Table of Contents

Dan ‘Danny Sexbang’ Avidan, one half of comedy rock band Ninja Sex Party, says that it was hearing Flight of the Conchords that made him realise comedic groups could also write really good songs, which suggests he’d never listened to the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band.

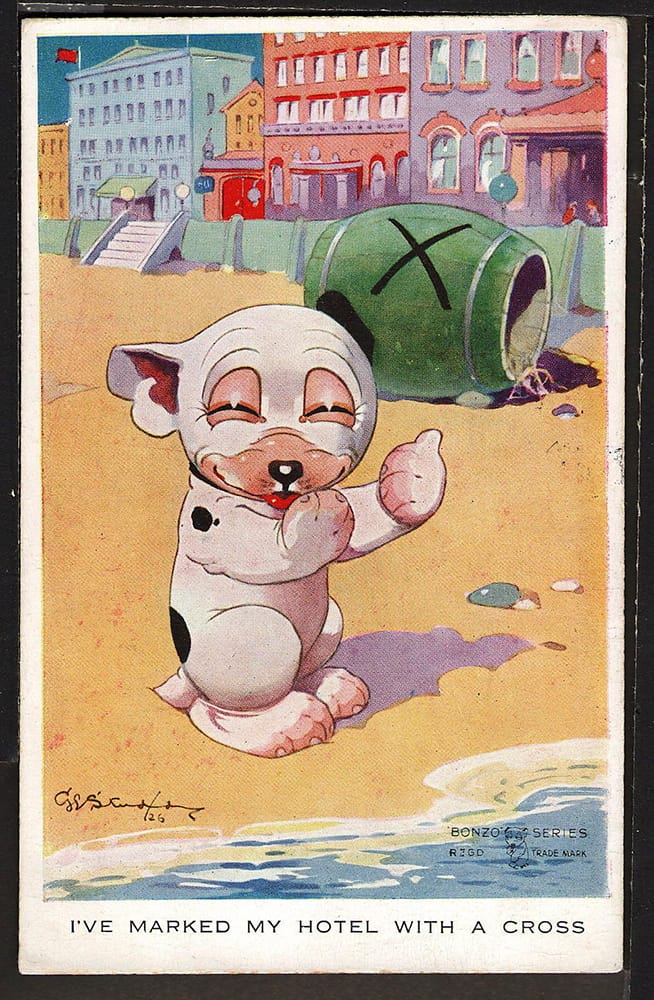

Like New Zealand’s Split Enz, the Bonzos formed as an art school cabaret comedy band one decade earlier and on the other side of the world. The Bonzos formed in 1962 at West Dulwich in London, where founding members Vivian Stanshall and Rodney Slater met while watching a late-night broadcast of the Sonny Liston-Floyd Patterson heavyweight championship fight. The two discovered a shared love of early 20th-century jazz and Dadaist humour: the group’s original name was the ‘The Bonzo Dog Dada Band’ (drawn from cartoonist George Studdy’s Bonzo the Dog, which the band adopted as a mascot).

Over the next decade, the Bonzos would carve out a unique, if often obscure, niche in the British musical landscape: irreverent, experimental and defiantly unclassifiable. Although they only had one hit – “I’m the Urban Spaceman”, which reached number five on the UK charts – their influence was felt by more famous artists, from Monty Python, the Beatles and David Bowie, to Death Cab for Cutie (who took their name from the Bonzo’s song, which was featured in the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour film).

The Bonzos were consummate outsiders – too eccentric for the mainstream but too brilliant to be ignored.

Initially, the band focused on reviving 1920s jazz with a comedic twist, performing songs with kazoos, washboards and a gleeful disregard for musical propriety. Like Australia’s later Captain Matchbox Whoopee Band, their repertoire included original compositions and revivals of long-forgotten hits from the 1920s, like “Jollity Farm” (a rendition of which would much later see Fred Negro and Phil Grizzly, of notorious Melbourne punk band I Spit On Your Gravy, win Hey, Hey, It’s Saturday’s ‘Red Faces’ segment). However, as the cultural climate of the 1960s shifted, so too did the band’s style. They began to incorporate rock and psychedelic elements, adapting their sound to mirror and mock the musical trends of the time.

The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s most famous moment came in 1968 with the release of “I’m the Urban Spaceman”, a novelty hit produced by Paul McCartney (under the pseudonym Apollo C Vermouth). The song, a whimsical and satirical take on space-age cool was a brief brush with mainstream success, but one that captured the band’s essence – clever, catchy and absurdly tongue-in-cheek.

Their chart success was all-too-fleeting, though, as the Bonzos refused to follow a conventional pop trajectory. Their albums, such as Gorilla, The Doughnut in Granny’s Greenhouse and Tadpoles, featured often catchy songs and brilliant musicianship, but veered through such a bewildering array of styles and moods that mainstream audiences were simply too baffled. A catchy, rock-heavy song like “Mr Apollo” might be followed up by the weirdly surreal “My Pink Half of the Drainpipe” or the rocking-but-surreal “We Are Normal”.

What set the Bonzos apart from other comedic or novelty acts was the intellectual rigor behind their absurdity. Their satire was sharp and often prescient. In mocking the tropes of popular music – whether the bombast of psychedelia or the faux authenticity of blues rock – they exposed the artifice of the industry. Vivian Stanshall, in particular, brought a poetic and often dark sensibility to the band’s lyrics, exploring themes of identity, conformity and Britishness with a distinctly baroque flair.

Their work also bridged the gap between music and performance art. Live shows were theatrical spectacles filled with costume changes, absurd props and onstage antics. These performances were not just about music, but about challenging the very notion of what a band could be. In many ways, the Bonzos anticipated the multimedia performances of later avant-garde and alternative acts, from the Enz, to the Tubes or Klaus Nomi.

Beyond music, the Bonzos’ influence had a profound impact on British comedy in the ’60s – especially the most famous comedy troupe of the era, Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Members of the group collaborated closely with the Monty Python team, and Neil Innes – one of the band’s most musically gifted members – became a frequent Python collaborator, even earning the nickname “the seventh Python”. Innes not only worked with Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin in the pre-Python Do Not Adjust Your Set, but appeared in multiple roles in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, most notably as the leader of Sir Robin’s minstrels. He contributed the signature songs, “Knights of the Round Table” and “Brave Sir Robin”. Innes would go on to create the Rutles, a Beatles parody band that blurred the line between satire and tribute.

Moreover, the Bonzos’ genre-defying approach inspired countless artists in the punk and post-punk eras, many of whom cited the band as an influence. Their irreverence, DIY ethos and embrace of the absurd found echoes in bands like Devo, the Residents and even Talking Heads. In the UK, groups like Madness and Blur carried forward the Bonzos’ legacy of combining pop with performance and irony.

Try getting away this these days. The Good Oil.

The original run of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band was relatively brief. Internal tensions, the pressures of the music industry and Stanshall’s increasing struggles with mental health and substance abuse led to the band’s dissolution in 1970. Several members went on to other projects – Innes with the Rutles and various solo efforts and Stanshall with his cult classic Sir Henry at Rawlinson End, a surreal spoken-word epic that expanded on the Bonzos’ theatricality.

Stanshall died in 1995. A memorial plaque was unveiled in the Poets’ Corner at Golders Green Crematorium on 13 December 2015, opposite that of his friend Keith Moon. After some legal wrangling (mostly determining that no one else wanted them), his son Rupert received boxes of hours of never-released material that was eventually released as two albums. Stanshall is also represented on a public artwork, the Blackpool Comedy Carpet, which commemorates more than 1000 selected influential comics.

The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band may never have sold millions of records or headlined festivals, but their contribution to music and culture is undeniable. If you want a good intro to the Bonzos’ eclectic catalogue, I suggest starting with their 1974 double-album compilation, The History of the Bonzos.