Table of Contents

Australia is in election mode again, even without an election being called. This is the Phony War phase of the upcoming elections and it’s in full swing. So I’ll conclude my three-part wrap-up of Australian Politics for the Confused New Zealander with a summary of the actual mechanics of elections and voting on this side of the ditch, and a brief survey of where the players currently stand.

Part One: The Boring Bit/Election Procedures

Like New Zealand, elections in Australia are not required to be scheduled on a set date. Instead, the prime minister has discretion to ask the Governor-General to call an election within a range of dates. Barring extraordinary circumstances, a term is three years. Specifically, an election must be held within three years of the first sitting of parliament following the previous election. Earlier elections are possible but, barring extraordinary circumstances such as a double dissolution (more on that shortly), the Governor-General is highly unlikely to grant an election in the first year of a new government.

In practice, only one government (the Alfred Deakin minority government of 1906–1910) has ever expired its full term. Since then, only Billy McMahon in 1972 and John Howard in 2007 have come close. On average, Australian governments have served terms of approximately 2.5 years.

Unlike New Zealand, Australia has a bicameral parliament, modelled on the UK Parliament, with its House of Commons and House of Lords. The lower house is the House of Representatives, the upper is the Senate. In keeping with our British origins, the Reps is furnished in green (representing the town commons where commoners would meet) and red (representing the ties by blood of the Lords).

While members of the House of Representatives only serve one term, senators serve two. So in a normal election, the entire House of Reps is dissolved, but only half of the Senate. A double-dissolution is an emergency election where both Houses are simultaneously dissolved, with all senators up for re-election. A double dissolution can only be called if the Senate twice rejects a piece of legislation which has passed a vote in the House of Representatives. Even if this condition is met, only a brave or reckless PM actually acts on it and calls a double dissolution election. There have only been seven in the 124 years of Federation, with, in most cases, the government either losing office or returned but unable to break the Senate deadlock. In only one case has a government been returned and subsequently been able to pass the contentious legislation.

The classic case is the 1974 double dissolution election, in which then-PM Gough Whitlam sought to break the Malcolm Fraser opposition’s hostile control of the Senate. The gambit backfired and Whitlam ended up with a reduction of his already-slim majority in the House of Representatives. In 1975, trying again to break the deadlock, Whitlam asked Governor-General Sir John Kerr (a Whitlam appointed and old ‘Labor mate’) to call a half-senate election. Instead, to Whitlam’s astonishment, Kerr exercised his constitutional reserve powers and dismissed Whitlam’s Government entirely.

So, an election is called: how do Australians vote?

There are a number of semi-myths and half-misunderstandings about Australian voting. Firstly, that it’s compulsory to vote, second that we don’t have voter ID laws.

Firstly, it’s compulsory for every eligible citizen over 18 years of age to register to vote and for enrolled voters to fill out and deposit ballot papers. Failing to do so attracts a nominal fine. However, it is not compulsory to actually vote for anybody. As long as they collect and lodge the ballot papers, an Australian voter has fulfilled their legal requirements. They can vote according to procedure, or not: even draw a dick on the paper and lodge it. A paper that is not filled correctly is called an ‘informal’ or ‘donkey’ vote. In practice, 92 per cent of Australians fill their ballots correctly.

With regard to voter ID, Australia does have requirements, but they are reasonably hands-off. To enrol to vote in the first place, an Australian must provide satisfactory identification, such as a driver’s licence, passport or similar. Then your name is registered on the electoral rolls. Rolls are based on the voting district in which you live, so if you move out of your current district, you must update your details with the Australian Electoral Commission.

On election day you go to a polling booth in the relevant electorate, where a poll worker asks your name and address, crosses it off the paper list in front of them and hands you your ballot papers. So, there is nothing to stop a voter going to multiple polling places and collecting and lodging multiple ballots – except that rolls from all polling booths are cross-checked after voting closes. So multiple voting will be caught. Again, in practice, just 0.1 per cent of voters filled in multiple ballots at the 2016 election, most apparently innocently. There have been a handful of cases of people voting up to 11 times.

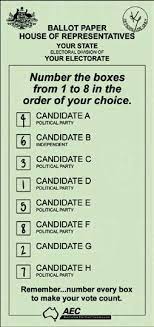

When it comes to filling out ballot papers, voting laws have been streamlined over time to make it as simple as possible. Voting is preferential, rather than first-past-the-post (as in the UK). That is, instead of marking a single candidate, voters must number candidates in order of preference. The two houses have slightly different procedures.

Voting in Australia is strictly pencil and paper. It may seem archaic, but it leaves an indisputable paper trail that can’t be falsified with a bit of code.

For the lower houses, voters collect a green ballot with typically half-a-dozen candidates or less, and mark all in order of preference. When votes are tallied, first preference votes are counted until one candidate has more than half of all votes. If no one does, the candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated. The ballot papers for the eliminated candidate are then counted for second preferences and votes distributed to remaining candidates accordingly. This process goes on until one candidate tallies more than half of the vote.

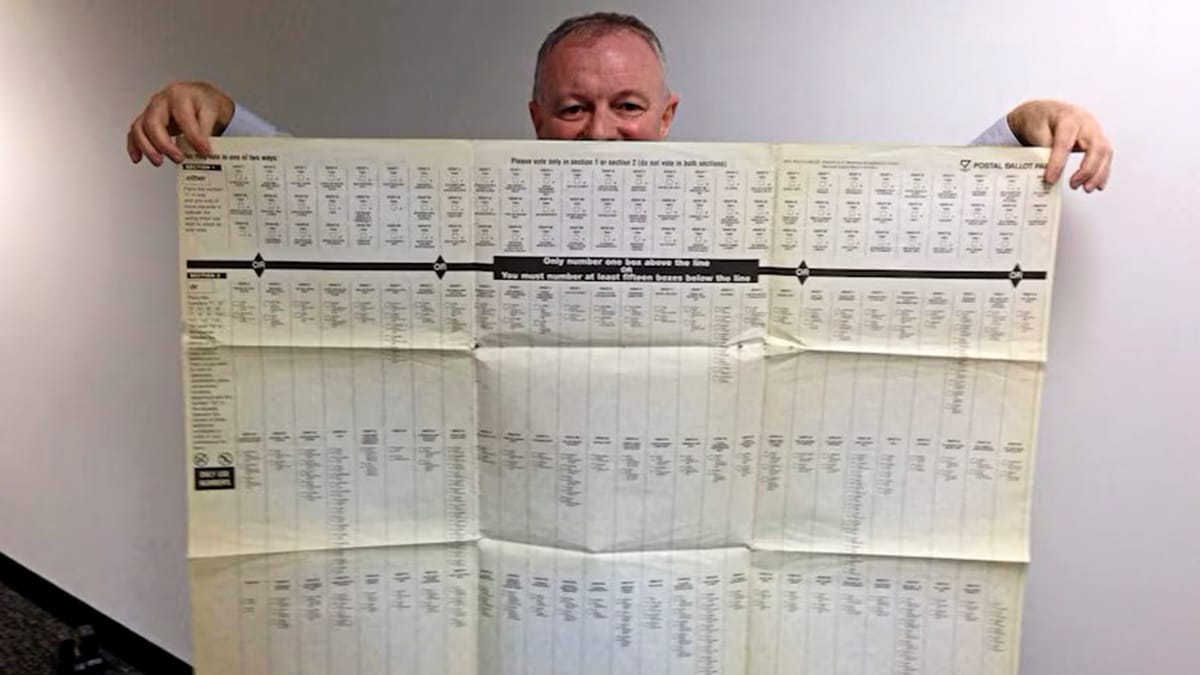

Voting for the Senate is another beast entirely. Senate voting is for a whole state rather than a district. Also the playground of minor parties, micro-parties and independents, Senate candidates can number well over 100. In some elections, some state Senate papers have been over a metre wide. Except complete political wonks (like yours truly), no one wants to bother filling out all 100, in order of preference.

So, voters have a number of options. ‘Above the line’ voting means you only have to number at least six boxes, from one to six. Above the line voting is by party rather than candidate. The voter is leaving it up to the parties to decide how their preferences are distributed.

If you vote ‘below the line’, where every single candidate is listed, you have the option of filling in at least 12, in order of preference. Or you can really bite the bullet and fill in all 100 or so. Wonk that I am, I usually do – if only for the pleasure of putting every single Greens candidate at the bottom of the pile.

While preferential voting can sound complicated, and can result in a party with a smaller first-preference vote winning (for instance, Labor in 2022 only accumulated 32 per cent of first-preference votes), it works on the principle that the most voters are the most satisfied. For instance, while a voter might want Candidate Green to win, they’d presumably prefer Candidate Red over Candidate Blue.

Compare that with first-past-the-post voting in the UK: although Reform tallied nearly as many votes as the Lib-Dems, they only garnered a fraction of the seats. Under a preferential system, many Conservative votes would likely have flowed to Reform, boosting their representation to something closer to the overall public mood.

Part Two: The Political Landscape Ahead of Election 2025

So, when an election will be held is a secret known only to PM Anthony Albanese, but it must be held by the end of May. Australian election campaigns are typically short. The 2016 election was a six-week slog that left Australians election-fatigued and pissed off. Most campaigns are around three weeks to a month. So, Australians can expect an election announcement any time in the next six weeks.

One option might be calling the election just before Easter, meaning that Australians will be in holiday mode and unlikely to pay as much attention to election news. At the same time, though, having a campaign during a holiday period would seriously piss voters off and look utterly desperate.

But the Albanese Government is so deep in the poll poo that they’re perfectly willing to piss off a lot of people with obviously desperate stunts. Such as holding extraordinary mass citizenship rallies in Muslim-dominated Western Sydney. Which just happens to be Labor heartland, which Anthony Albanese critically must hold onto if he’s to have even a hope of staying in power.

Polling indicates that Albanese is in deep, deep trouble. Elected on a record-low of 32 per cent of first-preference votes, Albanese squandered what little political capital he had with the ‘Indigenous Voice’ referendum. This was a policy which had never been discussed once during the 2022 election, yet it was literally Albanese’s very first policy announcement. Australians were already simmering in deep disquiet over rising cost of living. Especially electricity prices, which Albanese promised 100 times to lower during the election campaign, before presiding over non-stop rises of up to 25 per cent. Nor were Australians inclined to vote for such an obviously racially-divisive proposal which appealed only to elites and activists.

The referendum was resoundingly defeated and Albanese’s authority and political standing fatally wounded. Unlike UK PM David Cameron, who resigned when he lost the Brexit referendum, Albanese hung on for death by a thousand poll cuts. The ineluctable poll trajectory since has been down and down. None of the vote-buying (and taxpayer-funded) policy announcements (tax cuts, bill relief, childcare subsidies) have diverted the poll trends an inch.

On the other hand, the Voice campaign was the making of the coalition opposition, and leader Peter Dutton. Having bitten the bullet and made the principled decision to oppose the referendum, Dutton touched on a deep vein of disquiet with the political status quo. Since then, Dutton has repeatedly set the political agenda. While still not crazy-brave enough to call the ‘Net Zero’ scam for the disaster that it is, Dutton has instead proposed the equally audacious policy of Australia finally embracing nuclear power.

While Labor ran for cover from Muslims and the far-left on Israel, Dutton has unequivocally condemned their appalling anti-Semitism, starting with the dreadful night of October 9, 2023, when a Muslim mob stormed the Sydney Opera House chanting ‘Gas the Jews’. Dutton is also echoing, however cautiously, the anti-woke agenda sweeping Western democracies.

Answering back to the witless nonsense about a supposed coalition ‘woman problem’, Dutton has assembled a team which includes popular, genuinely conservative, women such as Jacinta Nampijinpa Price (often touted as a future PM), Sussan Ley, the Nationals’ Bridget McKenzie and Tasmanian senator Jane Hume.

But Dutton is in danger of letting Labor set the running on the election campaigning with the one issue they have left in their tattered policy bag: Medicare. Health and education have traditionally been Labor’s strong points. Well, education is obviously a loser, now: Australians have watched educational standards steadily eroded while Labor-aligned teachers’ unions steadily resist the back-to-basics policies that are delivering dividends in Catholic schools. Worse, woke nonsense, from ‘Indigenous science’ to ‘rainbow’ gender grooming, have supplanted reading and maths as curriculum priorities.

So, health is all that Labor have left. Meaning, Medicare. Like their UK counterparts with the NHS, Labor have fetishised Medicare, no matter the cost. Worse, during each of the last three elections, they have repeated the same ‘Mediscare’ tactic of claiming, against all evidence, that the coalition is planning to ‘destroy Medicare’, should they win. It’s such an obvious lie that even the ABC has called it out, but it’s all Labor has.

That, and other peoples’ money. Labor’s big, pre-election policy splash is throwing nearly nine billion dollars of taxpayer’s money at improving bulk-billing. This is where a GP only charges at the scheduled Medicare fee, eliminating out-of-pocket payments. Never mind that bulk-billing rates were higher under the last coalition government than Labor.

The other likely big losers at the election are the Greens. The Greens’ vote has never topped 13 per cent, and usually chugs along at around 10 per cent, nationally. But their vote is highly concentrated, unsurprisingly, in the wealthy innermost suburbs of the big cities: Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. They have also benefitted from preference flows from Labor.

But in recent elections, a state vote in Queensland and a round of federal by-elections in Melbourne, the Greens were decimated. The Melbourne result was particularly telling: in the inner suburb of Prahran, Melbourne’s traditional gay suburb, without Labor preferences to boost them, the Greens lost to a coalition candidate. On the same weekend, Labor came within a knife-edge of losing one of their stronghold seats.

After 18 months of rising anti-Semitism, with the Greens often at the forefront, Albanese is under intense pressure to put the Greens last on every Labor voting ticket. If he does, the Greens will be crushed.

Where the Greens’ vote is highly concentrated in a handful of seats, the minor conservative parties are dispersed across the nation, making it much harder for them to gain representation, especially in the lower house. Leading the conservative minors is Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party. While One Nation’s vote has fluctuated wildly over time, in recent months, they’ve begun a steady rise, closing on the Greens, with a nine per cent primary vote in latest polls.

Calling the Election?

It’s too early and too foggy to call the election concisely, yet. But, so far, it’s Dutton’s to lose. The only real question is how badly Albanese will be clobbered. At the moment, a minority government is Labor’s best hope – and even that’s an outside chance. Mostly likely is a Dutton minority government, though they might surprise everyone with a Donald Trump-style sweep of the board.

Almost certainly, preference flows from minor parties will be critical. While Dutton has done much to claw back the coalition’s primary vote, it remains dangerously low at 39 per cent (compared to Labor’s 25 per cent). On a two-party preferred basis, the coalition leads, but whether by enough to form government in their own right is the big question.

Voters are clearly still disillusioned with the major parties – especially conservative voters who grew increasingly frustrated as the party was taken over by the so-called ‘moderates’. Woke, wet ‘LINOs’ (Liberal In Name Only) like Malcolm Turnbull, who were just Greens wannabes in more expensive suits, or stand-for-nothing jellybacks like Scott Morrison. Whether Dutton can convince enough traditional Liberal voters to come back to the fold will be critical.