Table of Contents

JR Bruning

JR Bruning is a sociologist (BBus Agribusiness; MA Sociology(Res)) based in the Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. Bruning is a trustee of Physicians and Scientists for Global Responsibility (PSGRNZ). Her primary research focus is on the relationship between governance, policy, and the production of scientific and technical knowledge for public good.

Food Standards Authority Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) have held two consultations to gauge public opinion on gene-edited ‘new breeding techniques (NBT) organisms', but have refrained from disclosing the balance of opinion in two past consultations.

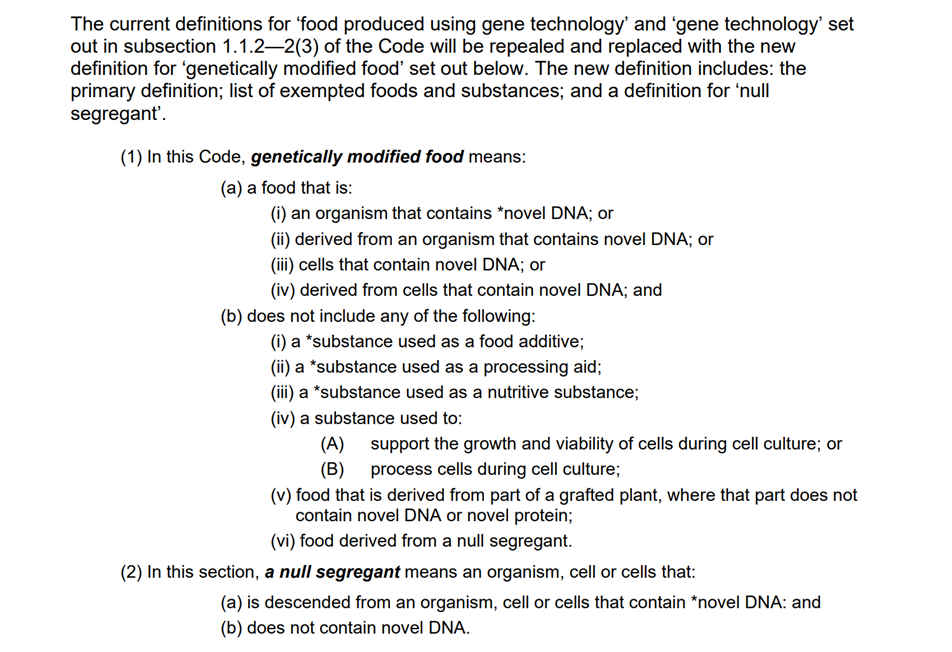

FSANZ are now holding another one which it states involves a ‘paradigm shift’ in how genetically modified organisms (GMOs) will be regulated. The paradigm shift involves GMO regulation shifting from being process-based, the organism was made using GMO techniques, to outcomes-based where a functional outcome is that the new organism will have novel DNA or a novel protein in it.

The P1055 consultation ends this Tuesday, 10 September. FSANZ consultation concerns a proposal to lock a new definition for gene-edited foods, also known as new breeding techniques (NBTs) in the Food Code. Gene editing technologies are new genetic modification techniques.

I suspect that once again, hundreds of people will send in responses, but FSANZ will, once again, fail to disclose the balance of opinion and fail to seriously consider information on GMOs and risk supplied by subject matter experts on risk.

It looks to me like FSANZ have jettisoned important democratic conventions in their long-term processes. FSANZs actions suggest that they are not accountable, nor are they fair and impartial.

CONSULTATIONS WRITE OUT PUBLIC OPINION

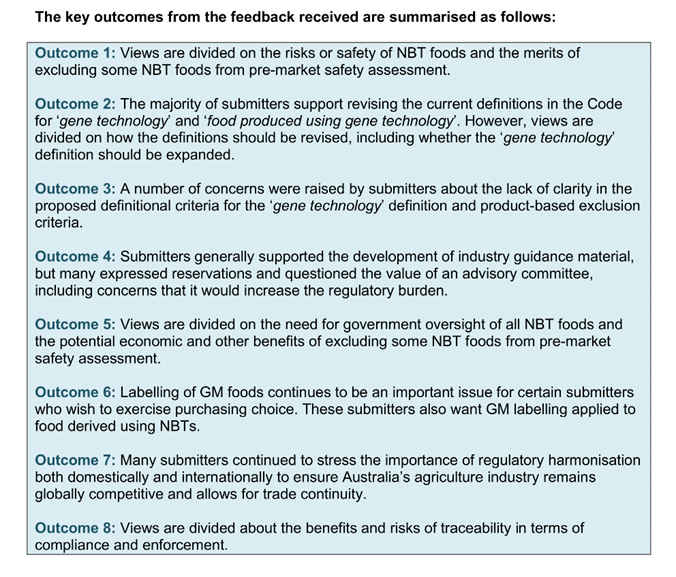

In 2018 and 2021, FSANZ did not disclose the weight of responses to their consultation questions. Responses came from scientific experts, policy experts, individuals and organisations that represented the interests of communities, health, environment, biotechnology, agricultural exporters and large multinational actors.

So, for some groups there were clear financial conflicts. Foods where small insertions and deletions have been made that altered a genome, would be outside the new regulation and wouldn’t have to be declared. These GMOs would evade pre-market assessment and avoid GMO labelling. The GMO developers and corporations who own the GMO patents would not only save money on risk assessment processes, but might get more money per tonne for their product. Consumers all over the world pay less for GMO food and more for non-GMO food. FSANZ’s own research corroborates with this understanding.

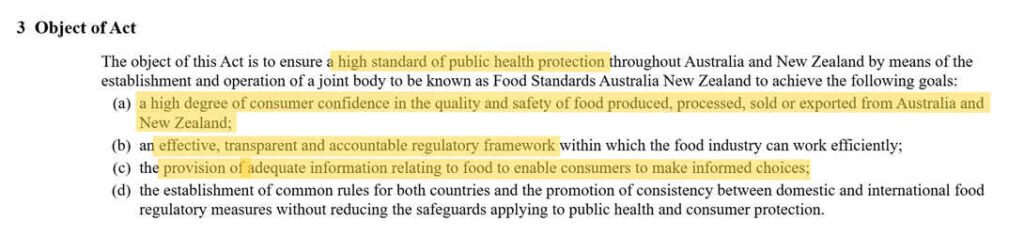

It seems that Australia and New Zealand’s food-safety agency is gaming the government process, but then developing regulations that effectively hide GMOs so that the public cannot choose. This is even more strange when FSANZ is legally obliged to ‘provide adequate information’ so people can make ‘informed choices’.

The current process-based definition includes food produced using gene technology if GMOs had changes to the genome. For example insertions and deletions of DNA would no longer be considered as GMOs.

Large numbers of groups and individuals responded to the consultations: 664 responses were made in 2018, and discussed in the Preliminary report: Review of food derived using new breeding techniques – consultation outcomes; while 1736 submissions were made in the 2021 consultation, which was summarised in the Safety assessment: full technical report. P1055 – Definitions for gene technology and new breeding techniques.

FSANZ generalised in its assessments in both 2018 and 2021. Their actions fail any transparency and impartiality test, in fact, and the implications of sidelining public input is disingenuous (when they claim to want to understand public opinion) and ethically troubling.

MANUFACTURING CONSENT FOR THE RECLASSIFICATION PUSH?

It seems that FSANZ picks and chooses when it will review responses.

It’s hypocrisy on steroids when FSANZ also goes to the trouble to pay for documentation that, to all appearances, supports a predetermined agenda.

In 2021 a FSANZ financed and contracted focus group surveys and a report. Focus groups on consumers’ responses to the use of New Breeding Techniques (NBTs) in food production was published by FSANZ.

Were hundreds involved? No, only 79. Of the 79 participants, 32.9 per cent considered that the information presented to them was ‘somewhat biased in favour of gene technology’. The charts in the published paper overwhelmingly suggested that the participants were in favour of the NBT scenarios pitched at them. But it is noteworthy that the participants thought that the Fact Sheet they were presented with should have had ‘more details on risk assessment procedures and approval processes, and whether and how ongoing monitoring will occur’ and more information on the ‘Long-term risks of use of this type of technology’.

DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION BE DAMNED?

What words can we use to articulate FSANZ’s approach? It looks to me like procedural norms of fairness and transparency have gone out the window. Process is critical. Because:

‘The durability of public facts, accepted by citizens as ‘self-evident’ truths, depends on the procedural values of fairness, transparency, criticism, and appeal.’

As I have discussed, judges also rely on administrative law conventions which ensure good process in the courts. But when conventions such as fairness and impartiality go out the window, when public opinion input from experts is sidelined, the information which then claims to underpin a proposed policy trajectory essentially becomes fundamentally untrustworthy.

Professor Philip Joseph notes:

Public servants, too, must exercise discipline and restraint. They operated under a code of conduct that is intended to preserve their neutrality and anonymity. They owe a duty of loyalty to their employer, the government of New Zealand, and are expected to uphold the public service ethic (knowledge, fairness, integrity). They must be ‘fair, impartial, responsible and trustworthy’, and their advice to ministers honest, impartial and comprehensive. A public servant’s duty is to the government in perpetuity, not the political party or parties in power at any time.

(Joseph, P. (2021). Joseph on Constitutional and Administrative Law, 5th Ed. Thomson Reuters, 10.5.4)

GENE EDITED FOOD ‘SUBSTANTIALLY EQUIVALENT’ TO CONVENTIONAL FOOD

FSANZ proposal to change the Food Code means that anything that doesn’t fit their new definition won’t be called a GMO and that all these other ‘things’ that don’t fit the definition can be found in nature anyway.

FSANZ are using ‘substantial equivalence’ rhetoric to bat away inconvenient issues.

FSANZ recent unpublished webinar shed light on the extent to which FSANZ staff have locked in the belief that any product of gene editing that doesn’t result in novel DNA or a novel protein is substantially equivalent to conventional food.

The perspective of the science experts on the webinar panel strongly suggested an institutional ‘norm’ or fact – that gene edited GMOs that do not produce DNA or a protein is substantially equivalent as safe, was firmly entrenched as the consensus position of FSANZ.

The implications of such a belief is that unless a GMO contains novel DNA or a novel protein, FSANZ will generally regard as safe both the hazard and the greater impact in human bodies and the environment. No risk assessment is required. No GMO labelling is required. This ‘not’ GMO is safe.

How did FSANZ arrive at this consensus position? They’ve drafted reports and released consultation documents, but then hold consultations where they rely on rhetorical brinkmanship.

WHAT IS THE PARADIGM SHIFT?

FSANZ currently assesses the risks of all products that have undergone processes of genetic modification (GM). This encompasses older genetic modification techniques and newer ones using gene editing tools like CRISPR. This is a process-based, case-by-case method. It recognises that different GM organisms (GMOs) will come with different risks. Some might be grown widely in the environment, some might be sprayed on food, others might be produced in stainless steel, and commonly or occasionally used in food.

Patents confer monopoly rights on NBTs, while it is much harder to patent conventional bred foods. The patent potential acts as an incentive to production.

This has fostered the revolution in gene editing, and the scale and pace of development and release of gene edited NBTs.

But this acceleration development is out of scope. Because the only risk FSANZ concerned itself with in past reviews (here and here) has been ‘do the small changes observed in NBTs also occur in conventional food’? The pace of development is utterly ignored through a process of failing to engage when subject-matter experts do ask FSANZ to consider such a risk scenario. The current 2024 consultation continues the pattern.

FSANZ knows that (p.39) process-based to outcomes-based is a massive paradigm shift. This second call for submissions opened a month ago, yet neither Australian nor New Zealand MSM have covered it.

As the proposal text shows, a ‘not a GMO’ will expand to include substances used as food additives, processing aids, nutritive substances. Even substances used to develop cell culture will be excluded from the GMO term.

The obligations that FSANZ has to the public can be found in s.3 of the Food Standards Australia New Zealand Act 1991. FSANZ are required to place food safety as a top priority, and to ensure adequate information, so that the public may make informed choices.

RISK ASSESSMENT SUBVERTED FOR ‘CLARITY’?

FSANZ appears trained on clarity, objectivity, compliance and consistency and the questions in the latest consultation reflect this staggeringly narrow scope.

But while hazard, the potential for something to cause harm, is one component of risk assessment, how a hazard interacts in the environment, the extent to which a hazard is present or not, involves reviewing and assessing how a hazard might cause or increase a set of risks.

This part of risk assessment, the scalar nature of the tech, is out of scope because the framing around risk has been limited to arriving at a definition that discounts so-called small changes including insertions and deletions.

The black and white ‘clear and objective’ definition is the functional outcome, the DNA or the protein.

But it’s not objective because FSANZ is ignoring a major element of risk assessment.

I’ve discussed the scalablity problem with Professor Jack Heinemann, specifically in relation to one of the NBT categories that FSANZ intends to exclude as a potential GMO.

There is evidence that gene edited organisms not producing novel DNA or novel protein, still come with a risk of harm, largely because of damage to the DNA during the editing process(e.g., here and here).

From what I can assess from earlier papers, FSANZ only consideration of off-target risk has been at the genome level.

It’s not just the organism, it’s the problem of being rolled out into the environment or into human bodies rapidly at scale far beyond the pace of new varieties of conventionally bred foods. It’s the question of off-target effects that might not only impact the health and resilience of humans but of other organisms. These risks can be modelled, but they are outside FSANZs focus right now.

FSANZ seems to be deflecting uncertainty.

I do recommend that all food industry exporters take a gander at FSANZ Cost Benefit analysis which has failed to consider both consumer preferences and the price premium of non-GMO food.

New Zealand media has not covered this issue, leaving farmers, growers, the general public and our food exporters in the dark about the implications of such a proposal, were it to pass into legislation.

FSANZ proposal glides over contradictions that are as yet unresolved, and from my perspective, appear contrary to public health and public values. But perhaps that is just my opinion.

This article was originally published by Daily Telegraph New Zealand.