Table of Contents

We tend to think of ancient humans as primitive, but they made some of the most crucial mental leaps in human history. Agriculture, for instance. Metallurgy. Pottery. And, of course, writing.

How did writing even emerge? A new study suggests a surprising – and surprisingly ancient – possibility.

Pottery and writing were contingent on agriculture. For nomads without pack animals or wheeled transport, pots are far too fragile and cumbrous to bother with. Sedentary agriculturalists, on the other hand, need secure vessels to store grain and other produce.

Agricultural societies engaging in systematic trade also need a way of keeping track of their goods. Memory can only go so far, and, when disputes arise, without written records it becomes one party’s word against the other’s.

Unsurprisingly, then, the earliest recognisable writing, in the form of pictographs, dates to around 6,000 years ago, in the cradle of civilisation, Mesopotamia.

The Mesopotamian city of Uruk [was] located in what is now Iraq. Uruk was a major trade hub, reaching as far as southwestern Iran to southeastern Turkey.

To track the flow of and payment for goods, tradespeople then used cylinders with designs engraved upon them. Think of them as an early version of a rubber stamp – but one that rolled across a wet clay tablet rather than pounded onto a paper surface.

Scholars then tried to find as many matches as they could between images on the cylinders and an early or proto version of cuneiform. The proto version lies in that fuzzy area between symbol and language.

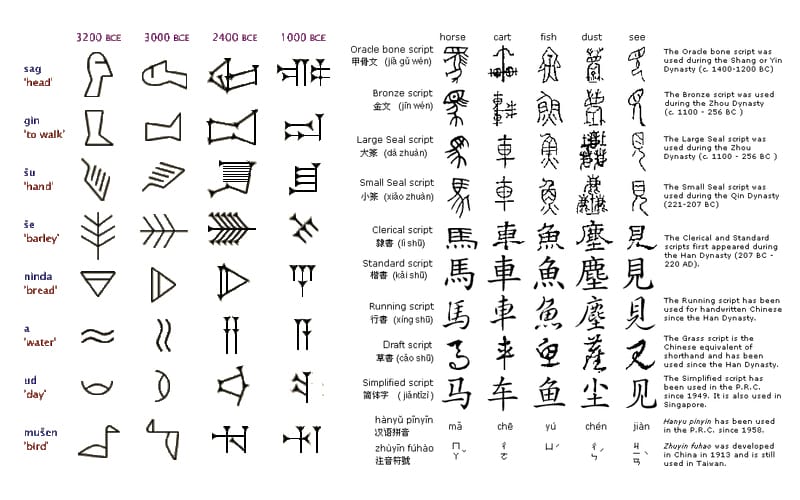

The evolution of pictograms, simple pictures representing concepts rather than actual words, into symbols can be seen below. It didn’t just take place in Mesopotamia: a similar process took place in China and Mesoamerica.

Writing was independently invented at least four times in human history: in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and Mesoamerica. The scripts of these civilizations are considered pristine, or developed from scratch by societies with no exposure to other literate cultures. All other writing systems are thought to be modeled after these four, or at least after the idea of them.

Unlike China, Mesopotamia and Egypt went further: abstracting symbols for whole words into phonemes (basic phonetic sounds) and then into full-blown alphabets.

That was far in the future. Still, once started as pictograms, the evolution of writing gathered pace.

The origins of the first picture-language symbols could be even more ancient than we’ve previously suspected.

A new paper published in the Cambridge Archaeology Journal pushes this date back by about 15,000 years.

According to the paper, Ice Age individuals scored and painted strange symbols, including dots, slashes and asterisks, on rock surfaces inside and outside of caves and across portable items such as sticks and stones, to record the seasonal activities of their favorite animals. If these findings stand up under scrutiny, it may mean that our ancient ancestors were much more advanced than previously appreciated.

As well as their magnificent cave paintings, Ice Age people left behind many artefacts adorned with abstract patterns, including the cave paintings themselves. It was long assumed that these were merely decorative.

Working with the supposedly “uncontroversial” assumption that these sequences maintained some sort of notational or numerical meaning to their makers, a team of researchers recently assessed a series of 862 animal representations from the Upper Paleolithic to translate the three widest spread symbols: the dot, the slash and the y-shaped sign.

Ultimately, the team surmised that the number and the placement of these symbols related information about the mating and birthing of their associated animals, which was of the utmost importance to individuals of the time.

“It is no surprise that thinking about animals is central to hunter-gatherers’ being in the world,” the researchers state in their study. “It follows that knowledge of the timing of migrations, mating and birthing would be a central concern.”

The researchers have catalogued an astonishing array of 862 separate animal-and-sequence associations, with 606 featuring a series of dots and slashes and 256 featuring a series of dots and slashes and well as y-shaped strokes. Surprisingly, like the cuneiform and Chinese writing that lay tens of thousands of years in the future, these symbols use a remarkably few set of basic marks: just 13.

Using statistical analysis to scrutinize these animal-and-sequence associations further, comparing patterns of birthing, mating and migration to patterns of dots, slashes and strokes, the team found that the simple dots and slashes symbolized the number of synodic months after the start of the spring (out of the total of 13) that the associated animals started to mate. Alternatively, they found that the placement of the Y-shaped strokes symbolized the beginning of the species’ birthing season.

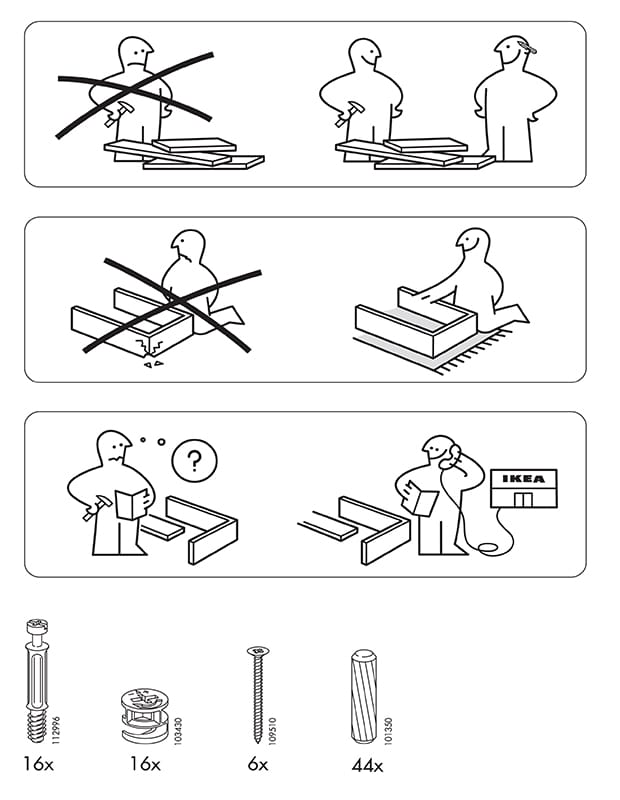

These are a long way from being ‘writing’, of course. Think of them as more like the pictorial instructions accompanying an IKEA furniture kit. While they may not convey the nuance of written language, these simple symbols can pack an incredible amount basic information.