Table of Contents

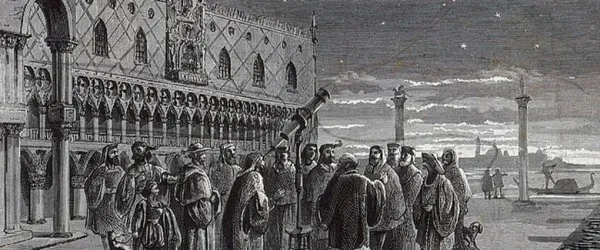

In 1633 Galileo was convicted of suspected heresy for providing support to the Copernican theory that the Earth moved around the Sun, a position which contradicted the teachings of the then ‘pulpit of truth’, the Catholic Church.

In the centuries that followed, the Catholic Church attempted to undo what it had done. But it wasn’t until 1992 that Pope John Paul II finally rectified one of the church’s most infamous wrongs. “We today know that Galileo was right in adopting the Copernican astronomical theory,” said the head of the Vatican’s investigation team.

In the 360 years between Galileo’s conviction and the recognition by the church that Galileo was right, the Earth nevertheless continued to move around the Sun. Because reality, as they say, is the ultimate arbiter of truth. For two-and-a-half years, we who questioned the government-approved narrative have been criticised, ostracised, vilified and censored. It’s not been easy for many. The pain has been real. The losses immense.

But all this time we waited. Patiently. Sometimes impatiently. We held to the truth of our convictions.

We did so because we knew the arbiter of truth does not stand behind ‘the pulpit of truth’, read the evening news or hold impressive scientific qualifications. We held to our convictions because we knew (or suspected we knew) the truth. We also knew the time would come when the truth would finally reveal itself to those who have, up to this time, believed the government-approved narrative. That time has arrived.

Might we now expect apologies to be delivered? Acknowledgement of the damage they have done to us and our country? A request for forgiveness? Like Galileo, however, we may need to be patient.

Last week the Atlantic magazine foreshadowed one approach which may be employed by the political, academic and media elites. “We need to forgive one another for what we did and said when we were in the dark about Covid,” wrote Emily Oster from Brown University as she argues for a pandemic amnesty. As you might imagine, the global reaction to this suggestion was swift and damning.

Will an amnesty right the wrongs inflicted upon us? Will it bring together our divided society? Will it undo the hurt and pain we endured, and still endure? Will it lead to justice for those who were maimed or died? It will, unfortunately, only lead to the opposite. The father who wrote the following in response to Emily Oster’s suggestion would find little comfort in an amnesty:

My daughter was a tattooist, worked in the hospitality industry, an entertainer and an artist. During the Covid lockdowns she had no purpose. She said “Dad, everything I do has been deemed non-essential, does that mean I’m non-essential?” The psychological hangover of the impositions placed on people were severe and the mental long-term effects acute. The empty space inside her grew. She left us three weeks ago. I miss her so much.

A further response to the mounting evidence against their narrative is that, like a cornered dog, the political, academic and media elites will attack those who stood up against them. It should come as no surprise then that it is at this time that they are labelling as ‘spreaders of disinformation’ and ‘potential terrorists’ those who are standing up against the narrative. ‘Keep an eye on those you know, and if necessary, dob them in’, is the message from the NZ Security Intelligence Service.

It is therefore becoming clear that, as the truth continues to reveal itself, we should not expect to be acknowledged, receive an apology or have our day of public vindication any time soon. That day will come, though. So what can we do until then?

Legend has it that Galileo muttered, “And yet it moves,” as he was forced to recant his view that the Earth moves around the Sun. Equally, until our day of public vindication, we can take quiet comfort that we have made decisions and hold views consistent with reality – the truth.

We should continue sharing our experiences with those who have walked the same path. In our Voices community we all receive the acknowledgement we can get nowhere else in society. We will be heard. And understood. In so doing we will also need to speak and listen with compassion and non-judgement for the decisions others have had to make.

We can – and we also must – continue speaking the truth. By doing so we can change the narrative and influence our wider community. Mattias Desmet writes: “Truth-telling is a way of speaking that breaks through an established, if implicit, social consensus. Whoever speaks the truth breaks open the solidified story in which the group seeks refuge, ease and security.” We will undoubtedly experience many emotions and challenges ahead. But if we choose to hold values which build connections with our wider community – love, compassion and respect for the truth – then our day of public vindication will come sooner.

And, unlike an amnesty, this will bring a sense of justice and closure that we all need and deserve.