Table of Contents

Simon O’Connor

Husband, step-father and longtime student of philosophy and history. Also happen to be a former politician, including chairing New Zealand’s Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Committee.

By now you will have heard of JD Vance, the Republican vice presidential candidate and Donald Trump’s running mate. Much has already been written about him but one particular point caught my attention. It was Vance’s interest in the works of René Girard – a French literary critic, historian, and philosopher. For many readers this may be the first time you have ever heard Girard’s name. He is not particularly well known when compared to some academics but he is a thinker who has had a profound influence on the way I perceive the world. So much so that I did one of my postgraduate degrees exploring his ideas and writings.

I thought, therefore, that I would take an opportunity to simply explain some of Girard’s key concepts both because I have found them insightful and informative in my life, but they will also give a hint at the character and thinking of the likes of JD Vance.

This is a long Substack so important to note that I start simply and then build more and more depth. Put another way, you don’t need to be put off by the length, but at the end is a exposition on how Girard thinks mimetic rivalry can be solved – and also why I think JD Vance is attracted to this philosophy.

TL;DR (TOO LONG; DIDN’T READ)

If you want to reduce Girard’s work to an almost simplistic expression and set of lessons, it is that we are to each take responsibility for our lives; not go about blaming and scapegoating others for when things go wrong for us; for when we do place the blame on others – often destroying their lives – we then go to great lengths to justify what we have done via stories and ultimately set in motion an eventual repeat of the situation.

Here ends the ‘too long, won’t read’ summary! For a bit more depth, continue reading…

WHY DO RENÉ GIRARD’S IDEAS MATTER?

At the heart of Girard’s work, and why it merits attention, is his view of how we as humans relate to one another; why conflict arises and how we deal with it; and why history keeps repeating itself. Girard spent a lot of life reviewing the great literary classics and myths. He noted that a recurring and basic idea within these myths and stories was the use of scapegoats to heal tensions within society and then how the sacrifice of these scapegoats became mythologised in legends, myths, and fables.

For people like me, and I suspect JD Vance, this view of the world means we can own our own faults and imperfections rather than go about blaming others for our woes. It is a philosophy very much at odds with a modern world that spends little time reflecting on the faults within oneself. Identity politics and intersectionality starts from the premise that a person is born perfect – ‘I am who I am’. Anything that goes consequently wrong – or if a person doesn’t get what they want – is to be blamed on others. There is always a scapegoat in the modern world for personal problems – be this colonialism; people of another culture; the government; patriarchy; hierarchy; religious people… the list is endless.

Girard in his writings points us towards examples such as those in the great Greek myths where gods and people were scapegoated – taking on the sins of all and sacrificed accordingly. This is an important observation for it is not enough to place the blame on a scapegoat, but said scapegoat needs to be sacrificed so as to rid the community of its problems.

Other examples include the frequent scapegoating of the Jewish people. Be this during the Black Plague, various pogroms, the Nazis (of course) and, more recently, Islamic regimes and their supporters. During the French revolution, it was the intelligentsia who were blamed for all society’s ills and many were guillotined. One woman in particular – Marie Antoinette – had all that was supposedly wrong in society applied to her, and then killed. If we look at the United States, we can point to the likes of the Salem Witch hunt.

If you wish to apply a Girardian lens on scapegoating to something more contemporary and local, then consider how many New Zealanders responded Covid. With much fear instilled in society, many needed someone to blame – scapegoats to vent frustration upon. One target were Christian churches. Recall how singing hymns was dangerous, supposedly – that they could lead to ‘super-spreader’ events. Singing Christians were putting everyone in danger and media and politicians were keen to make examples of them. As I noted at the time, so great was the threat of singing individuals that churches had to remain closed even while brothels and bars could open!

More generally, the ‘unvaxxed’ were made scapegoats. Their lives were to be sacrificed – jobs lost, isolation from friends and family, no access to businesses, removal from public life and so on. As the prime minister of the time noted, she was happy to have two tiers of people. Girard would talk of such tiers being ‘the community’ and the ‘scapegoat’ – the latter to have all the sins of society placed upon them and then be removed.

DELVING DEEPER INTO DESIRE

What leads to people and society needing scapegoats? Girard says it is desire. It is this desire that Girard is ultimately most keenly focused on in his writing. Why do we desire what we do? Where do desires come from? How do competing desires interact and most importantly how do we reconcile desiring the same things? And how do we explain the conflict and violence we see often in relationships and throughout history?

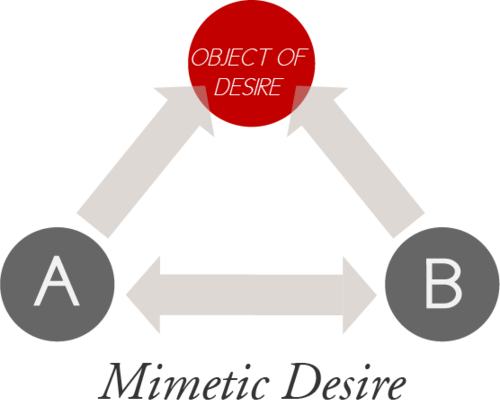

His views on desire are often referred to as mimetic theory and it is quite simple as it is profound. We are human beings that all have desires. We want certain things. We often do things to be desired by others – think of buying a new car to impress others. We might also think of wanting the same object that someone desires. But Girard suggests there is more to human desire for we also want to acquire the same desires of other people; not the object of their desire but the same dynamic of desire. We only need think of the small child that has no interest in an object until its desired by someone else. Or even as adults – we had no interest in the brand of car or clothing until we saw others desiring it. Our focus is not on the object as such – that can change quickly and easily – it is instead each of us imitating the desire of the other person.

This is the heart of Girard’s mimetic theory – that we mimic/imitate the desires of each other. You desire something so now I desire the very same thing and vice versa. Critical to understand is that is not a rivalry based on what the object is per se (e.g., the car or clothing) but a rival desire to another person’s desire. I want to desire in the same way you are desiring. The object of our desire can change, but I will still mimic you (and you me) as our desires are interlinked.

As you might anticipate, this leads to conflict. If individuals or communities are desiring the same things, then rivalry develops and yet, paradoxically, we are simultaneously united in our mutual desire. So with our desires mimicking each other, we find ourselves in conflict and yet needing each other. My desire remains dependent on your desire, even though it is putting us into conflict, and so we need to find someone else to blame for the tensions. I am not gone to blame myself and if I blame my rival, then I am also implicitly blaming myself. Again, our desires are intertwined.

Enter the scapegoat – a person or group to put all the blame for our unrequited desires.

Upon the scapegoat is all the blame for the rivalry and the tension put; they are the reason that we are having problems. As we cannot blame each other for our problems, we blame an outsider. Eventually the scapegoat is sacrificed and in doing so restoring the relationship between the rivals. All the issues are placed on this scapegoat and in excising them, we excise the supposed source of all the problems. Importantly to Girard, this sacrifice needs to be mythologised into stories to explain how the removing of this person or group helped restore balance in the community. The sacrifice – often violent – needs to be justified.

DIVING INTO THE DEPTHS

For those keen to go deeper, and understand a bit more of Girard, I have written more below. Some of it repeats ideas above, but it starts with Girard’s idea of desire; how this becomes something called ‘monstrous doubling’, the process of scapegoating; and finally the creating of myths to justify all that has happened.

We all have desires. Why we desire things, and how we choose to act upon desire, have been questions pondered since the ancient Greeks. Both Plato and Aristotle wrote that artists desired to represent nature and that they did so through imitation; that human art was simply an imitation of nature. Taken further, it was understood that all human desires are the consequence of imitation; that people learn how to speak and behave by copying others. This mimicking of others’ desires came to be known as mimesis, or mimetic desire. The Greeks and later thinkers thought that this mimicking of human behaviour was the full extent of mimesis.

We are probably mostly familiar with linear desire – Jack sees a pair of sunglasses and desires them. The philosopher Hegel’s position is that we ‘desire for the desire of the Other’ – that is, Jack wants the sunglasses so that others will desire him. In contrast, Girard’s position is stated as our desire mimics that of the Other; we see that Jack wants a particular pair of sunglasses and we now also desire them. This desiring is not a convergence on the same object per se, but rather a rival desire for what an Other has already desired.

We mimic the desire and set about a rivalry focused on an object, but based on each other’s desiring.

From these beginnings, Girard’s mimetic theory develops into an explanation of the origins of human conflict and violence. When one person imitates the desire of another for the same object, a rivalry begins. His theory suggests that human conflict eventually leads rivals to mimic each other; what Girard terms monstrous doubling. Despite rivals competing for the same object of desire, they are in fact united by the commonality of that desire. As conflict intensifies, rivals begin to mimic the actions of each other so as not to be outdone. Eventually, the escalation of mimetic rivalry leads to violence yet not between the rivals. As their actions have become so alike, it would be inconceivable for either to harm the other; to inflict violence on a rival would be akin to inflicting violence on one’s self. A third party must therefore, be found onto whom the blame for the conflict can be placed – a scapegoat. Once blame is attributed to the scapegoat, that person must be removed from the group at large in order to restore peace; the sacrifice of the scapegoat becomes a necessary action so that the community can restore harmony. Once expelled from a community, rivals create rituals and stories that both evoke the memory of original sacrifice and, importantly, celebrate the peace that was found as a consequence of that violence.

The victim of the scapegoating therefore, must be both unimportant enough to be sacrificed, yet closely enough identified with the community so that they can represent that community. This is reinforced by the fact that in mimetic rivalry's doubling process, all antagonists will eventually act in unison and therefore, the removal of just one representative group, the scapegoat, is able to purge the problem for all. Ultimately, a scapegoat must be both foreign and familiar. The scapegoat therefore, is both victim and antidote to the cycle of human violence. The peace that comes once the scapegoat has been expelled 'proves' to the community that the scapegoat was indeed the cause of the original strife and therefore absolves the actual antagonists of any blame. Importantly, any act of violence against the scapegoat is not seen as the cause of the ensuing peace but rather that the scapegoat was the obstacle to that peace. To accept that the community's violence lead to peace would be an unacceptable admission of complicity.

One literary example is from Dostoevsky’s wonderful novel, Crime and Punishment. In the novel, the main character – Raskolnikov – illustrates all the realities of Girard’s mimetic theory – the mutual desire, the need to blame, the ensuing act of violence and the construction of myths to justify and explain the preceding actions.

IS THERE ANY WAY OUT?

Girard takes a particularly Christian viewpoint on this question, looking to the person of Jesus Christ. This develops two interesting perspectives.

But before that, we can simply suggest that by understanding mimetic rivalry – and how our desire works – means we can be more self-aware. Instead of seeking to blame others or find scapegoats, we can perhaps take some responsibility ourselves. We can also be aware of how we create stories and myths to justify our actions thereby obscuring the real reasons, increasing the chances of history repeating. Again, by understanding Girardian ideas, we can have our eyes open a bit wider and prevent ourselves falling into the dynamics that have repeated throughout history and our literary traditions.

I noted however that Girard was impressed by the person of Jesus Christ and the stories around him. René was a Roman Catholic after all – as too JD Vance and me. His first observation is that Christ on the cross was the scapegoat, but a scapegoat that did not seek revenge. As the Jewish and Roman authorities mimicked each other’s desire for power and influence, they needed someone to blame and release the pressure between them. As the Gospel stories explain, while enemies, both Jewish and Roman leaders agreed to kill this trouble maker and ‘King of the Jews’. Despite Christ’s scapegoating and death, his followers were urged not to seek revenge. For Girard, this showed how to end the cycle of mimetic violence – forgiveness.

JD Vance actually captures the second aspect of Girard’s solution when he wrote in a magazine article: “Christ is the scapegoat who reveals our imperfections, and forces us to look at our own flaws rather than blame our society’s chosen victims.” The basic premise here relies on the belief that Jesus was perfect; without fault; and blameless. He therefore could not – and should not - be a scapegoat and yet was still killed, highlighting the horrific violence in society and forcing us to confront the reality of our own choices. Put another way, it is easy to place blame on a scapegoat if they have some fault we can identify – but impossible if they are sinless.

Christ’s death puts on full display that scapegoats are usually innocent, and that a community’s violence is wrong and unjustified.

In concluding, there is of course so much more to René Girard’s thought. There are lots of nuances and much that I have not been able to explore here. The intention remains to have given readers a small insight into what influences both the thinking and actions of the likes of JD Vance but also myself, as well as perhaps to whet some people’s appetite to learn more about Girard. I would recommend his book Violence and the Sacred as a good starting point, along with The Girard Reader, edited by James Williams.

For those interested in a more theological and anthropological discussion, check out James Alison’s book, The Joy of Being Wrong.

... arcadias, utopias, our dear old bag of a democracy, are alike founded:

For without a cement of blood (it must be human,

it must be innocent)

no secular wall will safely stand.

- W H Auden. Vespers, from Horae Canonicae.

This article was originally published by On Point NZ.