Table of Contents

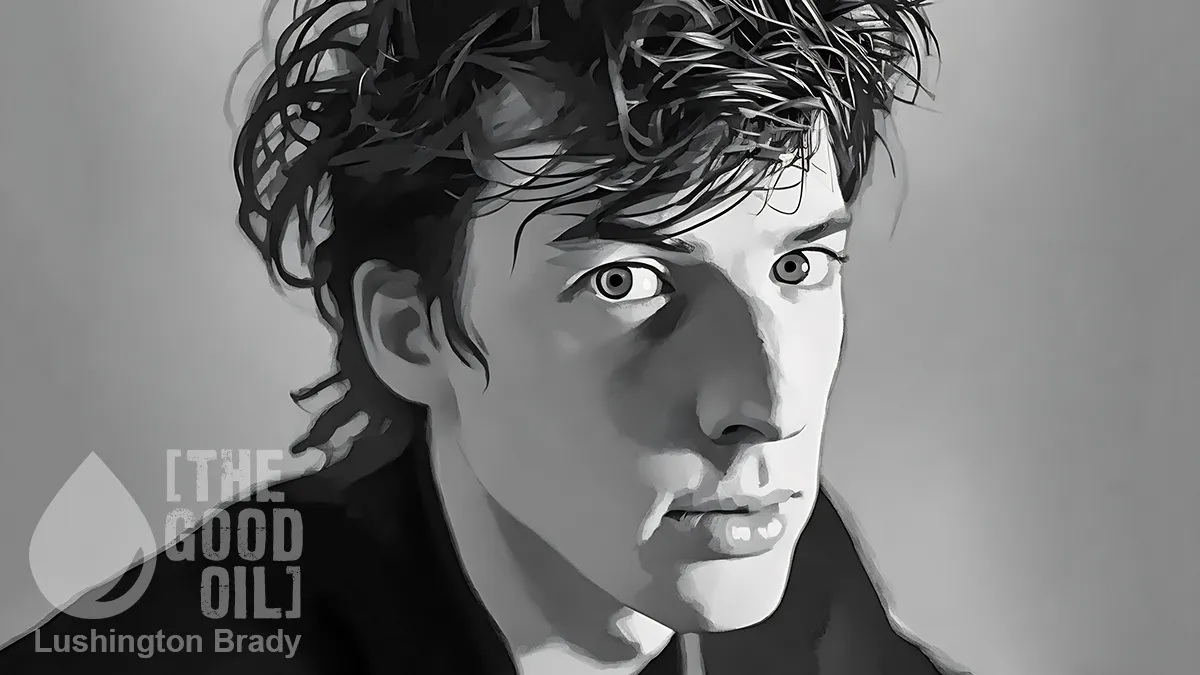

It’s famously said that, maybe only 1600 people originally bought The Velvet Underground and Nico, but every one of them went out and formed a band. One person who certainly did just that was a Jewish boy from Boston named Jonathan Richman. Over the next 55 years, he carved out a unique if too-often obscure niche for himself in the under-strata of popular music.

It seems that the world is divided into people who barely know of Jonathan Richmand and devoted fans. Most people would be at least vaguely familiar with Richman as the troubadour-like ‘Greek chorus’ of the Farrelly Brothers’ 1998 hit comedy There’s Something About Mary. Everyone who was a child or a parent at a certain time would likely be familiar with his song, “I’m a Little Airplane”.

Jonathan Michael Richman was born in Boston in 1951. Those two biographical facts – New England and being an adolescent in the mid-60s – have formed the backbone of much of his creative output, with songs like “I Love New England” and “Parties in the USA”. But it was an early infatuation with the Velvet Underground (whom he later lionised in song) that kick-started his musical career. In 1969, he moved to New York, living on Velvet’s manager Steve Sesnick’s couch and trying to break into music.

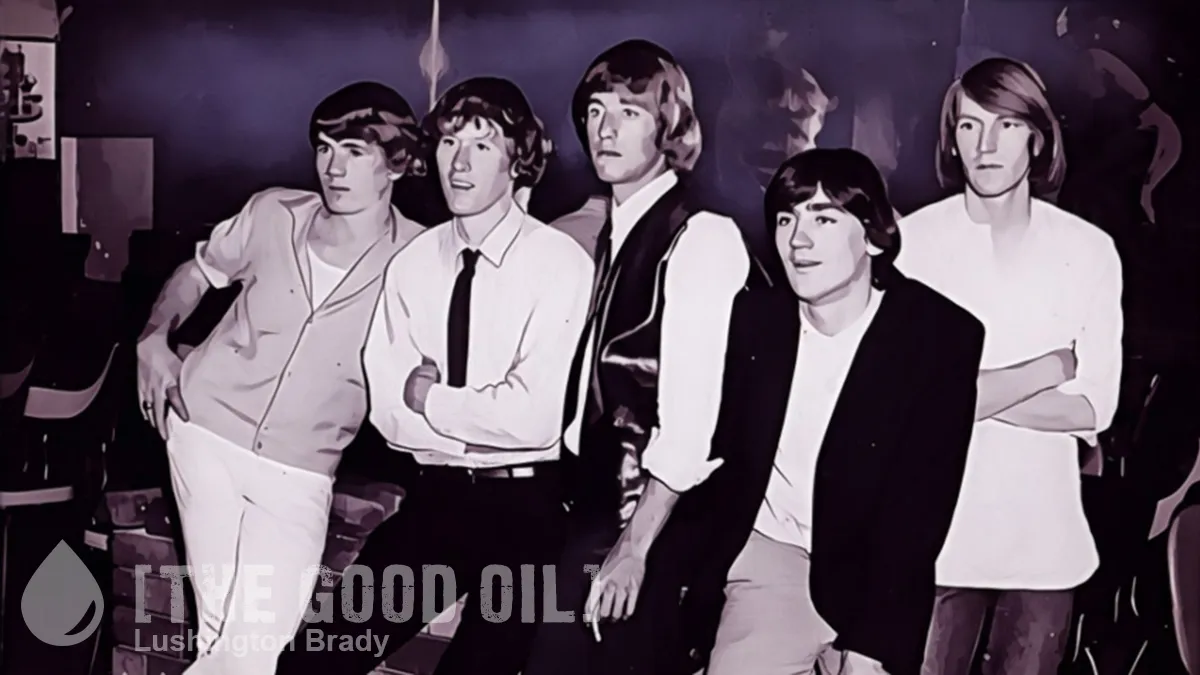

Failing to find success in New York, Richman returned to Boston after a year, and formed the band that would first make his name among the musical cognoscenti: the Modern Lovers. Members of the original lineup of the Modern Lovers included Jerry Harrison (later of Talking Heads) and David Robinson (later of the Cars). The band recorded demos with John Cale (the Velvet Underground) and Kim Fowley (manager of the Runaways). But the band struggled to secure a recording contract and by the time both were released as albums the original Modern Lovers had broken up and Richman had undergone a distinct change in direction.

But The Modern Lovers album went on to have much the same far-reaching influence as The Velvet Underground & Nico. Released in 1976, when glam and prog rock were at their height, The Modern Lovers by contrast featured stripped-down, three-chord, amped-up rock’n’roll, which, in 1976, was exactly what the emerging punk scene was looking for.

As a consequence, songs like “Roadrunner” and “Pablo Picasso” (which re-imagines the great artist as a ‘Big Man on Campus’ hipster picking up girls while “he would drive down their street in his El Dorado”) became proto-punk classics. The Sex Pistols and Joan Jett both recorded versions of “Road Runner”. John Cale and David Bowie separately recorded covers of “Pablo Picasso”, while Siouxsie and the Banshees and Echo and the Bunnymen each covered “She Cracked”. Other artists who’ve cited Richman as an influence include Violent Femmes, They Might Be Giants, Weezer, the Pixies and many more.

Yet, even before The Modern Lovers was released, Richman had decidedly moved on, to a sound and style that would become his mainstay for the next half-century. That sound and style is characterised by a more laid-back and mellow musical approach, with a semi-staccato Fender guitar twang combining elements of rock’n’roll, Latin and Reggae. His lyrics exhibit a disarming, childlike honesty and wonder and a sometimes almost stream-of-consciousness flow of words. Indeed, Richman once said, “I don’t write, really. I just make up songs.”

But whether it’s the simple joy of kids running around a park pretending to be aeroplanes, “dancing in the lesbian bar” or celebrating the magic of “When Harpo Played His Harp”, Richman never gives off an air of anything less than open sincerity.

Little wonder, then, that the Farrelly Brothers, also from New England, felt that Richman’s sporadic appearances, as a kind of Greek chorus, would form a charming, whimsical counterbalance to the crude humour and slapstick of There’s Something About Mary. Peter Farrelly says that the positive, sometimes naive, worldview of Richman’s music deeply moved him. “That Summer Feeling”, as Richman sang.

“7up on a hot day, and the smell of bubblegum, and it was these dark, mysterious little places where they knew you… these hot lazy afternoons, where you’d ride your bike, and in silence. No one had anything… and you spent most of your time outside! After dinner, everyone played – there were no fences” – Jonathan Richman

Richman’s self-description of his first essays at public performances could easily characterise his entire career: “I first started playing these songs out in public in March of 1968. Just coffee shops, outside, anywhere anyone would let me play… [people] were pretty amazed. And they ran. They knew when the gettin’ was good, so they just ran out… people by the hundreds would run away with their hands over their ears. Well , 200 stayed! And I was thinking, all right! Some people actually stayed!”

As, over the next few decades, Richman released a steady stream of albums, his amazement that people stayed never seemed to go away. I once read a social media post where a fan described going up to him after a show and telling him how much he enjoyed it. Richman’s face, he said, lit up. There was no cynicism or phoniness: he just seemed genuinely pleased and touched that someone enjoyed the show.

While the Modern Lovers became a rotating backing band, from 1988 he mostly performed as a solo act. Key albums (although there’s no such thing as a bad Jonathan Richman album) include Jonathan Goes Country, Having A Party With Jonathan Richman, You Must Ask The Heart, I, Jonathan and Surrender To Jonathan. He has also released a number of Spanish-language albums, ¡Jonathan, Te Vas a Emocionar! and ¿A Qué Venimos Sino A Caer?, and the Latin/World Music-influenced Ishkode! Ishkode!

From the 2000s, his work became more and more poetic. “Poetry, if you love it,” he says, “it works its way into your conversations and into anything you do.” His most recent album, Only Frozen Sky Anyway, released last month, is perhaps his most explicitly poetic yet. While the album contains Richman’s trademark whimsical humour, with songs like “But We Might Try Weird Stuff”, it’s plain that, in his mid-70s and with many of his peers popping their clogs, intimations of eternity are coming to the fore. “That Older Girl” is an old man looking back on awkward first crushes with a mix of longing and acceptance. The album closes with the magnificent melancholy of “The Wavelet/I Am the Sky”:

Oh, this wavelet has been tossed from shore to shore, rested a while, then come back for more. Come home little wavelet, you can sleep in my cradle, cradle of calm eternal. But I don’t want to go to sleep now, I want to dance. Oh, come home, little wavelet, we won’t turn off your star, and you can dance with me on the banks of the far shore.