Table of Contents

To most moviegoers, Dario Argento is almost an unknown. Some might recall his 1973 classic, Suspiria, or at least the 2018 remake. To true horror afficionados, though, the Italian director is a legend. To devotees of the macabre, especially those who spent our formative cinema-going years trawling late-night fleapits and poring over lurid VHS box art in the “Foreign Films” section of Blockbuster, Argento is an icon – a name whispered with the same intensity as Hitchcock or Kubrick.

Born in Rome in 1940, Argento began as a film critic and screenwriter, including co-writing Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), before moving into directing at the turn of the 1970s.

His directorial debut, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), is a solid horror-thriller that already featured some of his trademark tropes – the unseen killer, gruesome murders (usually involving knives), elegant camerawork, obsessive formalism and a fixation on perception itself – barely hinted at what was to come. Not to mention badly dubbed English and the inclusion of an American or British ‘star’ to try and broaden the films’ appeal to non-Italian audiences. Said stars were invariably A-listers on the tail-ends of their careers (David Hemmings), or minor and B-list actors (Suzy Kendall, Leigh McCloskey, Anthony Franciosa).

Other key themes emerged in his next films, The Cat o’ Nine Tails (1971) and Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971): notably the elevation of the murders in the stories into philosophical puzzles. Crimes are rarely just crimes in Argento’s films: they are puzzles of sight and sound and distortions of reality, where truth lies buried in a single overlooked image or sound. His protagonists are often artists, writers or musicians – stand-ins for Argento himself – who stumble into mysteries that consume them. The killers, masked and gloved, act out their violence with fetishistic precision.

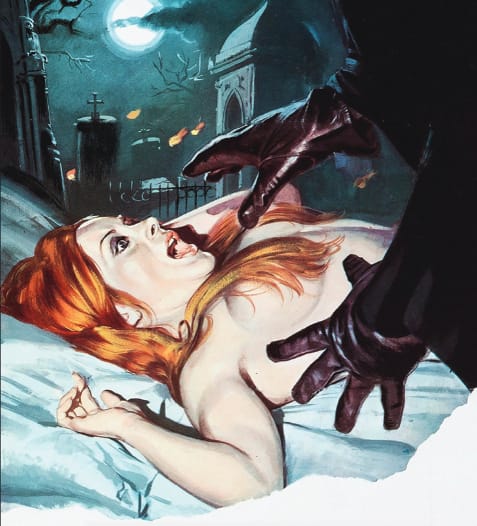

But it was 1975’s Deep Red that unleashed the true Argento artistic vision, a near-poetic take on the Italian giallo genre. Named for the yellow covers of pulp crime novels, giallo is a uniquely Italian hybrid of thriller, mystery and horror. Horror fumetti (comics), such as Terror, Oltretomba and Cimiteria, also fuelled Argento’s take on the horror genre – most especially their use of extreme imagery of sex, horror and saturated colours.

In its cinematic incarnation, giallo is a cinematic cousin to both the American noir genre and the 19th century French Grand-Guignol, a gory stage tradition that relished in grotesque spectacle and baroque violence. But while the Grand-Guignol aimed to shock its Parisian audiences through theatrical exaggeration, giallo transformed murder into visual poetry. Argento would become its most flamboyant poet.

Deep Red solidified his reputation among horror aficionados. A masterclass in suspense and surreal atmosphere, Deep Red took the mechanics of giallo to operatic extremes: a labyrinthine plot laced with Freudian undertones, dazzling set design and a pounding progressive rock score by German group Goblin. Argento turned murder into choreography, a dance of blades and shadows that owed as much to ballet as to brutality. The famous scene of the psychic’s murder, reflected in the gleam of a knife, encapsulates his obsession with the act of seeing: the audience itself becomes complicit, trapped in the act of voyeurism.

Ballet and murderous brutality were central to Argento’s next film and magnum opus, Suspiria (1977), which spirals from a creepy murder-mystery in a girls’ ballet school (lending it a sexual overtone similar to Ken Russell’s 1971 film, The Devils) to a nightmarish black magic conspiracy. Like Russell’s films, too, Suspiria is a whirlwind of astonishing, surreal and often overwhelming sound and vision. Throwing aside the sonic conventions of horror, where suspense is signalled by silence and quiet music, the suspense in Suspiria (and later films) is set to a blaring prog-rock score. Again by Goblin, the soundtrack is a cacophony of whispers, drums and electronic shrieks.

The sensory assault continues in the set design and in cinematographer Luciano Tovoli’s use of Technicolor: all hyper-saturated blues, greens and arterial reds, evoking the palette of fairy tales twisted into horror. As Red Letter Media’s Mike Stoklasa says, Suspiria is one of the most beautiful films ever made. Even when showing such horrors as a knife stabbing into a still-beating heart. Realism has little place in Suspiria, instead the film’s logic is dreamlike and irrational, as if filtered through the subconscious of a terrified child (a theme earlier explored in Deep Red).

Suspiria is less a horror film than a cinematic spell, one that continues to mesmerise audiences nearly 50 years later.

Argento eventually spun Suspiria into a loosely linked trilogy, the ‘Three Mothers’ trilogy, centred around a triumvirate of witches, Mater Suspiriorum, Mater Lachrymarum and Mater Tenebrarum (Latin for, respectively, sighs, tears and darkness).

But if Suspiria was dreamlike and unreal, Argento’s next film, and second in the trilogy, Inferno, dived headlong into surrealism. The plot, following an American student investigating the disappearance of his sister and the death of a friend, both connected from New York to Rome by an old alchemy book, barely makes a lick of sense. Characters dive into elegantly furnished rooms that are, for no discernible reason, filled with water and hot dog vendors randomly run up and stab blind men being torn apart by rats. None of that matters in the least, though: the bizarre imagery is just so weirdly compelling that the viewer just can’t look away.

Tenebrae (1982) is the least satisfying as a sequel, in that the Three Mothers seem to have nothing at all to do with the story of an American novelist in Rome being stalked and harassed by an obsessed fan who is committing a string of murders that appear to be tributes to his work. Again, though, none of that matters in a film that is otherwise both a masterful thriller and an artful meta-commentary on its genre. If nothing else, its opening shot is a masterpiece of sound and imagery, combining the virtuoso camera work of its long, voyeuristic, tracking shot over the façade of an apartment building with Goblin’s driving rock music.

With Tenebrae, Argento arguably reached the end of his dream run as ‘the Italian Hitchcock’, yet his fame remained limited to horror circles. His work was too stylised, too violent and too operatic for mainstream tastes.

But from there, it was a long, slow decline, as his output became uneven, reflecting both changing audience expectations and his own evolving obsessions. Films like Opera (1987) and The Stendhal Syndrome (1996) displayed moments of brilliance – his fascination with art and violence still intact – but lacked the cohesion of his earlier triumphs. Yet even his weaker films possess moments of visual or conceptual genius: a glint of a knife, a cascade of blood that looks like paint or an impossible camera movement that defies logic.

By the time he officially concluded the Three Mothers trilogy, apparently disowning Tenebrae as an instalment, with 2007’s Mother of Tears, his wad was well and truly shot. Apparently learning nothing from Francis Ford Coppola’s widely derided casting of Sofia Coppola in The Godfather III, Argento placed his own daughter, Asia Argento, in a film that is one of the most poorly rated of his career.

Still, few directors have had quite so remarkable a career behind them. Argento had already cemented his enduring mystique for horror cognoscenti, with his refusal to cater to conventional narrative or moral expectations and bringing an entirely new aesthetic – the appreciation of aesthetics itself – to the genre. His cinema is less about what happens than how it happens – the texture of light, the rhythm of sound, the geometry of fear. He treats horror not as a genre but as an art form, as legitimate as any avant-garde experiment.

This approach, however, has also been the source of his relative obscurity outside the horror community. Argento’s films defy translation into mainstream sensibility. They are too stylised to be naturalistic thrillers, too gory to be art-house and too abstract to be mere pulp. In an era when horror is increasingly psychological or ironic, his work feels unapologetically sincere and drenched in operatic emotion.

And yet, Argento’s fingerprints are everywhere. His influence can be traced through the formal precision and baroque violence of Brian De Palma (especially Phantom of the Paradise, Carrie, Dressed to Kill and The Untouchables) to the neon nightmares of Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive, Bronson). Even contemporary horror’s renewed fascination with the aesthetics of colour and sound – seen in films like Panos Cosmatos’ Mandy (2018) and Refn’s The Neon Demon (2016) – owes an unmistakable debt to Argento’s visual bravura.

Dario Argento remains, then, both legend and ghost: a director whose name may never ring familiar in multiplexes, but whose spirit haunts the medium itself. Like the killers who glide through his films, he leaves traces – reflections, shadows, fragments of a vision – that linger long after the screen fades to black. To those who seek beauty in terror and terror in beauty, Argento is not merely a director. He is a conjurer of nightmares, a painter in blood: the high priest of cinema’s dark cathedral.