Table of Contents

Douglas Adams once wrote that the past is like a foreign country: “They do things exactly the same there”. The truth of that quip is borne out more and more every time we get a glimpse of the thoughts and doings of ordinary people in the past.

Most historical records are, until relatively recently, the records of the elite: kings, generals, religious readers. This is not so much because literacy was much less common — in fact, basic literacy may have been more widespread than we usually give credit — but because writing material like paper was (in the West at least) scarce and expensive for a long time. Papyrus and vellum, even more so.

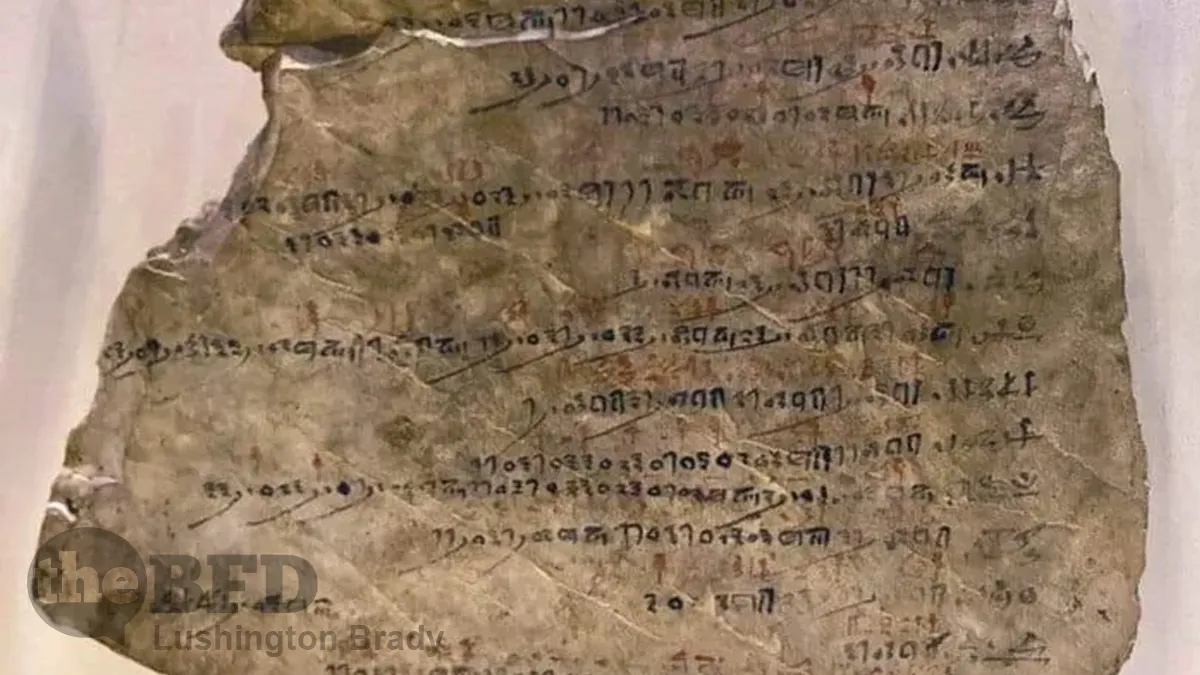

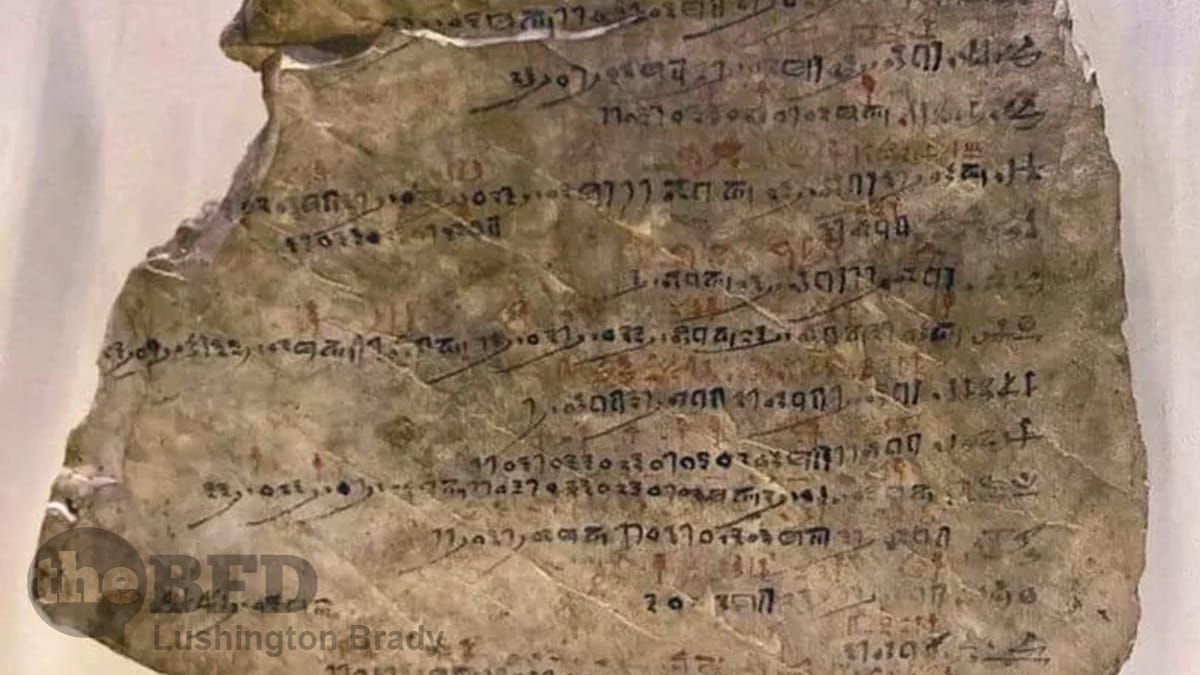

But, as we are discovering, the common folk often made do with cheaper alternatives. The millions of clay cuneiform from Mesopotamia are just one example. Another is the ostraca of ancient Egypt. Ostraca are simply shards of broken pottery.

Ancient Egyptians viewed ostraca as a cheaper alternative to papyrus. To inscribe the shards, users dipped a reed or hollow stick in ink. Though most of the ostraca unearthed in Athribis contain writing, the team also found pictorial ostraca depicting animals like scorpions and swallows, humans, geometric figures, and deities, according to a statement from the University of Tübingen, which conducted the excavation in partnership with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

There are tens of thousands of ostraca known to exist. A recent find, from 2000 years ago in the ancient city of Athribis, has added over 18,000 more.

A large number of the fragments appear to be linked to an ancient school. Over a hundred feature repetitive inscriptions on both the front and back, leading the team to speculate that students who misbehaved were forced to write out lines—a schoolroom punishment still used (and satirized in popular culture) today.

“There are lists of months, numbers, arithmetic problems, grammar exercises and a ‘bird alphabet’—each letter was assigned a bird whose name began with that letter,” says Egyptologist Christian Leitz in the statement.

Smithsonian Magazine

Like the ancient graffiti of Pompeii, the more we learn about people from the past, the more like us they seem. Only a fraction of Mesopotamian cuneiform have been translated, but they include everything from the earliest customer complaints to begging letters sent to relatives.

Ostraca offer a similar window into the everyday past. Besides school students doing lines, there are receipts and shopping lists. Not to mention attendance records that include the world’s earliest-recorded “sickies”. An ostraca from 3200 years ago records excuses for worker absenteeism, from “embalming brother”, to “brewing beer” and “bitten by scorpion”.

Another, written on a fragment of limestone, records a man named Sennefer listing his donkeys and their pedigrees by name:

Tamytiqeret daughter of Kyiry

Paounsou son of Tamytiqeret

Pasaiou son of Pasab

Paankh [son of?] Pakheny

Paiou son of Ramessou

Aside from the charming fact that Egyptians named their pets and livestock (donkeys weren’t supplanted by camels till more than a thousand years later), the meanings of the names are delightfully insightful.

Tamytiqeret, the only female donkey, means ‘the excellent cat’ – and this isn’t the only animal name among the donkeys. Five of the other names belong to other four-legged beasts: Paounsou, ‘the wolf’; Pasaiou, ‘the pig’; Pasab, ‘the jackal’; Paankh, ‘the goat’ (or perhaps instead ‘the living’); and Paiou, ‘the dog’. Why give animals the names of other animals? Do they reflect the donkeys’ individual characters, behaviour, or appearances? As for the other names, Kyiry translates as ‘another companion’, Pakheny as ‘the rower’, and as for Ramessou, what was it about this donkey that reminded Sennefer of his king, Rameses?

Papyrus Stories

Not only were Egyptian workers apparently chucking sickies to make homebrew and embalm their brothers, they also weren’t backward about bitching about their bosses — to their faces. Some 3000 years ago, a drafstman name Prehotep wrote a letter to his boss, a local scribe named Qenhirkhopeshef.

“What’s the meaning of this negative attitude that you are adopting toward me? I’m like a donkey to you. If there is work, bring the donkey! And if there is fodder, bring the ox! If there is beer, you never ask for me. Only if there is work (to be done), will you ask for me.

Upon my head, if I am a man who is bad in (his) behaviour with beer, don’t ask for me. It is good for you to take notice in the Estate of Amon-Re, King of the Gods, life, prosperity, health.

P.S. I am a man who is lacking beer in his house. I am seeking to fill my stomach by my writing to you.”

Papyrus Stories

A stingy boss and no beer makes Prehotep very grumpy. I’m sure we can all relate.