Table of Contents

There have been some astonishing fossil finds in recent years: everything from a nearly perfectly 3D ankylosaur (complete with remnant skin pigmentation) to a gigantic Queensland sauropod with remnants of its last meal in its innards and even a remarkably preserved dino cloaca. But a new discovery in Yunnan, China, while seemingly humble, is perhaps one of the most remarkable.

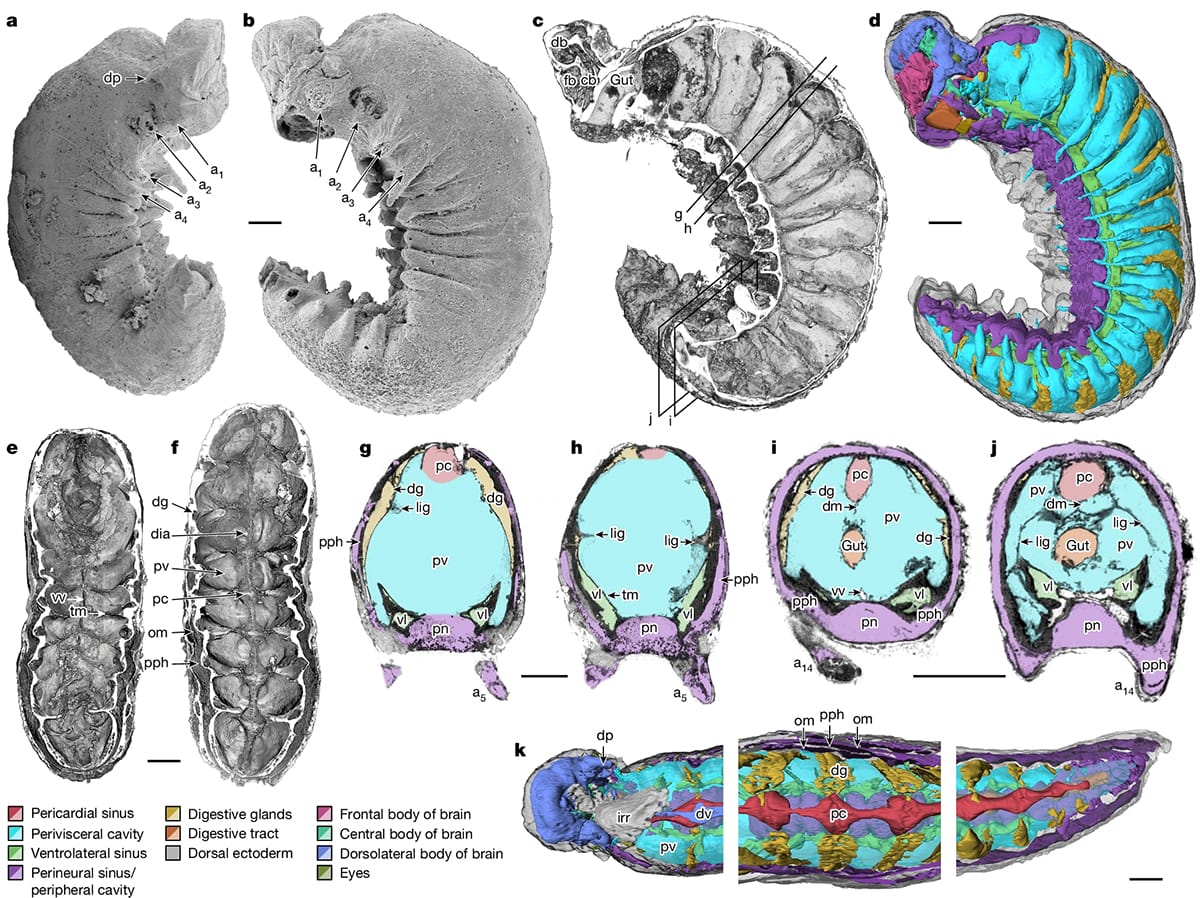

A tiny – less than one millimetre – fossil dubbed Youti yuanshi is the preserved larva of an ancient arthropod from one of the most extraordinary periods in the history of life on Earth. Dispute its miniscule size, the fossil is almost perfectly preserved in three dimensions and includes stunning details of its internal organs: the ‘brains and guts’.

Youti yuanshi lived some 520 million years ago, in the Cambrian period. Dubbed the ‘Cambrian Explosion’, this was an era when the first complex lifeforms, living in warm, shallow seas, embarked on a stunning age of experimentation.

Life in the seas was trying out every possible body plan, searching for combinations that worked.

Some of the results were truly bizarre, including the aptly-named Hallucigenia. Many quickly fell out of the evolutionary race, leaving behind no descendants today.

One line of creatures, the euarthropods, hit on a winner: segmented bodies, paired jointed limbs, and a knack for tweaking those limbs into claws, feelers, and walking legs. That design still powers today’s insects, spiders, and crabs.

The biggest problem for palaeontologists studying these astonishing creatures is that they had very few of the hard parts that are most likely to be fossilised. Thankfully a number of sites, in Australia, Canada, Greenland and China, preserved extensive galleries of these prehistoric bizarrities. Most, though, aren’t much more than outlines pressed into mud long since turned into rock and squeezed and flattened by aeons of geological activity.

Until Youti yuanshi. Y. yuanshi was a larval arthropod, the group that today includes modern insects, spiders and crabs. It is believed to be the infant form of the group of arthropods that included such Cambrian oddities as Anomalocaris, Opabinia, Pambdelurion and Kerygmachela.

What sets this fossil apart is its exceptional preservation of internal organs, offering a close-up view of life forms from a time unimaginable to us.

Using the cutting-edge synchrotron X-ray tomography at Diamond Light Source, the UK’s national synchrotron science facility, the research team was able to generate 3D images of this miniature marvel.

They unveiled brain regions, digestive glands, a rudimentary circulatory system and even traces of nerves supplying the larva’s simple legs and eyes […]

“When I used to daydream about the one fossil I’d most like to discover, I’d always be thinking of an arthropod larva, because developmental data are just so central to understanding their evolution. But larvae are so tiny and fragile, the chances of finding one fossilized are practically zero – or so I thought!” [lead researcher Dr Martin Smith from Durham University] enthused.

“I already knew that this simple worm-like fossil was something special, but when I saw the amazing structures preserved under its skin, my jaw just dropped – how could these intricate features have avoided decay and still be here to see half a billion years later?”

One revelation from Y. yuanshi is that even at such an early stage of complex life, these arthropods had an unexpectedly advanced anatomy.

This ancient larva holds the key to solving a myriad of questions on the evolution of multi-limbed creatures.

For instance, the fossil reveals an ancestral ‘protocerebrum’ brain region that was pivotal in our journey towards complex, segment-headed creatures.

The observations from this fossil help trace the path that led modern arthropods to gain their remarkable anatomical complexity and diversity.

Moreover, these findings fill a crucial gap in our understanding of how the arthropod body plan originated during the Cambrian Explosion of life.

Not only does Y. Yuanshi open up new insights into the evolution of much of the anatomical underpinnings of life on Earth today, but the techniques used in the groundbreaking study, such as synchrotron X-ray tomography, can be used on other fossils. The story of the origins and evolution of life is far from finished and, clearly, page-turning new chapters await.