Table of Contents

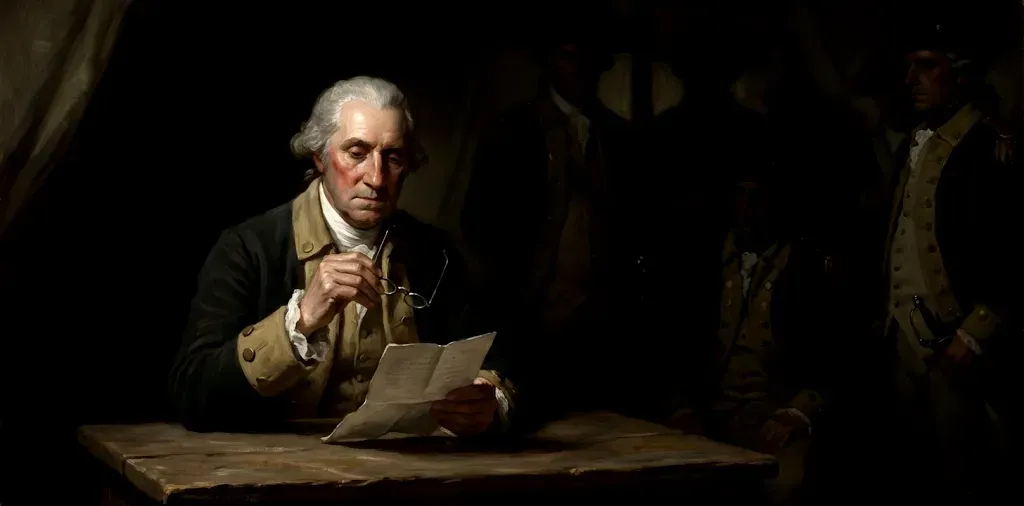

Francis Forde

P-hacking, HARKing, outcome switching, and Salami-slicing. Despite sounding like a list of manoeuvres to improve your sexual prowess, the research practices depicted by these terms paint a much less alluring picture. In his new book Science Fictions, Kings College lecturer Stuart Ritchie discusses the many shameful research practices that seem to be in wide circulation throughout the sciences.

Due to perverse incentives, reliance on trust, and a sad abundance of nefarious researchers, large swaths of the scientific literature are being undermined. While most researchers are good-natured, and many of their findings are of real value, Ritchie makes the case that fraud, bias, negligence, and hype are working to unravel the reputation that science has fought hard to establish.

As fake news gains a permanent slot among our daily media provisions, one would hope that the findings rolling out of research universities would allow us to properly situate ourselves within reality. We should be able to look to the leading journals in various fields and learn what is most probably true about the universe, about human behaviour, and about the bodies in which we reside. Yet, while rocket ships, FMRI, and vaccines all demonstrate the obvious functionality and rigours of the scientific method, recent investigations have shown that much of our knowledge is being built upon shaky ground. From power posing in humans to neoteny in Russian foxes, the scope of scientific misconduct expands far and wide throughout the many disciplines of the academic world.

But before introducing us to several examples of malpractice, Ritchie first highlights some scientific principles worth striving towards. These are known as the Mertonian Norms. Consisting of four pillars – universalism, disinterestedness, communality, and organised scepticism – the Mertonian Norms are proposed as requisites for proper, trustworthy science to be performed. Once employed, scientists should then be able to filter out erroneous findings with great haste. Data will be accessible to others, methods will be followed scrupulously and noted in detail, and conflicts of interests will be avoided or clearly stated upfront. An efficient system such as this, devoid of status hungry individuals, would propel human understanding to new heights.

Sadly, this rose-tinted caricature of science is quickly erased from the mind of the reader. In its place, we are left with the despairing image of an eager researcher hunting for unicorns atop arid land. Driven by the ‘publish-or-perish’ culture, Ritchie details the woeful accounts of researchers who ignored the necessary precautions of good scientific work. With the hopes of fame (or perhaps fortune) in mind, their fruitless efforts burdened taxpayers with a large bill in exchange for findings that do not map on to reality.

Fortunately, the effects of dubious science are often minor. Learning that a famed study failed to replicate (such as one which claimed that holding a hot beverage changes your assessment of another person’s personality) is unlikely to cause a massive stir in your worldview. But in some more consequential fields, like surgery, the effects of such negligence can be (and indeed have been) fatal. This is what is so eye-raising about Science Fictions. It opens the reader up to an astounding number of cases in which researchers in well-respected fields have propagated unverified claims, bogus data, and experimental designs that would barely pass muster in an introductory psychology class.

If a paper in feminist glaciology fails to follow proper scientific procedures, we may feel annoyed or scornful. But learning that a surgeon at a leading University in Sweden was able to perform multiple trachea transplants (a procedure which proved deadly) and was then defended despite an investigation proving his ineptness, leaves one utterly appalled. It is a different level of irresponsibility. We expect that any field so intimately involved with humans ought to have an extra layer of care and due diligence. But Ritchie wants to show us that our intuitions about medical research (and research more generally) need a reality check. While it may often meet our expectation of being organised, controlled, and performed in a calm manner, often is not enough.

Although somewhat idealistic, Ritchie hopes that all citizens should be able to trust the research going on in universities and medical institutions. But for this to happen, he believes that the domain of research itself needs to undergo change. To avoid a build-up of the unreliable studies which currently plague many scientific journals, they must first make themselves less hospitable to the kind of research practices that we encounter throughout this book.

While faith in science remains high, a continuation of current behaviours is likely to produce a growth of scepticism and distrust among the public. As outside forces create confusion by spreading alternative narratives and different ‘ways of knowing’ – which is of course not the fault of scientific institutions – scientists must be transparent about their past wrongdoings and clearly show the pathway forward. And let’s face it, most of us don’t know a darned thing about how the process of scientific thinking, experimentation, and publication occurs. We just look to those we trust (whether they’re experts in a field or grifters on YouTube) and try to form opinions.

So, scientists must make themselves worthy of our trust. And obviously, hiding their pockmarked past and engaging in the questionable practices Ritchie talks about is not a plausible way to achieve this. Instead, we need good scientists and honest science communicators. We also need citizens and people in power to have a basic understanding of scientific practices. In pursuit of this, a good first step would be for all of us to read Stuart Ritchie’s Science Fictions. This will put us in a better position for sorting the wheat from the chaff, as it provides guidance on how to read a scientific paper and how to spot dodgy scientific methods.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please share it.