Table of Contents

You can purchase Nieuw Zeeland An English-Speaking Polynesian Country With A Dutch Name: A Humorous History of New Zealand by Geoffrey Corfield from Amazon today.

Christchurch 1850

Christchurch was founded to be a colony in New Zealand (“the most Church of England country in the world”), as a partnership between The New Zealand Company and the Canterbury Association (53 subscribing members including 16 Members of Parliament, 14 Peers of the Realm, seven Bishops, four Baronets, two Archbishops, and a parish priest in a pear tree, 1847).

It was to be a planned not a haphazard town, peopled by ladies and gentlemen colonists who could afford its lofty land prices, and industrious labourers who couldn’t and so had to labour industriously. But they would be granted assisted passage provided they were under 40 years of age and had a certificate of good standing from their parish priest that stated that “the applicant is sober, industrious and honest, and he and all his family are amongst the most respectable of their class in the parish and only ever enter pubs to raise money for the poor”. Seven hundred and seventy-three colonists qualified.

But before the colonists got there, The New Zealand Company surveyor went out to survey a settlement of 1,600 acres preferably at a seaport. Christchurch thus became one of the few British colonies where the surveyors actually beat the settlers. The first spot chosen was not where Christchurch is now (the estuary between the Avon and Heathcote rivers), but Lyttelton Harbour to the south (1849). Unfortunately, although Lyttelton had a harbour and was a seaport, it didn’t have very much flat land; so they made a track along the coast to the east and then around to the north, and the second spot chosen for a town was Sumner.

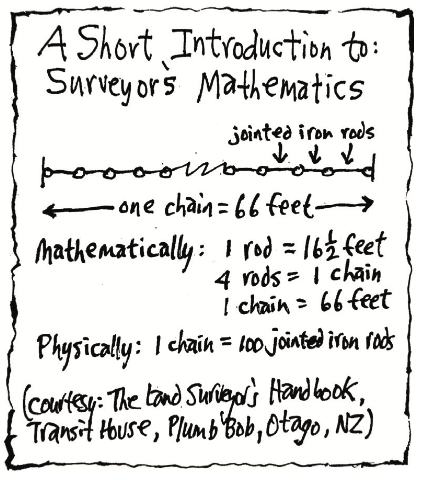

Unfortunately, although Sumner was on the sea, it didn’t have enough flat land either, so they kept going north along the coast until they came to the Estuary, and it looked big enough and flat enough for a town, so they put Christchurch there. Unfortunately, whereas Dunedin was located on a site of high hills, Christchurch was located on a site of low swamps. But roomy, flat, low swamps. So they started surveying. And because The New Zealand Company surveyor did not like streets in a crescent shape (“gingerbread”), or streets wider than 66 feet (except along the Avon River); Christchurch got streets one chain in width laid out in a grid pattern that just went straight through the swamps.

But the first surveys done in Canterbury were not done in Christchurch, but Lyttelton and Sumner. And because Lyttelton and Sumner were surveyed before

Christchurch, they got the first choice of street names before Christchurch. Lyttelton got first choice of street names, Sumner got second choice, and Christchurch got what was left over. Christchurch wasn’t happy. Lyttelton

got streets named Bridle Path, London and Dublin, and a whole bunch of others named after towns in the south of England. Sumner got streets named The Esplanade and a whole bunch of others named after prominent people (Nayland, Wiggins, Dryden, Colenso, Hardwicke, Menzies, Head, Wakefield).

There were hardly any names left for Christchurch to choose from. They had to be content with the scrapings from the bottom of the barrel. But they did remarkably well considering the slim pickings available to them. They chose streets named after other places in the world (Barbados, Madras, Colombo, Montreal); streets named after other towns in Britain not taken by Lyttelton (Manchester, Durham, Armagh, Hereford, Lichfield, Worcester, Gloucester, Salisbury); and streets with names that nobody in their right mind could think of if they tried (St. Asaph, Tuam, Papanui, One Way).

But the first thing these 773 new approved colonists do is not name streets, it’s build churches. By 1856 Christchurch has as many churches as hotels, a rare achievement in a British colonial town.

The idea of Christchurch, however, could not last. Although they were worshiping in a swamp, Christchurch was also sitting on the edge of some of the best agricultural land in New Zealand (the Canterbury Plain, the largest single area of flat land in the country). The plan to sell the swamp land at a high price fails, as little land is sold. Then squatters arrive from Australia, leaving behind a land of drought to lease pasture land for sheep in a land of rain. By 1855 all the plains have been leased for sheep runs. Christchurch becomes “squatting and barbarism”, with more clergymen than were needed (“here I find neither church nor school nor parsonage, not one sixpence of expenditure for the glory of God”). The New Zealand Company goes bankrupt, and The Canterbury Association is dissolved; but Christchurch is in a good financial situation thanks to the leasing out of land for sheep.

Instead of the small English-style landholdings originally planned, Christchurch becomes a region of large-scale sheep farms, where a small number of landowners own a large amount of land, put managers on their estates, and build huge mansions in town.

The settlers love Christchurch though. By 1874 it has a population of 14,270. They have left behind a dreary Britain with lowering prospects and rising damp, to come to New Zealand and become “shaggy, clear-complexioned, brown and healthy-looking”. The men to wear “exceedingly rowdy hats” (a felt slouch hat); and the women to adopt a fashion of brightly coloured tartan shawls, bonnets with feathers and flowers, ear-rings, gold chains, necklaces and bracelets.

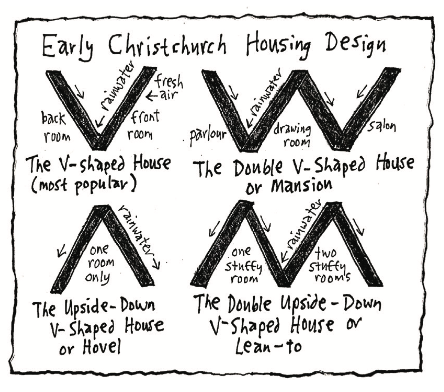

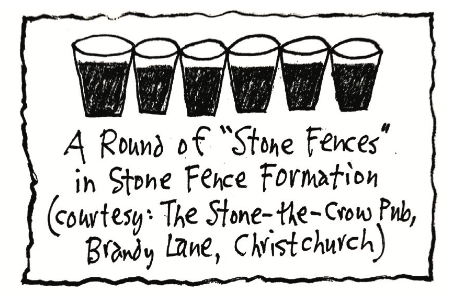

They build V-shaped houses of wood, cob (straw, clay) or wattle and daub (wood frame filled with clay), with thatch or wood shingles; and their favourite drink down the pub is a “stone fence” (brandy and ginger beer, which they drink abundantly).

All is well on the South Island.

You can purchase Nieuw Zeeland An English-Speaking Polynesian Country With A Dutch Name: A Humorous History of New Zealand from Amazon today.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.