Table of Contents

Chris Penk

First published by The BFD 19th June 2020

The BFD is serialising National MP Chris Penk’s book Flattening the Country by publishing an extract every day.

Winners picked and losers packed

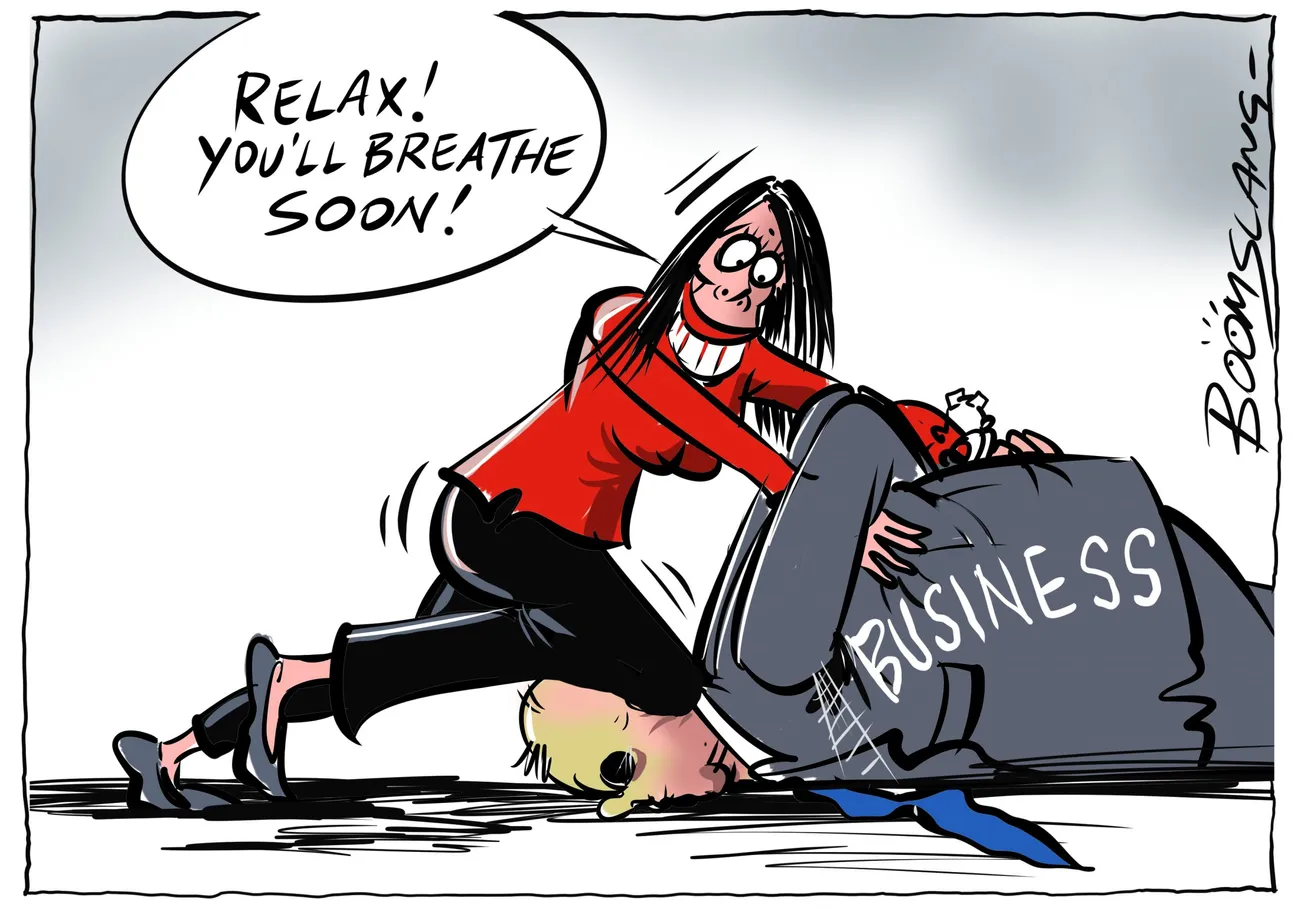

The economic response to the COVID-19 threat was a mixed bag from the start. In mid-March, the Minister of Finance announced support for business that was not really any such thing.

It was positive that the government allowed for a wage subsidy to enable employees to be retained by businesses but this was hardly a measure of support for businesses themselves, given that the subsidy had to be passed on.

Incidentally, the wage subsidy wasn’t even as generous as it appeared from the perspective of employees. As Wolters Kluwer NZ pointed out:

The tax treatment for the employee is as follows: the payment is taxable remuneration and subject to PAYE, ACC levies, KiwiSaver contributions and student loan repayments at the date of payment.

But a bigger problem was blindingly obvious to all but Beehive bumblers.

Numerous non-wage costs still needed to be met by businesses and the cavalry was taking its sweet time to arrive, as weeks went by without anything more to go on than vaguely encouraging noises.

To rub salt into the wound, the government proceeded with its planned increase to the minimum wage, despite it being abundantly clear that this could be the last straw upon the backs of Kiwi businesses. Effective from the morning of 1 April 2020, this unwelcome rise must have seemed to many a pretty cruel trick.

Businesses realised that they would struggle to increase their wage bills while revenue plummeted. Wise workers knew that the bird in the hand of current employment was worth much more than a slightly higher wage that might prove elusive.

When the ship goes down, her crew as well as her captain go down.

Eventually the government did offer more than the original wage subsidy but only the prospect of loans that would attract interest after an initial period.

As my colleague Todd McClay put it, “small businesses need cash flow not cheap debt”.

For the thousands of businesses that had been starved of revenue for the last six weeks, he said, that announcement was “too little and [risked] being too late”.

The point about cashflow was that it was well within the power of Ardern and Robertson to give businesses the one thing that they needed above all else: the ability to trade their way out of trouble.

“Every business that stays open means more jobs are kept”, McClay noted, but Labour’s leadership continued to respond with virtue-signalling vacuity. Rather than taking a sensible approach to allowing commerce on condition of safety measures being maintained, Ardern’s position again and again was: let’s not do this.

What are you waiting (Level) 4?

Again and again the National Party, along with some sensible others, made the point that it was a matter of desperate urgency that the country return to some version of normal.

The autocratic absurdity that was Alert Level 4 should not have persisted nearly as long as it did.

An opinion editorial by our finance spokesperson, Paul Goldsmith (entitled “The opportunity now is to prepare so that New Zealand can succeed in the post-Covid world”) made this point clearly:

The first priority is getting out of lockdown as soon as we safely can. I’m worried by the apparent lack of appreciation amongst some government MPs of the seriousness of economic calamity facing many businesses. The damage has been masked in the short term by 1.6 million Kiwis receiving the wage subsidy. Many otherwise strong businesses will not survive zero revenue for at least 7 weeks.

A former National Party spokesperson named Sir John Key (also a former MP for Helensville, I might add) would make a substantially similar point later on, regarding the need to move from Level 3 to Level 2:

I don’t think the Government should wake up every day and say are we in level 3 and I’ll let you know in a couple of weeks if we move to level 2. I think they should get up every single morning and say what could we do, how could we get the economy growing faster, how could we get people back into work and into their businesses and do that in a safe way.

That interview by Paul Henry contained one rather chilling insight from Key, a lesson learned in the aftermath of the 2011 Christchurch earthquake: simply put, “the longer a business is out of action, the less likely it’s coming back”.

In the case of both impending transitions – from Level 4 to Level 3 and then from Level 3 to Level 2 – the government was affording to Kiwis far too little notice.

Ahead of the originally scheduled end to Level 4’s restrictions, Prime Minister Ardern advised the timeframe for Cabinet making a decision about whether or not the lockdown would be extended.

It is my intention that on the 20th of April, two days before the lockdown is due to finish, Cabinet will make a decision on our next steps. That’s because we need to use the most up to date data that we have to make that decision.

That’s right, businesses were to be given just two days to get up and running again from a sedentary position. Or not.

The uncertainty of not knowing whether they’d be allowed to turn on the tap was as great a problem as the length of the lockdown.

Ardern blithely stated that businesses should prepare for Level 3 to come into effect at the expected time, whether or not that would prove to be the case: “In the meantime I ask every business to use the time you have to prepare for what every alert level may mean for you”.

Many businesses were baffled that the Prime Minister, and fellow ministers presumably, did not realise that one cannot simply prepare to re-open at two days’ notice, on the off-chance that one may be allowed to do so.

Would food outlets order perishable supplies in advance, merely hoping that they would be able to be used? As it happened, the Level 4 lockdown was extended by five days, so goodness knows how much food ended up wasted as a result. Plenty of perfectly edible food had already been left to rot at the start of the Level 4 lockdown, as you might recall. During a mad moment in which bureaucracy trumped democracy, greengrocers and butchers were deemed non-essential and outlawed even from giving away their wares. But more on that later.

Ardern’s rationale for providing so little notice was that the most up-to-date information was needed for the decisions to be made. Cabinet could easily have met a couple of days prior to its scheduled meeting and made its decision on the data available at that time.

A decision point one week prior to the scheduled end of the lockdown would have allowed three weeks’ worth of data to be used, in the context of a disease that manifests within two weeks.

Interestingly, the period of two weeks – consistently cited by the Director-General of Health as the relevant one to establish infection – was the initial period scheduled for the Level 3 lockdown. In the eyes of the authorities, two weeks must be a sufficient period of time to gauge the effectiveness of a lockdown regime, so three weeks should have sufficed in mid-April.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.

Sources:

- COVID-19 wage subsidy:tax consequences

- national.org.nz/small_businesses_need_cash_flow_not_cheap_debt

- stuff.co.nz/business/121249170/paul-godsmith-getting-new-zealand-working-again-heres-my-plan

- newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2020/04/coronavirus-sir-john-key-calls-on-government-to-open-the-economy-more-while-in-lockdown.html

- stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120936873/coronavirus-decision-to-exit-lockdown-or-not-will-be-made-on-april-20