Table of Contents

Francis Phillips

mercatornet.com

Churchill & Son

By Josh Ireland. 2021. 464 pages

When you read of domestic conflicts on a large and violent scale, you go back to the Greeks: Agamemnon’s unhappy family and the fated House of Atreus. The Churchills inhabited a similar world, full of sound, sadness and fury, shown here in all its dramatic stages.

Josh Ireland does not provide new material in this study of Winston Churchill and his relationship with his only son, Randolph, but he relates it with even-handed sympathy for both chief actors. The reader is drawn in, spell-bound at the spectacle and its tragic trajectory.

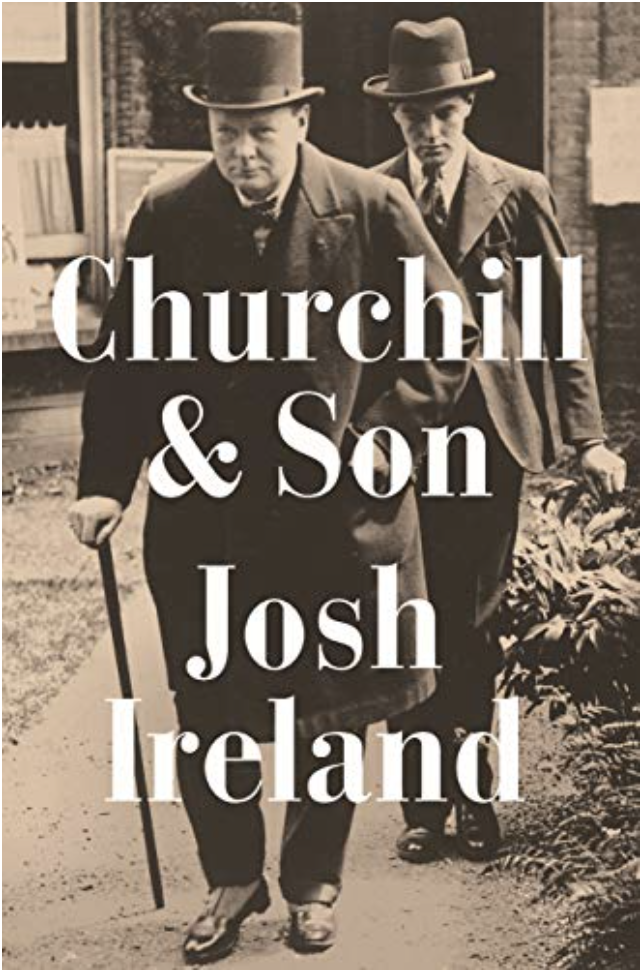

The front cover photo, taken in 1930, shows Churchill with his familiar expression of bullish determination and defiance, grasping a stick as he walks ahead of his son, then aged 19, closely following in his father’s footsteps. This was Randolph’s insoluble, lifelong problem: how to function successfully, independent of the overwhelming aura cast by his father.

Ireland rightly begins with Churchill’s parents, particularly his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, younger son of the Duke of Marlborough, for the seeds of Winston’s approach to raising his own son were sown in his own childhood and youth. Even in an aristocratic age of parental detachment from their children, Lord Randolph’s treatment of his son stands out for its coldness and cruelty. Winston worshipped him, only to be met by constant criticism and rebuffs. Quoting from the letters the lively boy sent his father from boarding school, begging him to visit, Ireland comments, “What is hardest to read in these letters, is not Winston’s palpable hurt, but his attempts to explain his pain away.”

Lord Randolph died of suspected syphilis in 1895 when his son, born in 1874, was aged 21, the gulf between them unbridged.

His father’s memory dominated the aspiring politician. When Winston himself went into Parliament, he imitated his father’s mannerisms, learnt his father’s speeches by heart and furnished his rooms with his father’s effects. Along with his urgent sense of purpose – “he lived life at a different pitch from most people” – his belief in his destiny and his fear that he, like his father, would die young, Winston was utterly resolved to show his own son the fatherly love that he had been denied.

Randolph, born in 1911, began life burdened with expectations: to live up to his dynastic inheritance and to shine in Parliament as his father and grandfather had done. “Randolph will carry on the lamp”, Churchill wrote to his wife in 1915, when his son was only four.

Even if he had been endowed with more talent than he possessed – he had an excellent memory, a quick intelligence and an ability to speak fluently on his feet with little preparation – Randolph conspicuously lacked Churchill’s own gift for prose, his formidable powers of concentration, his self-discipline and his limitless energy. From a young age, when he would recite to his father’s guests at dinner, leading to his joining their company, their conversation and their drinking in his teens,

Randolph was regularly indulged by Winston in his determination to compensate for his own childhood neglect; in Shakespeare’s phrase he loved not wisely but too well. Randolph, flattered, spoilt, adored by his father and adoring him in return, was ruined. His younger sister Mary later observed, “The greatest misfortune in Randolph’s life is that he is Papa’s son.”

Unlike the young Winston, left to the wise and loving care of his beloved nanny, Mrs Everest (he kept her portrait in his room until his death), Randolph terrorised his hapless governesses with his wilful disobedience. At prep school when he got into fights his father was proud of him. Significantly, he chose to go on to Eton, not Harrow, his father’s old school, because “there were fewer rules and much less discipline.”

When his mother Clementine, herself almost completely wrapped up in her husband’s political career, attempted to remonstrate with Winston over his behaviour, he overruled her; his love for his son would brook no criticism of what was becoming painfully obvious to others who watched as Randolph grew up: his rudeness, his lack of intellectual discipline, his extravagant lifestyle, his gambling, his womanising and his heavy drinking. His bad behaviour, especially when drunk, was notorious. As Mary observed, “Randolph would pick an argument with a chair.”

Much as Churchill loved and needed his wife, it could be argued that the most significant relationship of his life was with his son; and when Randolph himself died in middle age in 1967, only two years after his father, a friend Laura Charteris commented, “Winston was the only person Randolph truly loved.”

Churchill’s possessiveness inevitably affected the relationship between mother and son. Clementine, unable to bear her son’s unkind treatment of Winston after drinking, when all his bitterness and frustration at the failure of his own life would come to the surface, would retreat to her room to avoid him. Randolph told his friends, “My mother hates me.”

Until Winston’s old age, when his sons-in-law, Christopher Soames and Duncan Sandys began to provide more congenial company than Randolph, who always brought financial chaos and emotional turbulence in his wake, father and son would communicate by phone or letter on a near-daily basis when apart.

In the early years, before Randolph’s promise had finally led to failure and disillusionment, they would spend hours in conversation deep into the night, discussing warfare, history, historical personalities and above all politics. Indeed, Randolph once wrote that he learned more from his father’s conversation than he ever did at school.

Ireland writes that Churchill “made it relentlessly clear to his son that success in the political arena was the only success that counted in life. A career spent outside the Cabinet was not worth anything.”

The father had dangled a tantalisingly glorious future in front of his son; yet the sad truth was that Randolph lacked the character, resolve and ability to achieve it. In 1947, aged 36, having lost his parliamentary seat and beginning to sense that his political career might be over before it had properly begun, Randolph remarked forlornly, “I always expected that political life would suddenly open up for me.” Having been surrounded from a young age by his father’s friends at the peak of their powers and their careers, he seemed unable to grasp the rigorous discipline and hard work such a life entailed.

Lord Londonderry once wrote to Churchill, “Randolph is so like you and yet so unlike you; like you in your enterprise and courage and forcefulness, and unlike you because he does not seem to recognise what you always recognise: that knowledge is the secret of power.” In his youth, determined to educate himself for his future destiny, Churchill had studied great writers such as Gibbon for hours at a time; Randolph, who left Eton early and dropped out of Oxford, found the world of popular journalism an easier, more attractive proposition than dogged intellectual effort.

Ireland’s book is engrossing: two men, one a famous father and the other a son dazzled by what he felt was his birthright, indissolubly bound together by ties of blood and devotion, yet unable to prevent the personal tragedy that followed in their wake.

On the one hand Winston “knew he had played his part in creating [Randolph’s] extravagant flaws…but he could not let his fantasy go.” On the other, only Randolph’s most loyal and long-suffering friends were able to glimpse, behind the belligerent bully, “the affectionate, impulsive, innocent boy that they had first come to love.”

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD.