the door for the misinformation that caused havoc in the later stages of the pandemic.

The over-reliance on lockdowns was driven by lack of proper public health infrastructure. The government’s response disproportionately impacted vulnerable populations, particularly Māori, Pacific communities, and lower-income groups. The Managed Isolation and Quarantine system (MIQ) seemed unnecessarily arbitrary and cruel: athletes, performers and other VIPs seemed to receive preferential treatment over families with young children, or people attempting to reach dying relatives. State agencies were bad at collaborating with NGOs, iwi, community organisations and each other.

The vaccine mandates were too broad, causing job losses, financial hardship and significant stress to individuals and families who did not comply. It found that “vaccine mandates wore away at what had initially been a united wall of public support for the pandemic response; along with the rising tide of misinformation and disinformation, this created social fissures that have not entirely been repaired,” and that “The case for vaccine requirements of all kinds weakened in early 2022 with the arrival of the Omicron variant, since vaccination was now much less effective in preventing Covid-19 transmission and immunity waned over time. While beneficial to the individual concerned, vaccination now offered less protection to others and the public health case for requiring it was weak... some workplace, occupational and other vaccine requirements were applied too broadly and remained in place for too long, which caused harm to individuals and families and contributed to loss of social capital.”

The non-negotiable nature of broad vaccine mandates were the focus of the anti-vaccination protests and the parliamentary occupation in early 2022. In an interview with Radio New Zealand, the head of the commission, Tony Blakely, said that a future mandate policy “has to be done very cautiously – even if the majority of the population are in the mood, in the drive, of the view that it should be happening – is that the unintended consequences or, some would say, perfectly anticipatable consequences for the minority are major – and they should be considered.”

Some of the key recommendations are sensible. Prepare for the next pandemic by stockpiling essential supplies, building surveillance systems to detect early outbreaks, redesign MIQ to make it less horrible.

Many are simply proforma, standard across every public report. Improve communication. Strengthen partnerships. Uphold the principles of Treaty of Waitangi.

As is also standard with royal commissions, the finding that stage agencies underperformed and worked in silos is supposed to be addressed by the creation of a new agency: a national pandemic preparedness and response agency, which will develop an all-of-government pandemic plan. But surely any new agencies will be run by senior managers from the existing bureaucracy, who will just replicate all the existing cultural and institutional problems.

The flood of money

In the economic and fiscal response, the pattern of early triumph undermined by poor decision making and lack of strategy repeats itself. In the early days of the lockdown the government moved quickly to roll out a suite of measures to prevent mass unemployment and a crippling economic depression as most of the nation’s businesses were forced to close. The wage subsidy scheme (costing $18 billion), Covid-19 grants and tax relief were delivered swiftly and seemed to function well. GDP returned to pre-Covid levels by the third quarter of 2020.

But the recovery was not evenly distributed. Businesses that were not impacted by the pandemic still qualified for the wage subsidy, at the same level as those that were seriously affected – particularly those that relied on international tourism. There were plenty of overpayments and claims by businesses that did not need the support, highlighting gaps in accountability and monitoring mechanisms. Future generations will be indebted by the $18 billion, much of which simply inflated the bank accounts of the wealthiest.

The overall economic response prevented a recession at the time, but the borrowing and stimulus spending led to the cost-of-living crisis, and the response to that has caused a sustained recession. It found that the pandemic exacerbated existing inequalities, particularly among lower-income households, Māori, and Pacific peoples.

Lessons learned?

The overall impression is of a government that performed well under crisis but failed to respond to changing circumstances or form coherent long-term strategies. These are the standard critiques of Ardern’s administration.

It’s notable that early stages of the pandemic were overseen by a coalition/confidence and supply government – Labour, New Zealand First and the Greens. This was then replaced by a majority Labour Government, and the quality of decision-making degraded. The case for MMP was that the very centralised nature of New Zealand’s Executive led to groupthink and overreach, and perhaps this argument has been validated by the pandemic.

The report has much to say about the issues of misinformation and public decline in institutions which it regards as misguided. But the other findings of the report suggest that many of those most impacted by the pandemic policies were correct in their mistrust of government, which prioritised the interests of property-owners and big business over those of minority groups and low-income households.

And the opaque and constrained nature of the commission itself suggests that mistrust is still warranted. Why would a government set such limited terms of reference if there was nothing to conceal? Perhaps this question will be answered in the second phase of the royal commission which is currently due to report in February of 2026.

This article was originally published on the author’s Substack.