Table of Contents

As Geoffrey Blainey argues in A Short History of Christianity, far from being a fictional character, the very fact that we know anything at all about Jesus is remarkable in itself. After all, a middle-class Jewish carpenter’s son in a far-flung boondock province was the last sort of person the Roman Empire was interested in recording for posterity. Mostly, the empire was concerned with the doings of the people it thought mattered: emperors, generals and, of course, the Roman officials who kept the whole place running.

One such official is a name who’ll be instantly recognised by many people, in even a secular age as our own: Pontius Pilate.

Pilate is, of course, the Roman official who presided over the trial of Jesus. But who and what was he, exactly? Like so many people of then-minor importance, he is shrouded in mystery.

What we do know is that Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judea, for some 10 years. Years that coincided with the ministry of a wandering Jewish prophet named Yeshua ben Joseph. Like Yeshua – or Jesus – Pilate probably rose from the middling classes of his own society to become a world name.

Little is known of Pilate’s life before the fateful years of the early first century. It’s believed that he was born in Italy and came from a family of equites. These ‘equestrians’ were an order of Patricians below the Senatorial class. Usually translated as ‘knights’, one modern history preferred to call them by the somewhat clunky, “Roman gentlemen outside the Senate.” His family were undoubtedly wealthy.

Probably originally a distinguished military man (Pilatus means armed with a javelin), Pilate was appointed a prefect: a high-ranking role, even in a backwater province. A prefect supervised the province’s finances and military, and acted as chief justice and head of the civil service.

In Judea, Pilate would have worked closely with the Jewish elite, the Sanhedrin. The relationship was not an easy one. Although the Romans were, by the standards of the time, remarkably tolerant rulers, they did have a few hard rules: pay Rome’s taxes and pay (lip service at least) to the official Roman gods. Which is where much of the conflict in the region began.

As Flavius Josephus, a Jew who first fought then sided with the Romans, records, Pilate first upset Jews by placing busts of Caesar in Jerusalem: an edict which violated Jewish prescriptions on graven images. This sparked days of rioting, which only calmed when Pilate backed down and removed the offending images. Taxing temple funds caused more riots – and a brutal crackdown.

But all this would have faded into the history books, were it not for the momentous turn in world history that he was dragged into: the trial and crucifixion of Jesus.

According to the Gospel, the Sanhedrin had Jesus arrested because they felt threatened by his teachings, alleging he claimed be the “King of the Jews”, which would have been considered both blasphemy and treason.

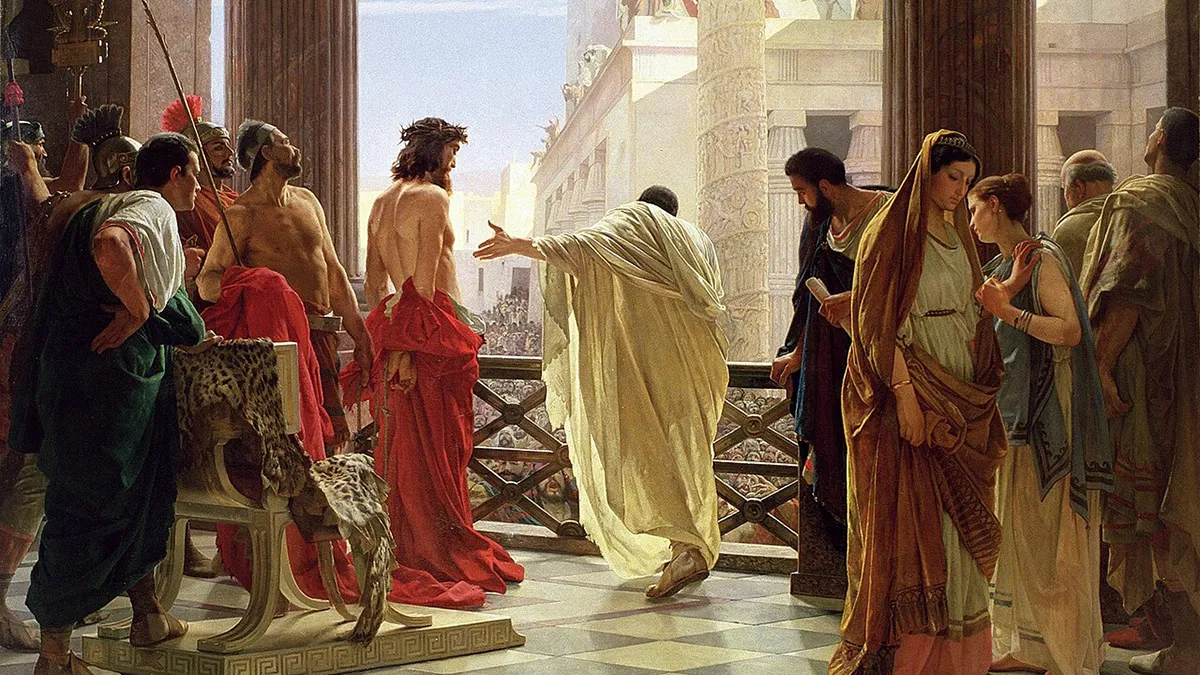

Soldiers took Jesus to Pontius Pilate for judgment, but Pilate was reluctant to convict him. The Gospels depict Pilate as being conflicted and indecisive in contemplating Jesus’ fate […]

Not seeing any legal grounds to sentence Jesus to death, Pilate attempted to defer the responsibility, telling the Jewish elders, “Take him yourselves and judge him by your own law.” But they refused. After all, Pilate was the only one with the authority to order the death penalty, and they wanted Jesus executed.

According to the New Testament, worn down by their insistence, Pilate eventually gave in to the demands of the Jewish authorities and ordered that Jesus be crucified. It’s said that at that point, Pilate literally washed his hands before the Jewish council, denying his responsibility and instead blaming the Jews.

All That’s Interesting

These gospel accounts were written at a time when the new Christian religion was no doubt anxious to assure Rome, which heavily persecuted them, that it was not a threat. So it is possible that they deliberately downplayed Pilate’s responsibility. Whatever the truth, they were to inadvertently (being written by Jewish writers) bring dire repercussions to the Jews of Europe for millennia.

As for Pilate himself?

If the Letters of Herod and Pilate are to believed, Pilate repented of his role in Jesus’ crufixion and indeed converted to Christianity. The reliability of these letters is disputed, of course. Other records attest that he lost his position after Samaritans complained to the Roman governor of Syria, Vitellius. Pilate, they said, had massacred a group of Samaritan pilgrims. Vitellius recalled Pilate to Rome, to answer to the emperor.

And that’s where the records end. Some suggest that Pilate was executed by Caligula, or was exiled and suicided. Certainly, he never returned to Judea.

But he did end up in the history books.