Table of Contents

Rebekah Barnett

Rebekah Barnett reports from Western Australia. She is a volunteer interviewer for Jab Injuries Australia and holds a BA in Communications from the University of Western Australia. Find her work on her Substack page, Dystopian Down Under.

The Australian Government’s proposed new laws to crack down on misinformation and disinformation have drawn intense criticism for their potential to restrict free expression and political dissent, paving the way for a digital censorship regime reminiscent of Soviet Lysenkoism.

Under the draft legislation, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) will gain considerable expanded regulatory powers to “combat misinformation and disinformation,” which ACMA says poses a “threat to the safety and wellbeing of Australians, as well as to our democracy, society and economy.”

Digital platforms will be required to share information with ACMA on demand, and to implement stronger systems and processes for handling of misinformation and disinformation.

ACMA will be empowered to devise and enforce digital codes with a “graduated set of tools” including infringement notices, remedial directions, injunctions and civil penalties, with fines of up to $550,000 (individuals) and $2.75 million (corporations). Criminal penalties, including imprisonment, may apply in extreme cases.

Controversially, the government will be exempt from the proposed laws, as will professional news outlets, meaning that ACMA will not compel platforms to police misinformation and disinformation disseminated by official government or news sources.

As the government and professional news outlets have been, and continue to be, a primary source of online misinformation and disinformation, it is unclear that the proposed laws will meaningfully reduce online misinformation and disinformation. Rather, the legislation will enable the proliferation of official narratives, whether true, false or misleading, while quashing the opportunity for dissenting narratives to compete.

Faced with the threat of penalty, digital platforms will play it safe. This means that for the purposes of content moderation, platforms will treat the official position as the ‘true’ position, and contradictory information as ‘misinformation.’

Some platforms already do this. For example, YouTube recently removed a video of MP John Ruddick’s maiden speech to the New South Wales Parliament on the grounds that it contained ‘medical misinformation,’ which YouTube defines as any information that, “contradicts local health authorities’ or the World Health Organization’s (WHO) medical information about COVID-19.”

YouTube has since expanded this policy to encompass a wider range of “specific health conditions and substances,” though no complete list is given as to what these specific conditions and substances are. Under ACMA’s proposed laws, digital platforms will be compelled to take a similar line.

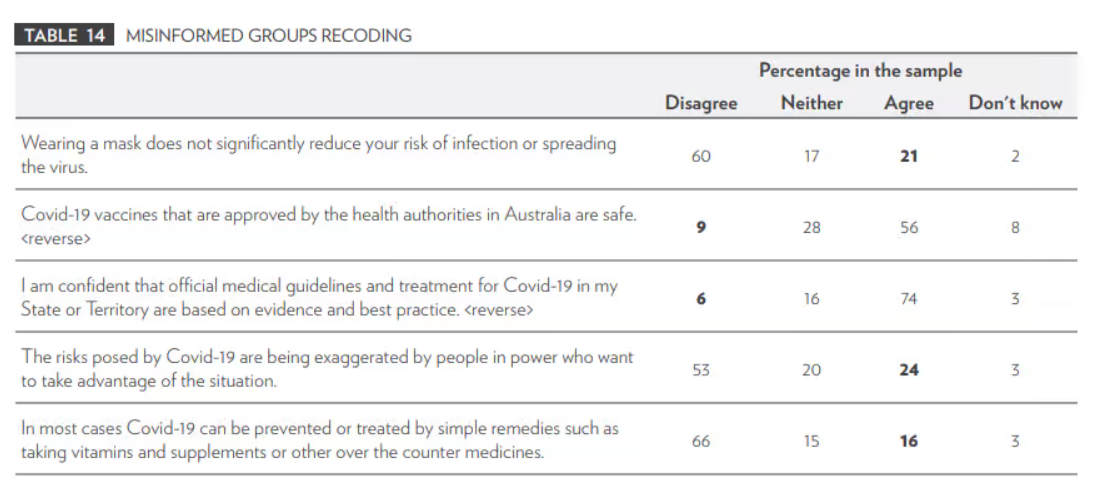

This flawed logic underpins much of the current academic misinformation research, including the University of Canberra study which informed the development of ACMA’s draft legislation. Researchers asked respondents to agree or disagree with a range of statements ranging from the utility of masks in preventing Covid infection and transmission, to whether Covid vaccines are safe. Where respondents disagreed with the official advice, they were categorised as ‘believing misinformation,’ regardless of the contestability of the statements.

The potential for such circular definitions of misinformation and disinformation to escalate the censorship of true information and valid expression on digital platforms is obvious.

Free expression has traditionally been considered essential to the functioning of liberal democratic societies, in which claims to truth are argued out in the public square. Under ACMA’s bill, the adjudication of what is (and is not) misinformation and disinformation will fall to ‘fact-checkers,’ AI, and other moderation tools employed by digital platforms, all working to the better-safe-than-sorry-default of bolstering the official position against contradictory ‘misinformation.’

But the assumption that such tools are capable of correctly adjudicating claims to truth is misguided. ‘Fact-checkers’ routinely make false claims and fall back on logical fallacies in lieu of parsing evidence. In US court proceedings, ‘fact-checker’ claims are protected under the First Amendment, confirming that the edicts of ‘fact-checkers’ are just opinion.

Recent reporting on the gaming of social media moderation tools, most notably from the Twitter Files and the Facebook Files, shows that they comprise a powerful apparatus for promoting false narratives and suppressing true information, with significant real-world impacts. Take the Russia collusion hoax, which was seeded by think tanks and propagated by social media platforms and news media. The suppression of the Hunter Biden laptop scandal is thought to have swung the 2020 US election outcome.

ACMA seeks to curtail expression under the proposition that misinformation and disinformation can cause ‘harm,’ but the scope is extraordinarily broad. A shopping list of potential harms includes: identity-based hatred; disruption of public order or society; harm to democratic processes; harm to government institutions; harm to the health of Australians; harm to the environment; economic or financial harm to Australians or to the economy.

The overly broad and vague definitions offered in the bill for ‘misinformation,’ ‘disinformation,’ and ‘serious harm’ makes enforcement of the proposed laws inherently subjective and likely to result in a litany of court cases – to the benefit of lawyers and the institutionally powerful, but to the detriment of everyone else.

Moreover, the definition of ‘disrupting public order’ as a serious and chronic harm could be used to prevent legitimate protest, a necessary steam valve in a functioning democracy.

ACMA says that the proposed laws aren’t intended to infringe on the right to protest, yet the erosion of protest rights during Covid lockdowns proves that politicians and bureaucrats are prone to take great latitude where the law allows it. The right to protest was effectively suspended in some states, with Victorian police using unprecedented violence and issuing charges of incitement to deter protestors.

In the US, the involvement of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in censoring online speech and, in particular, its framing of public opinion as ‘cognitive infrastructure’ demonstrates how even policies designed to combat ‘threats to infrastructure’ can be subverted as a means clamp down on ‘wrong-think.’

In the past, extreme censorship has led to mass casualty events, such as the Soviet famine of the 1930s brought on by Lysenkoism. Biologist Trofim Lysenko’s unscientific agrarian policies were treated as gospel by Stalin’s censorious Communist regime. It was reported that thousands of dissenting scientists were dismissed, imprisoned, or executed for their efforts to challenge Lysenko’s policies. Up to ten million lives were lost in the resultant famine – lives that could have been saved had the regime allowed the expression of viewpoints counter to the official position.

History tells us that censorship regimes never end well, though it may take a generation for the deadliest consequences to play out. The draft legislation is now under review following a period of public consultation. Hopefully, the Australian Government will take the historical lesson and steer Australia off this treacherous path.