Table of Contents

When it comes to the weather, a change is as good as a holiday. One winter some years back, here in Tasmania, we had several months of continual rain, with only a handful of rain-free days. It was maddening. At the other end of the scale, friends who’ve lived in the tropical north said that the unending hot weather was a welcome change… for the first month or two. After a few months, they were itching to get back to Melbourne’s famous four-seasons-in-a-day weather.

But if mere months of rain were enough to drive me mad, spare a thought for the precursors of the earliest dinosaurs, who lived through what is known as the Carnian Pluvial Event. Or, to put it slightly more colourfully: 2 million years of rain.

If you hate the humidity, this would not have been the time for you: the seas were the temperature of hot soup and a global series of cataclysmic eruptions pumped massive amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Evaporation from the vast seas of the period eventually made landfall on the single continent of the era: the supercontinent Pangaea. When it did so, it naturally cooled – and fell as massive monsoons. Two million years of them.

But there’s another persistent weather pattern on Earth that we’re still living through: the persistent westerly winds that have turned most of central Asia to desert. It turns out that they’ve been blowing for a whopping 42 million years.

A University of Washington geologist led a team that has discovered a surprising resilience to one of the world’s dominant weather systems. The finding could help long-term climate forecasts, since it suggests these winds are likely to persist through radical climate shifts. “So far, the most common way we had to reconstruct past wind patterns was using climate simulations, which are less accurate when you go far back in Earth’s history,” said Alexis Licht, a UW assistant professor of Earth and space sciences who is lead author of the paper published in August in Nature Communications. “Our study is one of the first to provide geological constraints on the wind patterns in deep time.”

Previous studies, using rocks from the Loess Plateau in north-western China, showed dust accumulation associated with strong, persistent winds, beginning 25 to 22 million years ago. These increased over time, particularly the last three million years. Later research, using rocks from north-eastern Tibet, pushed the rise of the winds to more than 40 million years ago.

The new paper traces the origin of this central Asian dust using samples from the area around Xining, the largest city at the northeastern corner of the Tibetan Plateau. Chemical analyses show that the dust came from areas in western China and along the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, like today, and was carried by the same westerly winds.

“The origin of the dust hasn’t changed for the last 42 million years,” Licht said.

The winds have persistent through tens of millions of years of climate and tectonic, even Earth orbital, change.

During the Eocene, the Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan Mountains were much lower, temperatures were hot, new mammal species were rapidly emerging, and Earth’s atmosphere contained three to four times more carbon dioxide than it does today.

“Neither Tibetan uplift nor the decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration since the Eocene seem to have changed the atmospheric pattern in central Asia,” Licht said. “Wind patterns are influenced by changes in the Earth’s orbit over tens or hundreds of thousands of years, but over millions of years these wind patterns are very resilient.”

Oh, you just know there’s some climate alarmism coming.

The study could help predict how climates and ecosystems might shift in the future.

“If we want to have an idea of the Earth’s climate in 100 or 200 years, the Eocene is one of the best analogs, because it’s the last period when we had very high atmospheric carbon dioxide,” Licht said.

Science News

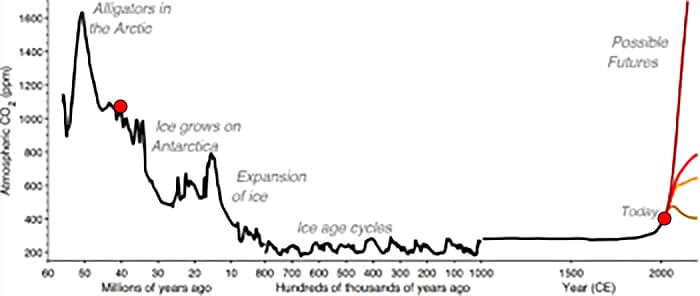

In fact, as this graph shows, we’re nowhere near the high levels of atmospheric CO2 experienced the Eocene. And almost certain not to get there in the next century or two. Of the “possible futures” shown in that graph, the only one projecting such high levels is the most extreme – and even by the IPCC’s reckoning, highly unlikely – scenario.

Can’t anyone just do science any more, without having to bow to the Climate Cult?