Table of Contents

In the movie Zoolander, male model Derek Zoolander (Ben Stiller) famously has a repertoire of a whole three looks. Turns out that Zoolander’s about one-hundredth as expressive as your pet cat.

Cats, according to a recent study, have nearly 300 different facial expressions. Surprisingly, not all of them are used to say, Feed me and go away, human.

In a study published in the journal Behavioural Processes last month, two US scientists counted 276 different facial expressions when domesticated cats interacted with one another.

“Our study demonstrates that cat communication is more complex than previously assumed,” study co-author Brittany Florkiewicz, an evolutionary psychologist at Lyon College in Arkansas, told CNN Wednesday, adding that their findings suggest that domestication has a significant impact on the development of facial signaling.

Although it’s generally accepted that cats are nowhere as domesticated as dogs, like their canine counterparts, cats have made a lot of evolutionary adaptations in order to get access to the free food and shelter humans provide. Not just putting up (barely) with humans, but also learning to tolerate each other.

After all, cats’ nearest genetic cousins, African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica) are notably friendly, despite being solitary creatures in the wild. To this day, African wildcats will enter villages and be found around humans. But learning to live in close proximity to other cats apparently necessitated developing a whole repertoire of facial expressions.

According to Florkiewicz and lead author Lauren Scott, a medical student from the University of Kansas Medical Center with a personal interest in cats, domestication allows more cat-to-cat social interactions, which is why the pair believed they would show more expression.

To collect data, Scott filmed 53 cats at a local cat café when both were based at University of California, Los Angeles, between August 2021 and June 2022. From the 194 minutes of video footage gathered, she recorded 186 feline interactions. The cats were adult domestic shorthairs of both sexes, all neutered or spayed.

Both researchers assessed the differences in expression with a coding system designed specifically for cats, called the cat Facial Action Coding System, and looking at the number and types of facial muscle movements. The study added that muscle movements associated with biological processes such as breathing and yawning were not included.

While they were not able to attribute a meaning to each expression they recorded, Florkiewicz and Scott found that 45.7 per cent of coded expressions were friendly, while 37 per cent were aggressive.

4029News

Ears and whiskers forward, with eyes closed, for instance, are friendly expressions. Perhaps unsurprisingly, constricted pupils, ears flattened against the head and a tongue-swipe of the lip are very much not.

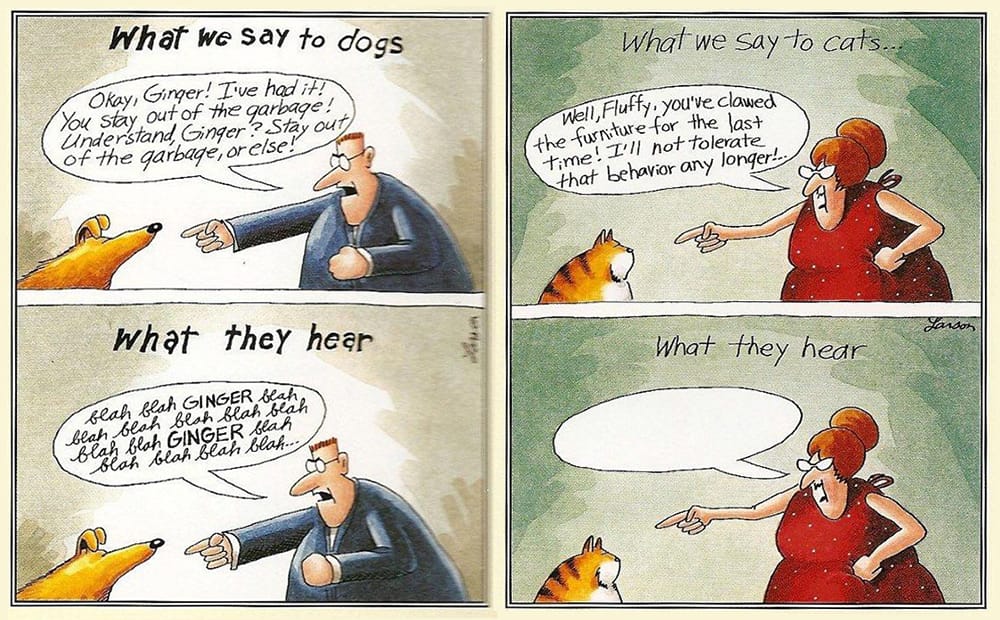

But cats’ evolutionary adaptations go even further. Contrary to Gary Larson’s famous cartoon, cats do indeed hear and understand at least some of what humans are saying to them.

They can use human pointing cues and gaze cues to find food. They also discriminate between human facial expressions and attentional states, and identify their owner’s voice.

Furthermore, cats match their owner’s voice and face when tested with their owner’s photo presented on a screen, and human emotional sounds and expressions.

The evidence is rather tentative, but tantalising. Dr Saho Takagi from Kyoto University, Azabu University and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and colleagues tested cats’ reactions to photos of familiar faces, paired with spoken names.

Half of the trials were in a condition where the name and face matched, and half were in an incongruent (mismatch) condition.

The results of the first experiment showed that household cats paid attention to the monitor for longer in the incongruent condition, suggesting an expectancy violation effect; however, café cats did not.

In the second experiment, cats living in larger human families were found to look at the monitor for increasingly longer durations in the incongruent condition.

Furthermore, this tendency was stronger among cats that had lived with their human family for a longer time, although we could not rule out an effect of age.

Sci News

The experiments suggest that cats raised in mostly human company, rather than with large groups of other cats, learned to associate names and faces. Looking at the monitor for longer in the incongruent condition suggests that the cats may be puzzled by the mis-match: ‘Wait, that’s not Mr Fluffykins…’

As to why cats living in cat café conditions did not show the same results, one possible explanation might be that cats living in mostly feline societies used other, non-verbal cues (such as scent) to recognise each other.