Table of Contents

I am disappointed with the lack of sensible political leadership regarding the situation at Ihumatao, and even more disappointed with the media coverage of it which appears, in several quarters, to verge on advocacy for the squatters occupying the land.

There is much more to this story of Maori-Pakeha and Maori-Maori relations regarding contested ‘land – rights’ on this particular headland. It should be covered much more objectively. In that vast area between rhetoric and reality, I place my take on the affair:

1847: At Ihumatao local Maori, aided and guided by the Wesleyan Church Missionary Society, begin preparations to cultivate the area, cutting two large channels in order to drain the swamp-land in preparation for planting the following season.

1848-1850: Ngati-Whatua sell blocks of Ihumatao to Messrs Geddes and Imlay.

1851: Following the colonial government’s interjection into pre-emptive land sales (those taken outside government agency) the Geddes/Imlay purchase is scaled back and surveyors arrive to plot the land for benefit of the government (this was one way of financing the Treasury, effectively taxing the purchasers by way of land-grabs, to the government’s benefit). Local Maori strongly resist, pulling out survey pegs, and protesting the mistreatment of rightful pakeha purchasers. Ngati-Whatua chief Paore Tuhaere had previously expressed his feelings on this subject, very clearly:

“Friends, White People of Auckland, – Listen all of you. The Governor is unjustly taking the lands of the white people. Now I say this law of the Governor is wrong. Because I have sold the land to the white man. The money has been received by us, our eyes have seen the payment, and we were glad. But the Governor’s payment we have not seen, his claims are shallow, therefore I said this principle is wrong, is it not so, friends?”

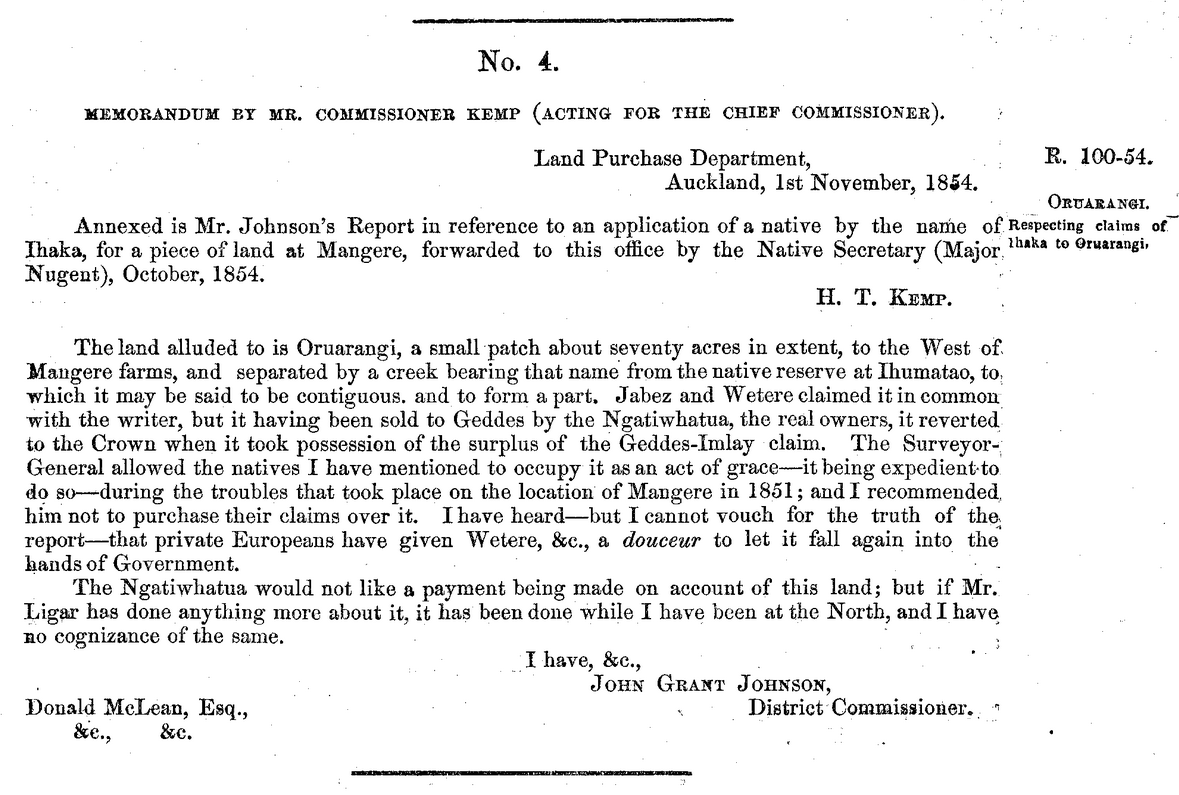

1854: John Johnson, District Land Commissioner, advises Donald MacLean, Chief Commissioner, of a possible dispute. He advises that local men; Ihaka of Ngati Te Ahiwaru and two others, descended from Tainui, have made a claim to the Oruarangi section of Ihumatao. Johnson advises against settling with them as Ngati-Whatua were the rightful proprietors and Ihaka’s people occupy Ihumatao only by the ‘grace’ of the Commissioner and in view of the 1851 ‘troubles’. Johnson reports some settlers possibly offered douceurs (bribes) to the native men to induce them to drop their claim.

1855-1858: The land is in limbo, un-surveyed and with competing claims.

1858: March 26th. A very large meeting of Maori is held on the land, attended by Auckland, Thames and Waikato tribes. By consent, and only after long talks, Te Ahiwaru are elevated to the place of rightful and permanent occupiers and the agreement placed in writing.

1858: June. The Maori King movement anoints Potatau Te Wherowhero, living then at Ihumatao, as their sovereign.

1862: Ihaka allegedly agitates for fellow Manukau tribes to join the King movement. Witnesses would later give evidence of Ihaka counselling Mohi, who definitely went to war, to ‘patu Pakeha’ to kill settlers. This claim would be denied and the evidence for it hotly contested.

1863: War is looming, the authorities are (willfully?) apprehensive of a combined Waikato tribes assault on Auckland; two proclamations are issued on July 9th, the first demands natives of Manukau declare allegiance to the Queen of England and Empire and lay down arms; or leave. The second requires ‘friendly natives’ stay indoors after curfew that they not be mistaken for ‘enemy’.

1863: July 11th the people of Ihumatao carry what they can and leave for the Waikato, with commenters surmising ‘Blood is thicker than water’. What they have to leave behind is shamelessly looted or arbitrarily destroyed, including their cultivations and all the improvements from nearly twenty years nurture and effort.

That darkness that resides in the recesses of the human soul, the propensity to profit from other human beings misery is bothered not a whit by race, or class, it is neither a solely Pakeha attribute nor a unique Maori characteristic. It is documented in history across millennia from the plains of Judea to the ghettoes of Warsaw, the ideological purges of the USSR down to the killing fields of Cambodia. It’s a permanent and disappointing character malady lurking deep in the collective soul of man and woman-kind forever ready to spring to the fore; this willingness to profit from adversity suffered by others.

1863: July 12th Ihaka, unwell, and the older of the Ihumatao people are arrested at Kirikiri and charged with ‘rebellion’. Their land is confiscated, Government agents take control of Ihumatao and offer grazing on the lands, at a price, to the cattle and horses of locals and refugee farmers from the troubled Waikato.

1863: November. Another imperative comes to light that helps explain the seemingly irrational decision for Manukau Maori to leave their flourishing community and venture south in the middle of Winter;

“I said, was it not very foolish for him to leave, and go to the Waikato (where he had said he intended to go). He said his reason was that the Governor and Ngapuhi were friends, and if the Maoris stayed at Ihumatao, and the soldiers did not kill them, the Ngapuhi’s would, as they were their old enemies.”

1863: Tainui allies are extremely annoyed, angered, by the treatment of Manukau kinsmen and the abject failure of the Governor to protect their property, some even cite it as the very reason they went to war – the loss of good faith, the failure to protect those who undoubtedly, at that point, had committed no wrong whatsoever toward anybody, indeed: ‘they were good neighbours and very much respected by the settlers around’.

1864: A scandal erupts as it appears all other cattle, including those of the refugee settlers, have been driven from Ihumatao in favour of the brother-in-law of the Crown agent; Vercoe’s own beasts. It becomes known as the ‘Ihumatao Job’.

1866: Following the cessation of hostilities ‘Native Compensation Courts’ are established to deal with unfair confiscations. Several applicants from Ihumatao are heard. It is recognised that Ihumatao consists of separate parts – Puketapapa (the site of the protest today) is recognised as property of Te Ahiwaru and therefore lost forever to them on account of ‘the whole tribe’ rebelling. The other two components of Ihumatao and the original owners are treated much more respectfully and several re-united with their land, about 260 acres of the total 1,100 acres taken.

1866: Gavin Wallace of county Argyll, Scotland moves onto the land at Puketapapa and his family will remain in situ 150 years.

1926: A Royal Commission of Inquiry investigates land grievances, finding the Ihumatao confiscations ‘excessive’.

1946: A full and final settlement of the remaining issues surrounding confiscation of Waikato-aligned properties is signed. The arrangement, allowing for a one-off payment of five-thousand pounds along with providing an annuity of one-thousand pounds per-year for the following forty-five years, is passed through both Houses of Parliament.

1985: After years of preparatory work The Waitangi Tribunal produces the “Manukau Report” raising concerns by local Maori including loss of land, water rights, and mana.

1998: Auckland Council approach Wallace’s descendants with a view to obtain the Otuataua Stonefields portion of their land for permanent preservation. The family sells the land to Auckland at a very low price, well below market value, believing that doing so is a ‘contribution to the public good’.

2006-2010: Auckland unsuccessfully attempt to buy the remaining land below market value.

2014: Fletchers buy the land, provisionally, dependent on planning consent. Local Maori object, but having exhausted legal avenues, negotiate with a view to better their outcome. They succeed.

2016: Fletchers announce the development. The occupation begins.

2019: You are here.

While it is easy to admire SOUL’s Ms Pania Newton’s intelligent, savvy, and sophisticated activism, and I have no doubt whatsoever her heart is totally committed to her cause, I cannot but find irony, and I wish that she could too, that the suggested solution to an unfortunate and distressing dissolution, trampling, of property rights in the nineteenth century is thought to be solved by dissolving and trampling on property rights in the twenty-first century; this surely cannot be. It must not be allowed to be. Two wrongs do not a right make.

For once, in the history this contested piece of real-estate, the rule of law must be considered uppermost; regardless of debatable and inventive claims or occupations by outsiders. This present arrangement between Te Kawerau-a-Maki and Fletchers must stand.

For the first time in nearly two-hundred years property rights; not might, nor fight, nor emotion, not opportunism, not activism, not anarchy, not belligerence, not envy nor revenge, and certainly not propaganda, must prevail at this special place which has been the centre of so many misunderstandings, and mischief.

Indeed, a cynic would point to the unfortunate parallels which shade SOUL’s moral stance. Although claiming altruism and preserving heritage are their motivations, one can reasonably ask if they are any different ipso facto to those that gathered at Puketapapa on that mid-Winter Sunday in 1863. On that day they awaited the removal of Ihaka’s people so that they could fall upon the property of others and convert it for their own benefit and gain. They destroyed in a day what had taken twenty years to create.

That is what SOUL is proposing; to fall upon a property they do not own in order to convert it to their own design. In doing so they will destroy what Kawerau-a-Maki have worked towards, that which they have cultivated, some say for up to forty years, in order to produce the present and real opportunity for their people.