Table of Contents

Humans have been obsessed with the idea of finding life on Mars since at least the 19th century. Interest in the 19th century was especially spurred by Giovanni Schiaparelli’s purported discovery of canali on Mars. That word, meaning channels, was misinterpreted into English as canals, with all the implications of artificial construction that word conveys.

The only problem was that the linear markings Schiaparelli and his followers, most famously the American astronomer Percival Lowell, claimed to see didn’t exist at all. They were, it was eventually realised, the result of badly resolved images from telescopes combined with a human propensity to find patterns where they don’t necessarily exist.

We’re still finding them.

Over the past decade, much excitement was generated by the apparent discovery of large seasonal blooms of methane on Mars. Methane being mainly produced by biological activity on Earth, the enthusiastic conclusion by many was that the same must apply on Mars. Except that methane can also be produced by non-biological causes, including the Mars Curiosity rover itself.

The fact that the spectrometers on the ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) has ever detected a trace of methane is a bit of a giveaway that there’s something else going on besides putative Martian microbes. Some scientists are now convinced that the detected methane is being generated inside the rover’s instruments themselves.

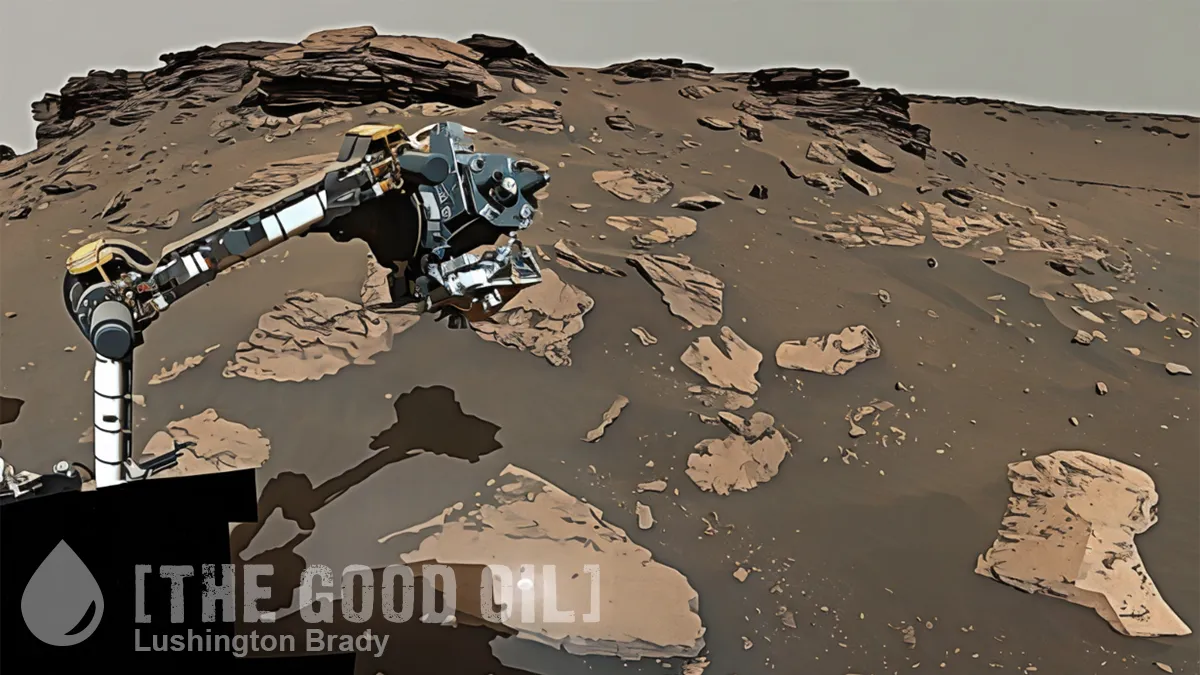

But hope in life on Mars springs eternal. A recent discovery by the Perseverance rover is being hailed as yet another telltale trace of life on the red planet.

In mid-2024, the Perseverance rover encountered a block of ancient mudstone, nicknamed Cheyava Falls, distinguished by its brick-red hue. This rock was laid down by water roughly four billion years ago. While most Martian rocks appear red due to a coating of oxidised (ferric) iron dust, Cheyava Falls is red through and through – the ferric iron is in the rock itself.

More intriguingly, Cheyava Falls is peppered with dozens of tiny pale spots, typically less than a millimetre across. These spots are fringed with a dark phosphorus-rich mineral, which also appears as tiny dots called poppy seeds that are scattered between the other spots. Associated with this mineral are traces of ancient organic compounds. (Organic compounds contain carbon and are fundamental to life on Earth, but they also exist in the absence of biology.)

So, why are people getting all worked up again? It’s because – so far – there’s no known non-biological process that produces these particular dots.

All living organisms on Earth harness energy through oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions – transferring electron particles from chemicals known as reductants to compounds named oxidants […]

When ferric iron is reduced to a different form, known as ferrous iron, it becomes soluble in water and either leaches away or reacts to form new, lighter-coloured minerals. The result is that many red rocks and sediments on Earth contain small bleached spots – “reduction spots” – strikingly similar to those found in Cheyava Falls. In fact, Perseverance subsequently spotted bleached features even more reminiscent of reduction spots at a site called Serpentine Rapids, but spent too little time there to analyse them and, unfortunately, didn’t collect any samples […]

The most plausible interpretation is that redox reactions occurred within the rock after it formed, transferring electrons from organic matter to ferric iron and sulphate, and producing bleached zones where ferric iron was depleted.

Notably, these reactions – especially sulphate reduction – don’t typically occur at the low temperatures this rock experienced over its history. Unless microbes are involved, that is. Microbial oxidation of organic matter can also produce phosphate minerals, like those found at Cheyava Falls.

But scientists can’t say for certain if the samples are by-products of life until they get them into a lab on Earth.

Perseverance has already collected a fragment of the relevant rock – we just have to go and get it.

Indeed, Nasa has been working with the European Space Agency on a mission to go to Mars, retrieve the samples of rock collected by Perseverance and deliver them to Earth. This would include the sample from the rock that’s the subject of the Nature study. However, the mission, known as Mars Sample Return, has run into trouble because of rising costs […]

Without getting samples back to laboratories on Earth, there’s only so much we can really know about what happened at Cheyava Falls four billion years ago. Even so, no entirely satisfying non-biological explanation accounts for the full suite of observations made by Perseverance.

That we know of, right now. This is the important caveat.

In astrobiology, the lack of a non-biological explanation isn’t where life detection ends – it’s where it begins. History tells us that when we can’t think of a non-biological explanation for something, it’s usually not because there isn’t one. It’s just that we haven’t thought of it yet.

So, the scientifically rigorous and honest thing to do is to set out to explore every possibility they haven’t thought of yet that excludes biology from the process. And work on getting the rocks back to Earth.