Table of Contents

For a while there, some scientists thought we were about to lose Betelgeuse.

Betelgeuse is an easy star to find in the Southern hemisphere summer: it’s the bright red star directly below the base of the “saucepan” (Orion). It’s one of the closest red supergiant stars to Earth.

And it had astronomers worried. As a red supergiant, Betelgeuse will go supernova… some day. One of the signs that this might be about to occur is if the star suddenly and drastically loses its brightness. A Betelgeusian supernova would be a dramatic and spectacular sight so (relatively) close to Earth. It would be as bright as a half-moon, at least for a few months – before fading away forever.

But, at 724 light years away, the enormous burst of radiation would have little physical effect on Earth.

Still, we stargazers (professional and amateur) would miss Betelgeuse when it was gone.

When it dramatically dimmed last year, many astronomers were convinced that this was a prelude to a supernova event. Luckily, perhaps, it turns out not to be so.

Betelgeuse, which is located roughly 724 light-years away in the constellation of Orion, is the second-closest red supergiant to Earth. From November 2019 to March 2020, this star experienced a historic dimming of its visible brightness. Usually having an apparent magnitude between 0.1 and 1, its visual brightness decreased to 1.6 magnitudes around 7-13 February 2020 — an event referred to as Betelgeuse’s Great Dimming. New research, published in the journal Nature, reveals that the star was partially concealed by a cloud of dust, a discovery that solves the mystery of the Great Dimming event.

Supergiant stars like Betelgeuse are naturally unstable, so their brightness fades periodically. But the scale of the Great Dimming Event was beyond anything seen before.

Betelgeuse’s dip in brightness led an international team of astronomers to point ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) towards the star in 2019.

Led by Dr. Miguel Montargès from the Observatoire de Paris and the KU Leuven’s Institute of Astronomy, the team used the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument on VLT to directly image the stellar surface, alongside data from the GRAVITY instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), to monitor the star throughout the dimming.

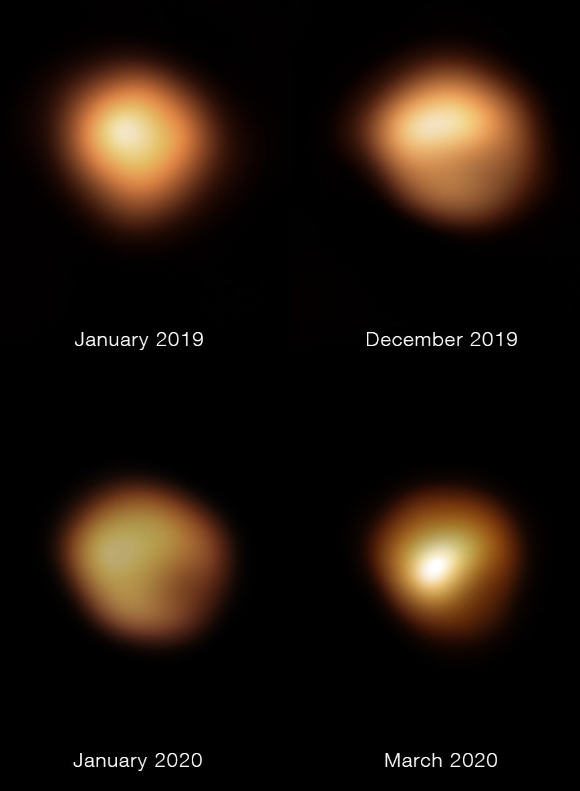

An image from December 2019, when compared to an earlier image taken in January of the same year, showed that the southern hemisphere of Betelgeuse was darker than usual in the visible spectrum.

The astronomers continued observing the star, capturing two other images in January and March 2020. By April 2020, the star had returned to its normal brightness.

“For once, we were seeing the appearance of a star changing in real time on a scale of weeks,” Dr. Montargès said.

“The images now published are the only ones we have that show Betelgeuse’s surface changing in brightness over time.”

The researchers found that Betelgeuse’s Great Dimming was caused by a dusty veil shading the star, which in turn was the result of a drop in temperature on its surface.

In other words, Betelgeuse let out a colossal belch.

Betelgeuse’s surface regularly changes as giant bubbles of gas move, shrink and swell within the star.

The scientists concluded that some time before the Great Dimming, the star ejected a large gas bubble that moved away from it.

What happened subsequently is of particular interest for our understanding of how stars and planets form and evolve.

When a patch of the surface cooled down shortly after, that temperature decrease was enough for the gas to condense into solid dust.

“We have directly witnessed the formation of stardust,” Dr. Montargès said.

“The dust expelled from cool evolved stars, such as the ejection we’ve just witnessed, could go on to become the building blocks of terrestrial planets and life,” added Dr. Emily Cannon, an astronomer at the KU Leuven’s Institute of Astronomy.

Sci News

So Orion will get to keep his bright red left shoulder for a while yet – and astronomers have added just a little more to our understanding of the universe.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD