Table of Contents

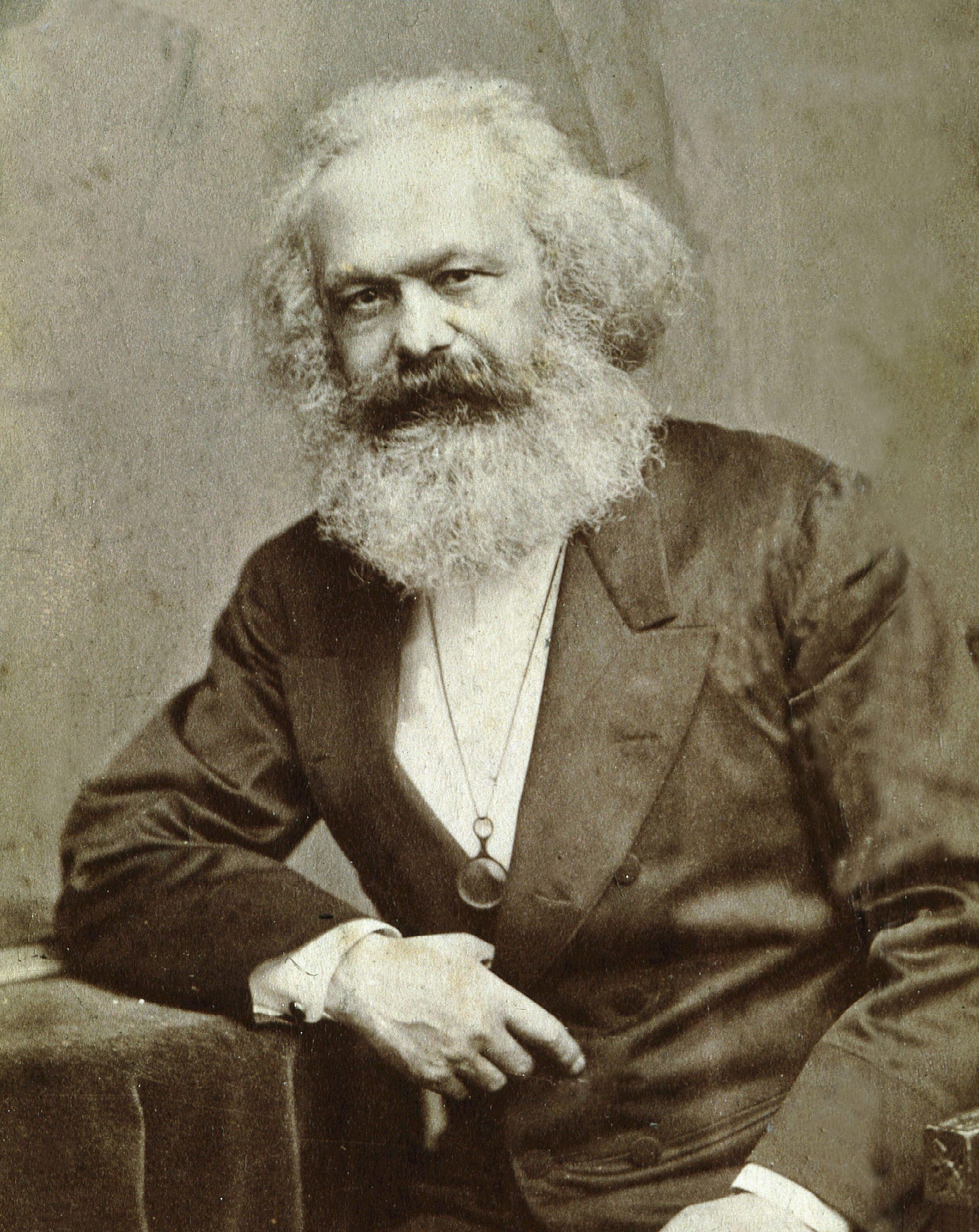

Depending on which side of the Marxist divide your sympathies lie, Karl Marx himself was either the devil incarnate or a luminous angel who was “beloved, revered and mourned by millions”.

The last sentiment, spoken at Marx’s funeral in 1883 by his lifelong friend and collaborator, Friedrich Engels, was certainly premature. It was not for another quarter-century at least that Marx’s ideas would become widely known and admired.

Opponents of Marxism, on the other hand, tend to view Marx as the monstrous wellspring of the evils of communism. While that may be true of his ideas, what of Marx the person? Does that even matter? Criticising Marx’s person in order to criticise his ideas, of course, runs the risk of the ad hominem fallacy. On the other hand, ideas don’t spring out of a vacuum, so the character of Marx might well be at least informative of Marxism.

At least one doctor, making a retrospective diagnosis of the skin diseases that afflicted Marx all his life, wondered whether the well-known psychological effects (loathing, disgust and depression of self-image, mood and well-being) affected Marx’s work and even helped him to develop his theory of alienation.

Indeed, when considering historical figures responsible for great, influential movements, it’s worth considering if those persons’ personal lives substantiate or undermine their ideology. As Aristotle noted: “Men start revolutionary changes for reasons connected with their private lives.” In Marx’s case, as Grove City College professor Paul Kengor recounts in his recent book “The Devil and Karl Marx,” the record is not in his favor.

Certainly, Marx was not entirely a “nice guy”. But then, many great people aren’t – entirely. Considering Marx’s life though, one cannot help but notice his lifelong irresponsibility as a son, husband and father, and consequent leech-like dependence on others for money. If nothing else, as Thomas Sowell notes, Marx and Engels were brilliant young men who never took responsibility for their lives – unsurprisingly, perhaps, they have appealed to similar types ever since.

He […] squandered his parents’ money, while remaining silent for months at a time, even when both his mother and father were ill. When Karl did write, it was typically to request more funds.

In one December 1837 letter to Karl, Heinrich reprimands his selfishness, writing, “You have caused your parents much vexation and little or no joy….” A few months later, Heinrich died at age 56. Karl did not attend the funeral. He had “other things to do,” one biographer explains.

Karl then turned to his mother for hand-outs. Even after getting married in 1843, he remained dependent on his mother to finance his intellectual career, draining his parents’ savings. Even so, he went nearly 20 years without visiting his mother, and when he finally did see her, it was for money […]

When his mother died, Karl was able to secure about $6,000 in gold and franks as inheritance. That, notes Kengor, is a bit rich, given that point three of the “Communist Manifesto” calls for abolishing the right of inheritance.

As Francis Wheen, as sympathetic a biographer as could be imagined concedes, the income Marx leeched off family and friends was certainly sufficient to have lived a comfortable, if modest middle-class existence. But, as his mother and wife both bemoaned, for all the time Marx spent writing about capital, he showed no interest in accumulating it.

Marx’s family life was a disaster. Four of his six children died before he did. The other two, both daughters, eventually committed suicide. His poor wife, who suffered through adultery and neglect, by the 1860s was expressing a desire to die. Marx once wrote to Engels: “Blessed is he who has no family.” Jenny died in 1881. Marx did not attend the funeral.

This is just trying too hard to blacken Marx’s name – by omission and by falsehood.

For instance, Marx was unable to attend his wife’s funeral due to his own illness. It is simply untrue that both his daughters committed suicide: his eldest, Jenny Longuet, died of cancer shortly after the death of her newborn daughter – and just two months before Marx’s own death. Laura Marx committed suicide in a pact with her husband, Paul Lafargue, in 1911, long after Marx’s death.

In fact, for all their difficulties (Jenny left Karl twice), the Marx family life seems genuinely affectionate and dedicated to their father, whom they nicknamed “Moor” (in reference to his dark complexion and wiry hair). For his part, Marx could be indulgent to a fault: much of the family’s money problems came from the fact that Marx frittered a great deal of his income attempting to keep up the lifestyle appearances of the upper-middle-classes. Holidays at seaside villas, piano, deportment and riding lessons for his daughters: these were what preocuppied Marx ahead of mundanities like the rent or the grocer’s bill.

It did not seem to dawn upon Marx that he was most to blame for their poverty and misfortune.

At one point a servant girl, Helene Demuth, who had been a housemaid for his wife’s family was sent to help the Marx family while they were living in Brussels in 1845. Marx never paid Demuth a penny. He did, however, initiate a long-running extramarital affair with her.

In June 1851, Demuth gave birth to a baby boy, Freddy. Marx refused to acknowledge that the child was his.

Marx, despite his own Jewishness, was often virulently anti-Semitic. His correspondence, biographers have noted, is “filled with contemptuous remarks about Jews”. Not just Jews: Marx’s opinions about blacks and homosexuals were far from flattering.

Why does this matter? For people to subscribe to certain political ideologies, especially those as sweeping in scope as Marxism, they should be aware of the motivations and lives of those they aim to follow. In the case of Marx, those motivations were arrestingly selfish. His life is a case study in how to mistreat everyone close to you.

This is supposed to be the person who proposed how to free the oppressive masses from their social and economic bondage? As Kengor notes, Marx knew practically no members of the proletariat, and those he did know, he viewed with disdain, or, in the case of his servant mistress, as people to be exploited.

The Federalist

Those last points are probably the most salient as regards Marx the man versus Marxism the philosophy.

More importantly, Marx was frankly a bully. Much of the reason his great work Capital remained unfinished was that Marx wasted so much time and energy arguing and attacking his enemies, real and imagined. In debate, he was apt to resort to shouting, “I will destroy you!” His written work is likewise peppered with similarly violent language.

And that sounds a lot more like Marxism as it has been lived by those forced to suffer under its yoke.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD