Table of Contents

A week before election day, TVNZ’s John Campbell went to a polling station in Otara, South Auckland, to lie in wait for voters. When he encountered a young Maori woman who was about to vote for the first time, his trademark gushiness was unleashed:

“Mere is nineteen. She speaks fluent te reo Maori and English. She’s one of those young people whose sense of self sparkles. Her bilingualism must be such an affront to those of us so insecure we paint out the word ‘rapihi’ on a rubbish bin. That strange, mean, brittle fear, that makes being enriched feel like being diminished.”

Who knew that the Maori word for “rubbish” appearing on a bin was “enriching”? Or that speaking a language other than English could invest a young person with such virtue? And who is going to be cruel enough to break the news to the hyperventilating Campbell that Mere is just one of more than a million New Zealanders who can understand a language other than English? Is each of them equally praiseworthy on account of their bilingualism (or perhaps tri-lingualism or more)? And do they “enrich” us just as much by their linguistic prowess as Campbell seems to think Mere does?

According to the 2018 Census, New Zealand had 4,482,135 speakers of English, with te reo Maori a far-distant second at 185,955. Among the top 25 languages spoken in New Zealand, there were also 101,937 Samoan speakers, 95,253 who spoke Northern Chinese (Mandarin), with 69,471 speaking Hindi. Some 55,116 spoke French, 43,278 Tagalog, 41,385 German, and 23,343 Dutch. The list includes 22,986 who can communicate in New Zealand Sign Language. But it is te reo Maori alone that excites admiration and excitement among the chattering classes that often lurches towards liturgical levels of reverence and praise.

As AUT’s Professor Paul Moon put it in his 2018 book Killing Te Reo Maori: An Indigenous Language Facing Extinction:

“References to the language itself are reverential and devotional, with an emphasis on the unquestioned sanctity of te reo Maori; there is the well-worn narrative of a long struggle over obstacles to ensure te reo Maori’s survival; and at the end, by adhering to whatever incarnation of the tenets of revitalisation are being preached, there is the promise of redemption.”

Yet, while te reo speakers are lionised, the truth is that it is immigrants who can speak only limited English when they arrive here who are our true language heroes. From a viewpoint of communication, learning te reo is a luxury for nearly everyone who tries to master it. Apart from formal occasions on marae and other ritualised settings, anyone who can’t speak or understand te reo is rarely disadvantaged. English is the mother tongue of practically every New Zealander who is born here — including Maori. The vast bulk of our population speaks English either as a native speaker or as a second language, albeit with various degrees of proficiency. However, when immigrants arrive without a good working knowledge of English (which is often the case for partners and children of the principal applicant), they are at a real disadvantage until they master it. They will typically struggle to communicate successfully in English in everyday scenarios such as shopping, banking and taking public transport. They also won’t understand what vital information English-speaking doctors, real estate agents and lawyers are telling them. And that disadvantage often continues.

I have an Iranian friend whose first language is Farsi. She speaks English well but after many years here she still sometimes needs help deciphering official documents and medical advice — if only to check she has understood exactly what is meant. She and other immigrants are the truly admirable linguists in our multicultural society — they have to master English as quickly as possible to survive in a country in which English is the only lingua franca. They have little choice.

We also rarely hear extravagant praise for a Chinese immigrant, say, for being fluent in both Mandarin and English — let alone casting their bilingual ability as a reproach to those who aren’t as linguistically capable. On TVNZ’s Q&A on Sunday when Campbell interviewed Dr Carlos Cheung — National’s young science graduate and property entrepreneur who looks to have defeated Labour’s Michael Wood in Auckland’s working-class suburb of Mt Roskill — he made no mention of Cheung’s linguistic prowess. Yet, under “languages”, Cheung’s LinkedIn profile states: “Cantonese, Chinese, English”. Why is this linguistic virtuosity not praised as remarkable when those able to speak and understand even a little te reo — or who are in the process of learning it — are so often not only lionised but sanctified by the media? And why are those who are not interested in learning te reo or critical of its random use in news reports and official information (no matter how many other languages they might speak themselves) so often demonised?

A principal reason is that the normal incentives to learn another language are mostly not in play with te reo Maori and it has to be fetishised to obscure that fact. Languages are primarily tools for efficient communication and the main reason most people will learn a new one is for its utility. It may be that another language is necessary for dealing with businesses in an export market; or it is needed to set up a new life or study in another country; or simply to make travel easier and more rewarding through contact with locals. More rarely, the desire stems from curiosity or a romantic interest piqued by a different culture and its history. Very few people, however, voluntarily commit themselves to the arduous task of learning another language from a sense of duty to rescue it from oblivion or from a sense of patriotism in the hope of helping form a distinctive national identity. Some will, of course, but the vast majority won’t.

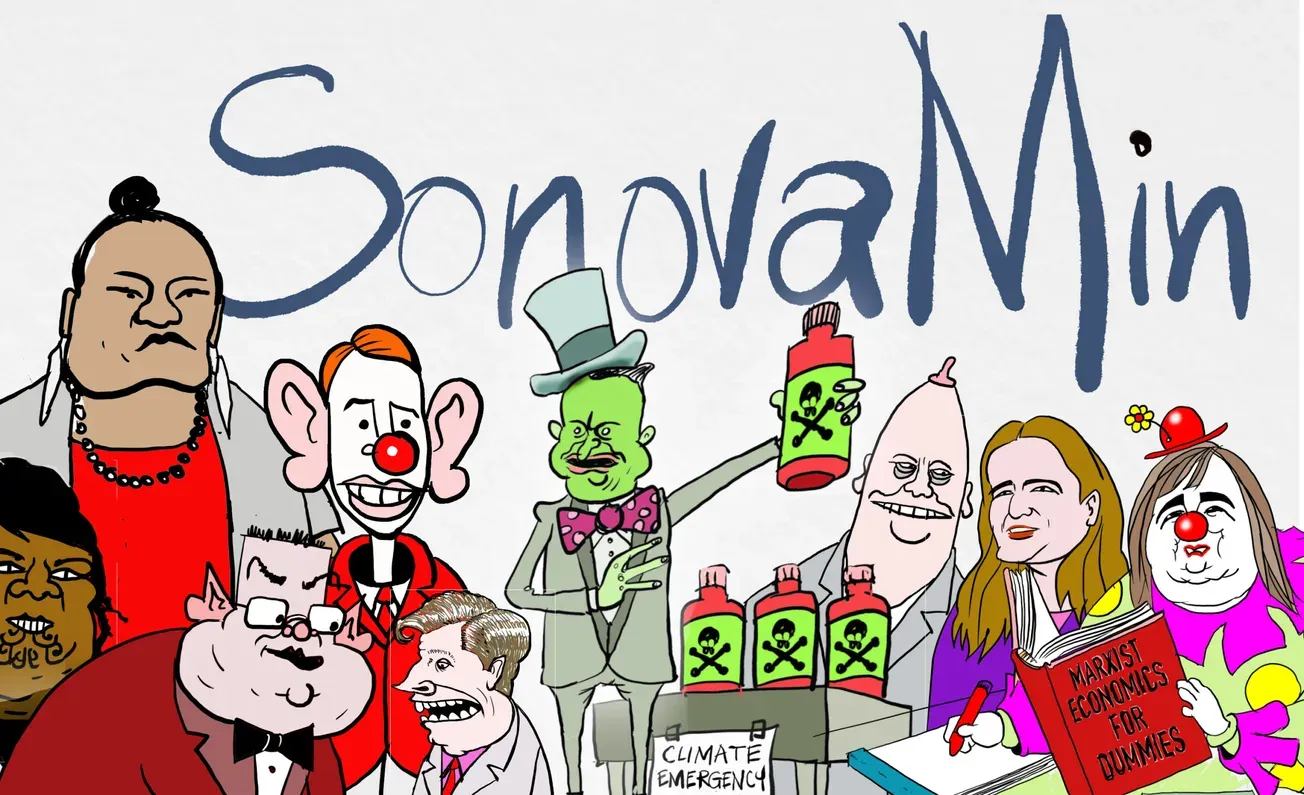

The government, media, schools and universities are doing their very best to create an artificial demand for te reo but unless the demand is organic, a language on “life-support” (as Professor Moon describes te reo) will always struggle to truly prosper. Consequently, language revivalists, and the media which backs them, cast learning te reo as a sacred “journey” that only deplorables and racists would reject taking part in. Thus, society is divided into the virtuous and the barbarians (a word, incidentally, that comes to us via Ancient Greece as a kind of onomatopoeia. It imitates the babbling sounds — “Ba-ba-ba” — that the Greeks heard when foreigners spoke in their own languages).

Last week in the NZ Herald, political commentator Matthew Hooton didn’t so much demonise as patronise those he sees as hostile to the proliferation of te reo in unexpected places:

“A minority of Pakeha, usually conservative and elderly, struggle with the speed with which te reo Maori is being adopted by the media and government agencies. They object to weather presenters saying ‘Otepoti’, rather than ‘Dunedin’ and government departments being called ‘Waka Kotahi – NZ Transport Agency’ rather than ‘NZ Transport Agency – Waka Kotahi’. A cuppa will help.”

However, when a poll conducted for The Post in mid-September asked whether “Government departments should be known by their English name, not their Maori name”, 49 per cent agreed, with only 26 per cent opposed. (25 per cent were unsure.) If those numbers are representative, it’s clear that objections are not confined to a minority of grumpy, older Pakeha as many journalists like to pretend. As one reader commented:

“[Hooton’s claim] is not correct. I have had discussions with immigrants from India and East Asia who are by no means old and who constitute a population that now makes up a considerable number of our overall population. They also object. No one asked them if New Zealand should be called Aotearoa, and don’t ask them what Te Whatu Ora means or how to pronounce it, because they don’t know. As far as they are concerned, they immigrated to an English-speaking country, not a Maori-speaking one.”

A senior lecturer in Classics, Dr James Kierstead — a graduate of Oxford, Stanford and the University of London — noted in an essay published in April that even a “language nerd” like him had found the use of Maori terms inserted into English text “confusing” when he arrived to teach at Victoria University. “Committees had names like Te Maruako Aronui. The university’s ‘Strategic Plan’ trumpeted values like whanaungatanga and kaitiakitanga (engagement and equity, if you’re interested). Higher-ups had alternative titles like Tumu Whakarae (Vice-Chancellor) and Iho Turoa (Assistant Vice-Chancellor, Sustainability).” He added:

“Recent immigrants understandably seemed to find them particularly bewildering. A Mexican friend in a new job told me she’d received an email ending with ‘Nga mihi’ and had insouciantly replied ‘Dear Nga…’”

How much is being achieved by scattergun attempts to revitalise te reo is uncertain. Such programmes have been underway for decades in New Zealand, but the numbers of those capable of speaking more te reo than a few words and phrases remain a tiny proportion of the population. And that appears to be true of Maori themselves. Te Manahau Morrison, an associate professor of te reo at Massey University — better known as Scotty Morrison, the presenter of TVNZ’s Te Karere — said last year that only 2.6 to 2.7 per cent of Maori speakers use the language on a daily basis at home. The key to a successful language revitalisation programme, he told The Listener, is getting it to be spoken in the home — and particularly in Maori homes.

Many critics believe that the responsibility of preserving te reo lies primarily with Maori. And if Maori don’t speak the language at home and pass it on to their children, the government adding words in te reo to road signs and Beehive press releases — and the media slipping it into news broadcasts — will never enable it to flourish as a living language. Pakeha in wealthy city suburbs enrolling in night classes won’t prevent its decline either. In fact, by soaking up the limited pool of te reo teachers, they are likely hampering tuition going to where it would be most needed to invigorate the language — Maori students who will speak it at home.