Table of Contents

Animals have long featured in philosophical discussion. Xenophones wrote that, if horses or oxen could draw, they would draw their gods as horses or oxen. Plato likened humans to cattle: fit only to be slaves. Thomas Nagel explored consciousness by asking, “What is it like to be a bat?” More recently, Mark Rowlands wrote The Philosopher and the Wolf.

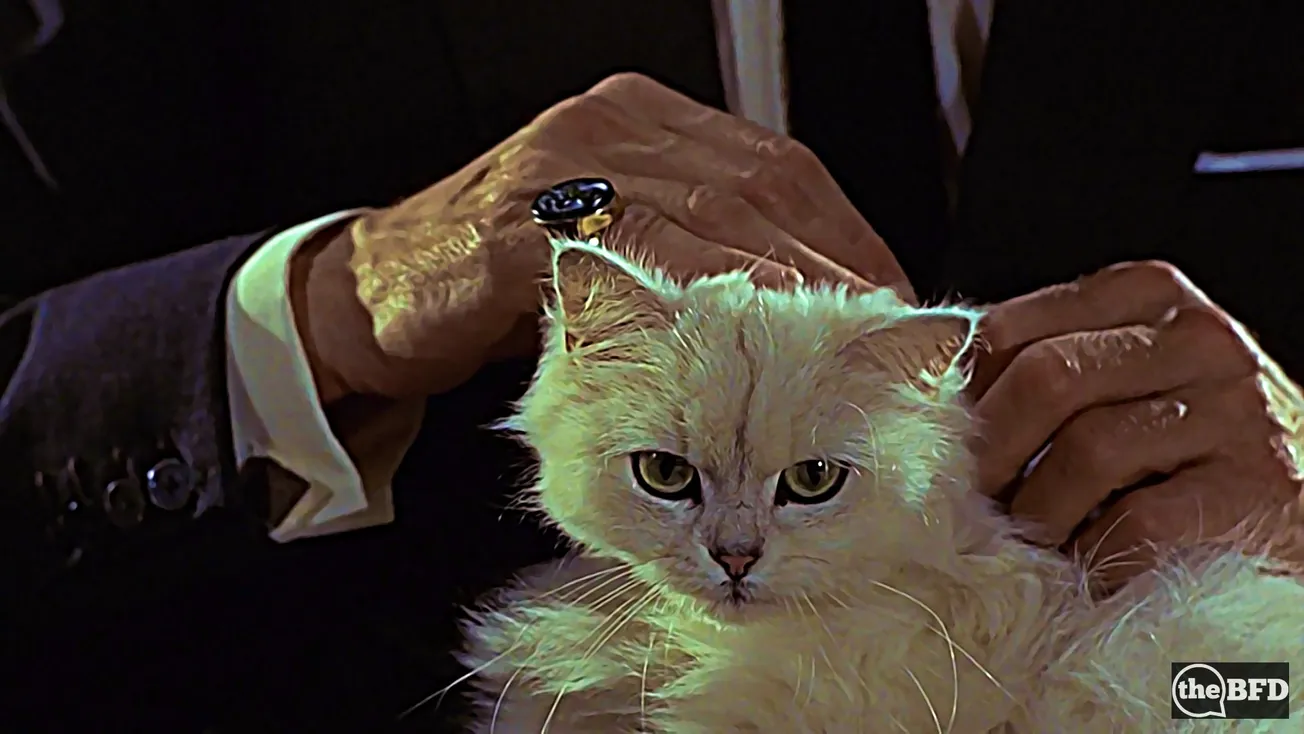

Now, John Gray is claiming that cats are the world’s “most profound teachers”.

In Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life, Gray writes,

“Humans cannot become cats. Yet if they set aside any notion of being superior beings, they may come to understand how cats can thrive without anxiously inquiring how to live.”

Yes, well… a flatworm or a jellyfish can likewise thrive without wondering much about the meaning of life. That doesn’t make them particularly profound thinkers, or indeed, thinkers at all.

Like a great many porch atheists, Gray really wants to argue, not the uniqueness of cats, but the valuelessness of humans.

Referencing Lao Tzu’s straw dog commentary on the basic irrelevance of humans – at best, we’re not special – Gray writes,

“The universe has no favourites, and the human animal is not its goal. A purposeless process of endless change, the universe has no goal.”

No, the universe has no favourites, but Gray is very wrong when he claims that humans aren’t special.

Cats, like humans and all other animals, do have goals: food, sex, shelter. Certainly not existential distress.

“Existential distress” is, in fact, the first hint that humans are indeed very special.

Humans are not designed to understand the complexities of the universe, nor even of our own biology. Even the notion of morality, as often marketed by religious traditions, is a farce, since people are only really “expressing their emotions”. The only recourse we have for discussing emotions – physiological changes that disrupt homeostasis and warrant explanation – is language, and language is a powerful but limited mechanism for discussing reality.

No one seriously argues, from a biological point of view, that humans are “designed” to do anything. But we have evolved in a very peculiar and, so far as we know, unique way. Unless flying saucers arrive to prove otherwise, humans are the only beings in the universe capable of existential distress. We are, as Pascal said, “only a reed”. But what a reed we are! Because we are “a thinking reed”. If the entire universe were to crush us, we would be nobler, because we know that we are dying. “The universe knows none of this.”

Nor do cats, however much we may love them. Whatever intelligence they may display (or, at least, appear to).

Despite what we believe, other animals don’t aim to become more human-like, nor did evolution finalize its process with us. Other species have little problem becoming what they are. That’s a uniquely human deficiency.

Uniquely human, yes. “Deficiency”? Hardly.

Only humans invent stories that reflect reality not whatsoever. Our brains chronically fill in knowledge gaps; those gaps often offer incorrect assessments. Existence is conditional to our environment regardless of how we try to manipulate it in our favor. You can only exploit nature for so long before she grows bored or angered by our tinkering – but there we go assigning human traits to a process that will never play by our rules.

This the cat knows – by not knowing, or caring, at all.

The cat does not know. Not because it chooses not to know, but because it cannot know. “Only humans invent stories.” “Uniquely human.” Again and again, Gray’s own arguments only serve to emphasise the singularity of humans.

“If cats could understand the human search for meaning, they would purr with delight at its absurdity. Life as the cat they happen to be is meaning enough for them. Humans, on the other hand, cannot help looking for meaning beyond their lives.”

Big Think

But they can’t understand the human search for meaning: that’s the whole point.

And Gray can no more conclude what cats would think any more than Nagle could know what it is like to be a bat. The only way to really know that, Nagle realised, was to be a bat. But a bat is incapable of wondering what it is like to be anything.

Only humans are capable of such higher-order thinking.

And that’s what makes us very, very special indeed.

But I still like cats, anyway.