Table of Contents

History is said to be written by the victors – war history no less than others. So it’s often surprising to read loser’s accounts of famous military events. Through German Eyes, Christopher Duffy’s history of the Somme from the German side, reveals, among other things, just how close the British actually came to winning that titanic, bloody battle: had the British only known, German resistance was on the verge of cracking.

D-Day Through German Eyes by Holger Eckhertz is another eye-opener. From the perspective of the ordinary German soldier that they were building a “United States of Europe” to just what it was like to look out that morning and see the largest seaborne invasion in history bearing down on you.

Neal Stephenson’s 1999 novel Cryptonomicon and the 2014 film The Imitation Game both dealt with the massive, top-secret Allied code-breaking apparatus based in Bletchley Park. Less is known about their opponents in this shadow-boxing art of war, the German military radio network, code-named BROWN, based in the German town of Cuxhaven.

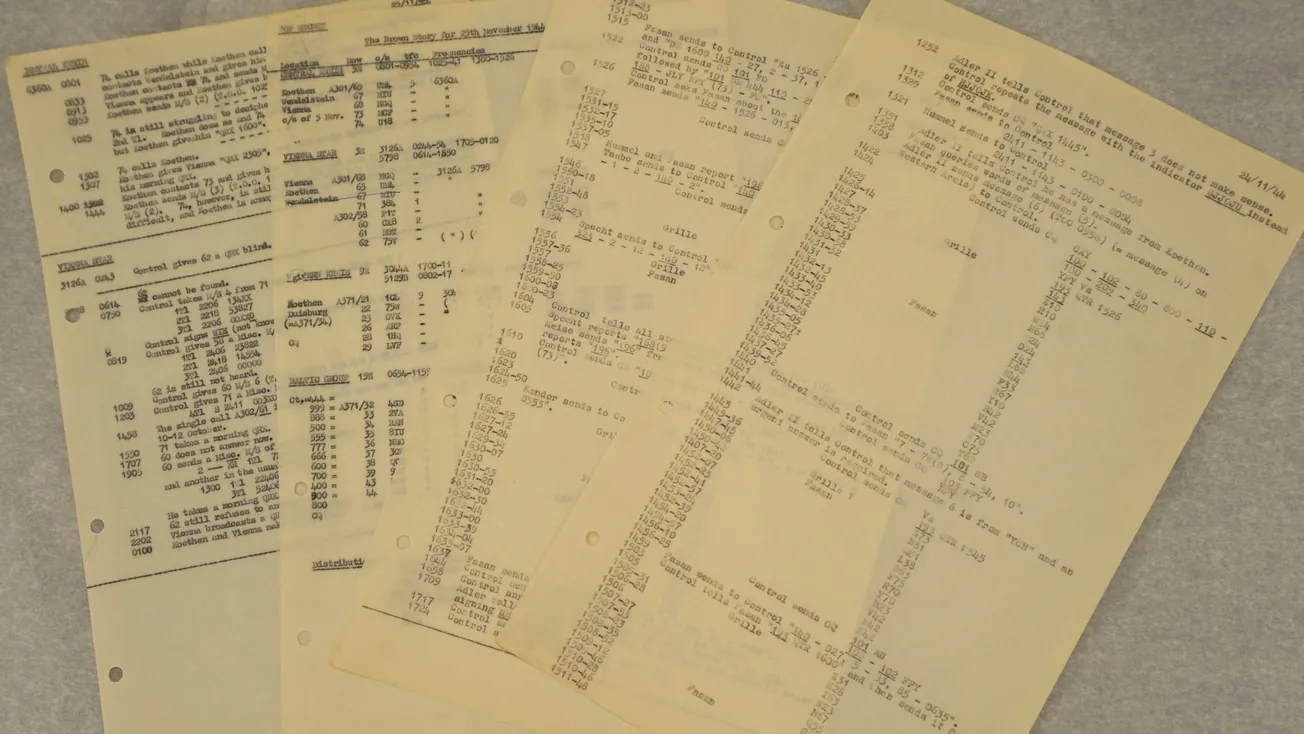

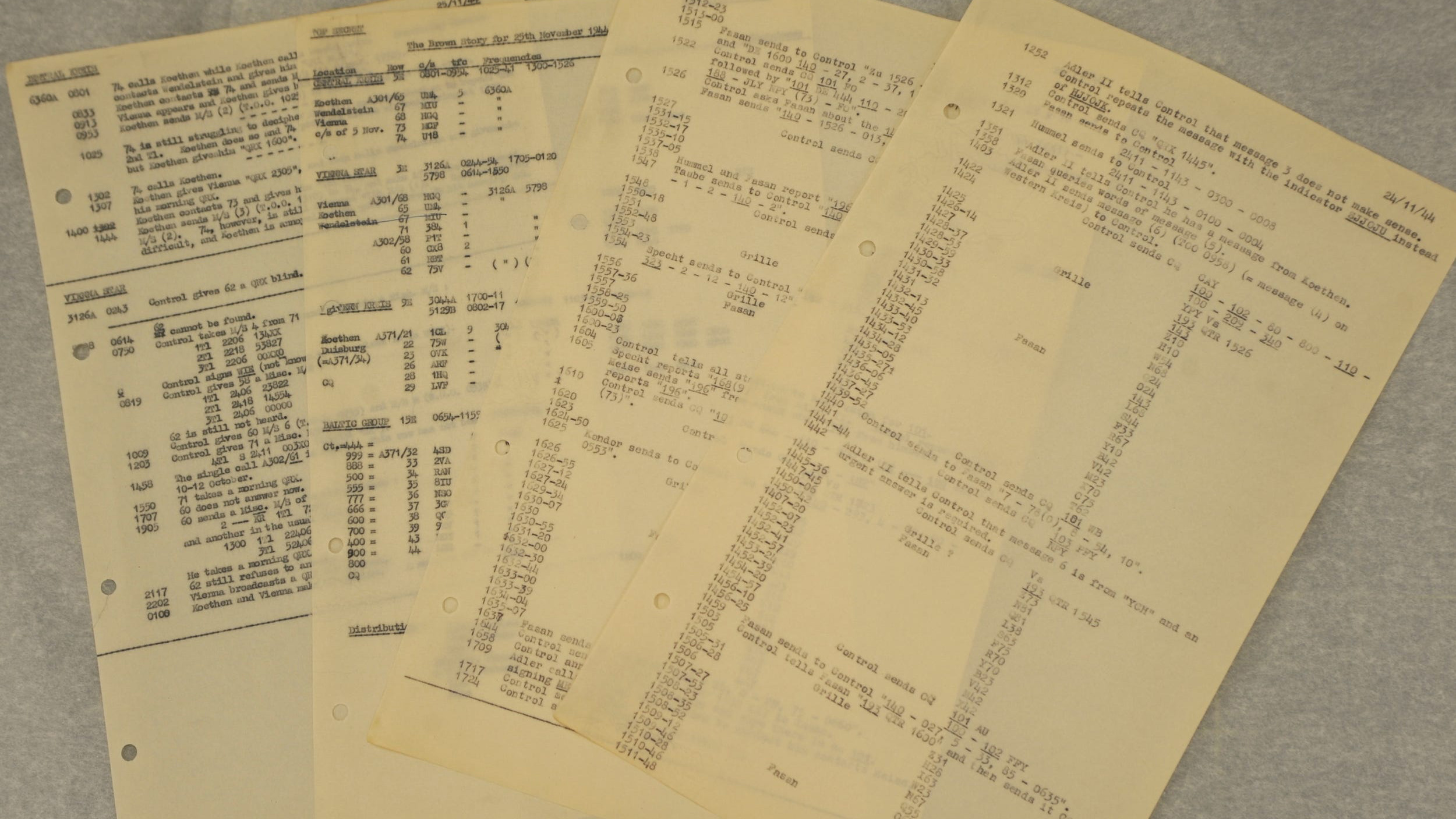

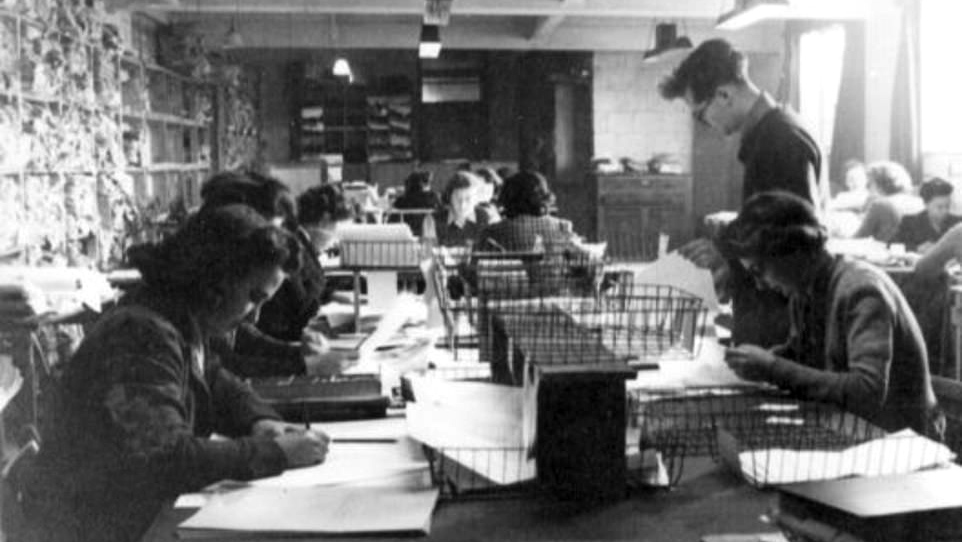

A new trove of documents released by the British government to mark the 75th anniversary of VE Day gives a rare glimpse of the people behind the secret apparatus of the German military machine. The newly-released messages, the last intercepted and decoded at Bletchley Park, show the last of Germany’s messengers preparing to close up shop for good on the final day of the War in Europe.

VE Day – Victory in Europe, the day the Allies formally accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany – was 8 May 1945. On the previous afternoon, as Allied forces captured Cuxhaven, the last of the German messengers still at his post, Lieutenant Kunkel, sent the last recorded message from the network.

“British troops entered Cuxhaven at 1400 on 6 May — from now on all radio traffic will cease — wishing you all the best. Lt Kunkel.”

That message was immediately followed by: “Closing down forever — all the best — goodbye.”

A message intercepted a few days earlier revealed German messengers on the Danish coast asking Control whether they had any spare cigarettes. The reply came: “No cigarettes here.”

But Cuxhaven’s military importance extended far beyond the vital German communications network. It was also part of another top-secret Nazi war effort – it was used as a site for V-2 rocket testing.

As the only site in Germany with an unrestricted over-water firing sector over the North Sea, Cuxhaven was once touted as “the Cape Canaveral of Germany”. Cuxhaven had been used for testing naval artillery since before WWI. Experiments in rocketry had begun there as early as 1933. A local rocket enthusiast, Hugo Woerdemann, studied rocketry at the Technical Hochschule in Dresden. He eventually wound up in Peenemuende, specialising in V-2 radio guidance, instrumentation, and telemetry.

Following the heavy bombing of Peenemuende by the Allies on 17 August 1943, the Nazis decided to disperse their research facilities. In early 1944, a detachment of researchers set up launch ramps for V-1 cruise missiles and continued development of the missile from Cuxhaven. In 1945, as the allied armies approached, V-2 rockets and their equipment were abandoned.

The British military quickly moved to document the V-2 technology before the knowledge was lost. German rocket troops were forced to demonstrate what they knew. Field Marshal Montgomery took a special interest in “Project Backfire” as it was dubbed. By late summer 1945 some two hundred Peenemuende scientists, 200 V-2 firing troops, and 600 ordinary POWs were transported to Cuxhaven.

After Backfire was finished, the Allies demilitarised the region and local enthusiasts began pursuing rocketry for peaceful purposes. Some touted the site as a future spaceport.

Meanwhile, even as the otherwise unknown Lt Kunkel quietly shut down the Nazis’ communications network, staff at the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) at Bletchley park celebrated. A teenaged Helen Andrews, now 94, said she remembered a festive atmosphere on VE Day.

“A bloke came into the room where we were working and said: ‘It’s all over. They’ve surrendered’.”

There was a tea party followed by music and dancing, she said. She described her emotions as a release from anxiety coupled with exhaustion.

Along with some friends she worked with, Mrs Andrews hitched a lift to London and headed down to Trafalgar Square, where people were singing and jumping in the fountains.

But the end of the War in Europe didn’t signal the end of work at Bletchley Park. GCHQ staff carried on, deciphering Japanese codes as well as monitoring German communications to confirm that Nazi forces were surrendering and that there would be no attempt to mount a last stand.

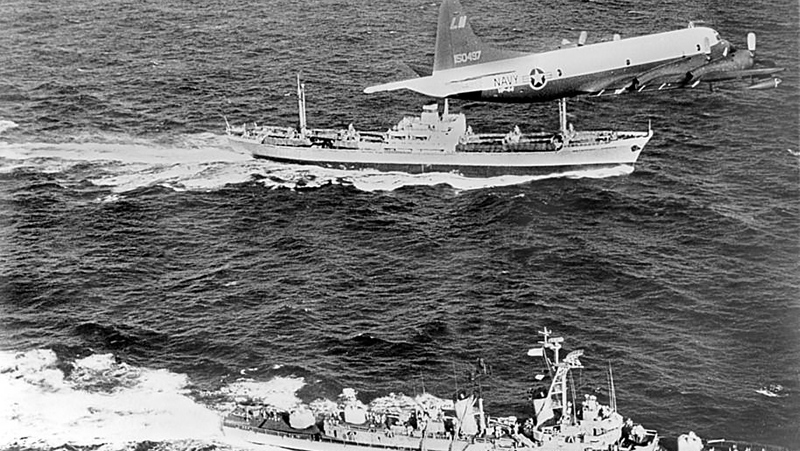

GCHQ played a key role during the Cold War, as well. In 1962 the US learned that the Soviet Union was secretly shipping nuclear missiles to Cuba, just 90 miles from America.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, GCHQ was intercepting position reports from Russian ships to determine whether the Soviets were planning to run the US blockade imposed by President John F Kennedy.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.