Table of Contents

It may come as a surprise to you, but no one has ever actually seen an atom. That’s because individual atoms are smaller than the wavelength of visible light. So, how do we get those neat images of atoms? By inference: what we are seeing are in fact images compiled by using things such as a beam of electrons – much smaller than atoms – which are then ‘translated’ into pictures.

Similarly, for all the hoo-hah over exoplanets – that is, planets outside our own solar system – no astronomer has ever seen one.

Until now.

For the first time ever, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has imaged an exoplanet.

But wait, you ask: what about all those exoplanets we’ve been hearing about for years? Those were also detected by inference, most commonly by looking for irregularities in a star’s rotation. Just as the Moon’s gravity affects the Earth, most notably by causing tides, planets affect the stars they orbit, causing the star to ‘wobble’. By measuring the wobble, astronomers are able to determine the planet’s mass and its distance from its star.

Watching for transits is another method: just like an eclipse of the Sun, when an exoplanet crosses the face of its star, it causes its brightness to dim slightly.

But actually seeing an exoplanet? That’s a whole ’nother ball game.

Spotting a planet outside our solar system is like trying to photograph a firefly next to a searchlight – from a continent away. Stars are overwhelmingly bright, and planets are comparatively dim […]

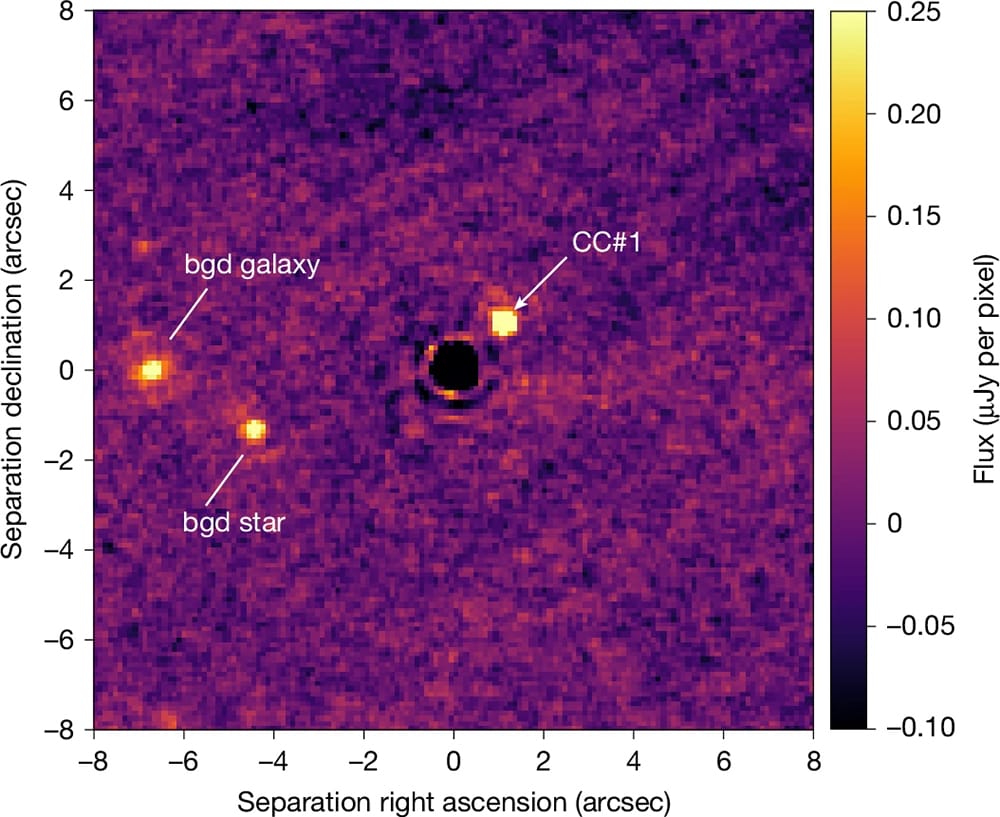

The discovery of TWA 7b is different because it was made using direct imaging with the James Webb Space Telescope. We have an actual photo of the planet itself (although you can’t really tell much about it) […]

To see the planet, the team used a special device called a coronagraph, built in France and installed on JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). A coronagraph acts like an artificial eclipse – blocking the blinding starlight so that dimmer objects nearby, like planets, can come into view. This technique had been used before on ground-based telescopes and even older space telescopes, but JWST’s powerful optics and infrared sensitivity make it much more powerful than its predecessors.

So, what do we know about this exoplanet with the unassuming name of “TWA 7b” (which sounds more like a domestic flight to Hoboken than another planet)?

The planet, called TWA 7b, lies 110 light-years from Earth. It’s roughly the mass of Saturn, orbiting a young star still surrounded by a hazy disk of dust and rocky debris. That dusty ring system helped scientists find their mark.

In other words, this is a solar system that is just getting its act together. Imagine our own Solar System roughly four billion years ago.

The star in the solar system, called TWA 7, is just 6.4 million years old – practically a newborn by cosmic standards. Its planets must be even younger, and young planets tend to be hotter and brighter in the infrared, making them easier to detect.

Earlier observations had shown that TWA 7’s disk contained three distinct rings of debris. These rings hinted at the presence of hidden planets, and now researchers have confirmed one such planet.

The planet orbits 52 astronomical units from its star. An AU is the distance from the Sun to the Earth. That’s a long way out: for comparison, Pluto is just 40 AU from our Sun.

That gives it a very slow orbit, possibly taking several hundred Earth years to complete one trip around TWA 7.

It’s also located right inside a narrow dust ring, nestled between two almost-empty zones. Simulations confirmed that a planet with TWA 7b’s properties could sculpt such a ring – explaining the sharp features that had puzzled astronomers for years.

So, what’s the big deal about directly imaging an exoplanet, if we could know so much about the hundreds of others so far discovered, by other means?

Although it’s harder to do in practice, direct imaging has distinct advantages. It allows scientists to study the planets’ atmospheres and compositions more precisely. And because the planet is young, it may help researchers understand how gas giants form and evolve.

Perhaps most importantly, it’s a step toward the ultimate goal: directly imaging Earth-sized planets in the habitable zones of nearby stars. That goal remains distant – but with tools like JWST and the next generation of telescopes, it’s no longer a fantasy. This single, faint dot in the dust, is a key milestone on that journey. The JWST is just getting started.

Of course, all that knowledge about exoplanets is fairly abstract, right now. Although it does at least give SF writers rich material, given how weird some of the exoplanets have turned out to be. Like the planet where it rains molten glass – sideways.