Table of Contents

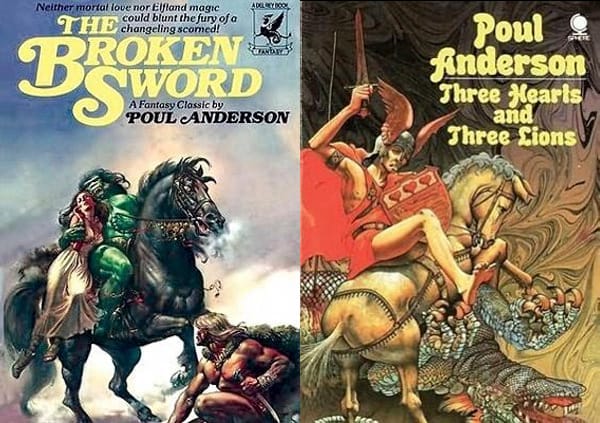

For modern fantasy literature, 1953 was the annus mirabilis. It was, of course, famously the year that J R R Tolkien published the first volume of The Lord of the Rings. While Tolkien’s famous epic is justly described by scholars such as Tom Shippey as establishing the modern fantasy genre as we know it, in its shadow live two novels published or begun in the same year that are just as revered by cognoscenti, even while they remain largely unknown: Danish-American author Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword and Three Hearts and Three Lions.

Like Tolkien’s legendarium, Anderson’s fantasy works are steeped in northern mythology. But, where Tolkien’s is the world of Beowulf, when the pagan invaders of England were being transformed by Christianity, Anderson’s world is darker, older and thoroughly Norse-Germanic pagan.

Anderson was perhaps better known as a science fiction writer: He won the Hugo Award seven times and the Nebula Award three times, and was nominated for both many more times. But it was his fantasy work that establishes him as one of the most versatile and historically conscious writers in 20th-century American speculative fiction. Born in the United States in 1926, he spent part of his childhood in his parents’ native Denmark, returning to the US at the outbreak of WWII.

Though he was born in the United States, Anderson carried his Danish heritage not as an abstract label but as a living framework of myths, sagas, humour and national temperament. His works demonstrate not only knowledge of Scandinavian languages but an immersion in the ethical codes and imaginative landscapes of Viking-age literature. These influences permeate his character archetypes, narrative structures, cosmologies and prose rhythms. Anderson’s fantasy is not simply Tolkienesque, although he anticipated or paralleled Tolkien in many respects, but profoundly Nordic, in a way few American writers have matched.

As a fantasy writer, he bridged the gap between mythic antiquity and modern narrative craft, fusing scholarly rigor with a swashbuckling sense of adventure. Anderson’s two classic fantasy novels are for many readers the purest expression of his literary identity. They combine heroic romance, philological precision and a deep fascination with Northern European, and especially Danish, cultural memory.

Tolkien, as a deeply Christian writer, celebrated the eucatastrophe (a term of his own coinage): “the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly the good catastrophe…it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur”. For Tolkien, “the Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation.”

It’s not all fairy-tale happy endings, of course. Eucatastrophe, Tolkien also wrote, “does not deny the existence of dyscatastophe, of sorrow and failure”. But Tolkien was at heart an Anglo-Saxon, a people who came of age in the 10th century: the ‘Iron Century’, but one where the promise of Christianity held out a hope that leavened the fatalism of the northern imagination

But, in the pagan mindset of Anderson’s fantasy, a pre-Christian world, all is sorrow and failure. This was a world, as Roger Lancelyn Green wrote, where, “even when there were no wild beasts and wilder men to fight, it seemed that the very elements were giants who fought against them with wind, frost and snow as weapons”.

“It was a cruel world,” Green says. But one where “there were mighty deeds to be done”. The cruelty, despair, courage and heroism of the northern world all come together in The Broken Sword.

The basic plot of The Broken Sword is the story of Skafloc, a changeling (a human baby secretly stolen by elves and exchanged for one of their own). Skafloc is the son of Orm, a pagan Viking in the Danelaw of Dark Ages England, who marries Aelfrida, an Anglo-Saxon woman. After killing a witch’s family to take their land, Orm later half-converts to Christianity but quarrels with the local priest and drives him away.

Pursuing revenge, the witch aids elf-king Imric to abduct Orm’s newborn son. In the child’s place, Imric leaves a changeling named Valgard. The real son is taken to the elven lands and raised as Skafloc. As the story progresses, both Skafloc and Valgard play key roles in the war between the trolls and the elves.

The novel traces an inexorable tragic arc: family betrayal, incest revealed too late, and a catastrophic clash of supernatural powers culminating in near-apocalyptic destruction. The titular sword itself, crafted by dwarves and bearing a curse reminiscent of the cursed blades in Norse myth, compels its wielder toward destiny rather than choice, locking the narrative into an implacable fatalism. The story, indeed, has many elements and plot points employed by Tolkien in his The Children of Húrin, the most doom-ridden story he ever wrote.

It’s not a case of plagiarism by either author. While Tolkien wrote the earliest drafts of The Children of Húrin in the 1910s, both writers laboured in ignorance of each other.

Rather, both authors were obviously heavily influenced by the great Nibelungenlied, most famously adapted by Richard Wagner for his epic, doom-laden Ring Cycle. In fact, the very name of the broken sword, Tyrfing, comes from the Hervarar Saga, a 13th century saga composed from much older sagas in Germanic legend. The Hervarar Saga tells how it was made under duress by the dwarves to be a weapon that would never miss, never rust and could cut through iron or stone like cloth. However, the vengeful dwarves also put a curse on the blade, so that it would kill every time it was drawn and would turn on its owner at last.

Both writers also deliberately and masterfully employ muscular, archaic prose. Tolkien, the language style of the Anglo-Saxons, Anderson the stylistic choices of the sagas. Anderson uses kennings, rhythmic phrasing and stark dialogue. Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Broken Sword is unusually compact and intense, with little digression.

The Broken Sword also presents a a very different tonal and mythic structure to The Lord of the Rings. Where Tolkien’s narrative is infused with nostalgia and an overarching moral teleology, Anderson’s world is brutal, tragic and pagan, closer to the eddic and skaldic traditions of Icelandic sagas. There are no hobbits in The Broken Sword – and not much in the way of eucatastrophe, either.

While never as commercially famous as Tolkien, The Broken Sword deeply influenced later fantasy writers. Michael Moorcock famously called it one of the great works of heroic fantasy and a direct inspiration for his own doomed-hero sagas, including Elric of Melniboné and the cursed blade Stormbringer. The novel helped pave the way for a darker, myth-attuned heroic fantasy long before the grimdark subgenre. Crucially, The Broken Sword captures the ethos of Danish and broader Scandinavian heroic legend: bravery is validated not by victory but by standing firm in the face of one’s doom.

Anderson’s fantasy writing took a much lighter tone – at least, by way of comparison – in his other great fantasy work of the same year, Three Hearts and Three Lions. While published as a novel in 1961, it first saw light as a novella in Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine in 1953.

Three Hearts and Three Lions tells the story of Holger Carlsen, an American-trained Danish engineer who is catapulted from a WWII battlefield to a parallel universe where Northern European legend is real. On arrival, Carlsen finds the equipment and horse of a medieval knight waiting for him: they fit him perfectly and he finds he knows how to use them, as well as speak the local language (archaic French). The device on his shield gives the novel its title. Teaming up with Hugi the dwarf and Alianora the swan maiden, Holger sets out on a perilous quest as a champion of Law, fighting dragons, giants, werewolves, trolls and more.

If The Broken Sword channels the pagan north, Three Hearts and Three Lions merges that heritage with Carolingian romance. It is lighter in tone, more humorous and ultimately more optimistic, yet it shares a fascination with the boundary between mythic worlds and human duty. The hero’s twin identities of Holger Carlsen/Ogier the Dane are in fact derived from the legend of Holger Danske, a hero who, like King Arthur, sleeps until the hour of his country’s darkest need.

Anderson’s Danish heritage is not incidental to his work: it is the wellspring of his imagination. In The Broken Sword, it yields a stark tragedy worthy of the Eddas. In Three Hearts and Three Lions, it produces an affable yet profound meditation on heroism, identity, and cultural memory. Across his oeuvre, Anderson gives voice to a distinctly Nordic vision of fantasy, one where beauty and doom intertwine, where heroes strive against darkness with courage and humour and where myth remains alive, potent and deeply human.

The two novels remain touchstones of the genre because they unite scholarly precision with narrative vigour. Anderson did not merely borrow Scandinavian motifs: he lived within them, shaping stories that resonate with the philosophical and mythic depth of the sagas while remaining accessible and engaging to modern readers.