Table of Contents

As current conflicts in Ukraine and Iran are showing, the battlefields of the 21st century are increasingly unlikely to be on the ground. The air is more important than ever before, but two new combat spaces are emerging: space and cyberspace. While space-based warfare is still in its infancy, cyber warfare has already emerged as a critical battlefield. Hackers wreck combatants’ communications and financial capabilities, while regimes try to deny internet access to their subjects – and disruptors like Elon Musk use technologies such as Starlink to give it back to them.

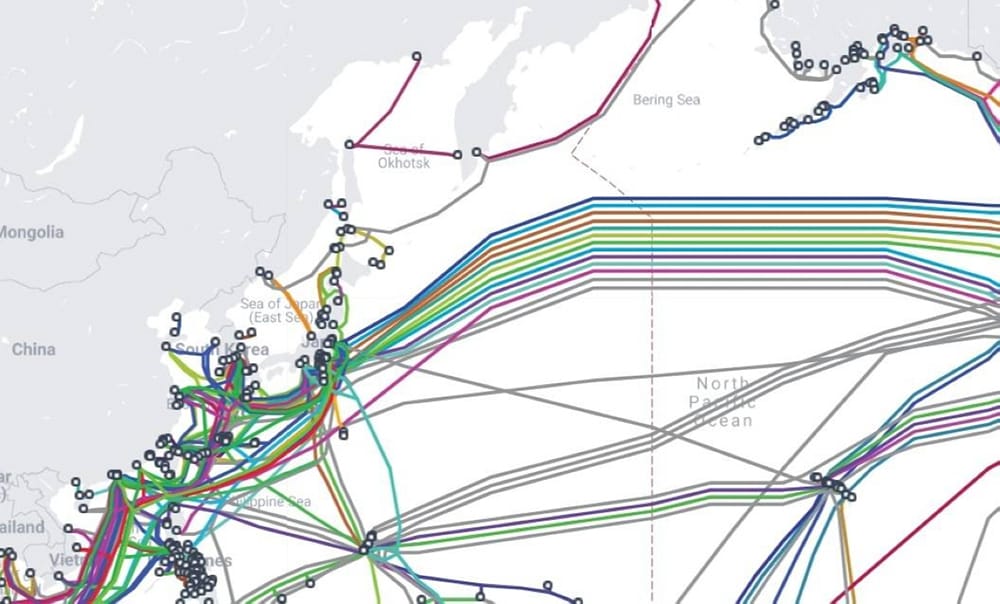

The new battlefield of cyberspace is also intersecting with one of the ancient combat spaces after the earth itself: the sea.

Many nations, Australia and New Zealand especially, rely heavily on undersea cables for the vast bulk of their internet traffic. So does the island nation of Japan. As such, Japan is acutely aware of the implications of recent alleged sabotage of undersea cables around the world – and especially near Taiwan (gosh, I wonder who could it be?).

The government is increasingly aware of the risk. Tucked into this year’s economic and fiscal policy guidelines, referred to as honebuto no hōshin, which set the tone for budget planning for the next fiscal year, is official recognition of submarine cables as strategic infrastructure vital to Japan’s economic security.

What exactly are undersea cables, and how real is the threat of disruption – especially for a country such as Japan, which faces frequent natural disasters and growing geopolitical tension?

As Tasmanians learned the hard way, cutting an undersea cable can almost completely disrupt critical communications. Twice now, damage to the Basslink undersea cable has caused havoc in the island state. In 2016, damage to the cable helped precipitate an energy crisis. In 2022, cutting both Basslink and its backup cable within hours of each other plunged the state into telecommunications darkness. Businesses couldn’t conduct transactions, banks and ATMs shut down, limiting cash as well, and all inbound and outbound flights stopped. Even the emergency 000 telephone network was down.

All because of cutting cables not much thicker than a garden hose – but packed with dozens to thousands of optical fibre.

These fiber-optic lines handle 99 per cent of Japan’s international communications, powering everything from email and banking to video calls and cloud computing. They’re the invisible infrastructure that keeps the global internet humming […]

Japan – a hub of undersea cables connecting the United States and Asia – is directly connected to 20 to 30 international cables, according to the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry.

Unlike Tasmania, Japan therefore has many layers of multiple redundancy. Cutting just one or two cables by accident won’t cut Japan’s communications, but what if a malicious actor simultaneously attacked them all?

The Baltic Sea incident in late 2024 drew international attention when a ship dragged its anchors along the seafloor for kilometers, severing cables along the way. The event led NATO to deploy military ships to patrol the area.

Taiwan has also faced repeated undersea cable cuts involving China in recent years. But Jun Murai, a professor emeritus at Keio University and expert in undersea cables, noted that these incidents are likely caused by Chinese fishing vessels rather than military activity.

When it comes to China, though, where every ‘private’ company is answerable to the Chinese Communist Party, is there a functional difference?

Fortunately for Japan, it is home to one of three dominant companies in the world in submarine cable: France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN), in which the French government has a majority stake, US-based SubCom and Japan’s NEC. But China’s Huawei, which some Western countries have banned from participating in their 5G networks, is trying to increase its market share.

Murai said that while political concerns have led some to hesitate over government-owned manufacturers such as ASN, NEC’s status as a private Japanese company has helped grow its business, particularly as buyers seek stable, politically neutral sources for their infrastructure.

“So now ... NEC has become stronger,” he said.

Another challenge is Japan’s limited number of cable-laying ships. KDDI and NTT both own such vessels, but NEC is the only cable manufacturer that does not own any, although it started renting one in 2022.

The Japanese government has budgeted ¥10 billion ($69.6 million) to shoring up its submarine cable infrastructure. Measures include diversification of submarine cable routes and landing stations in Japan.

“Submarine cables used to be considered just communications infrastructure,” Murai said.

“But today, they’re the foundation of the entire economy. Everything from artificial intelligence to health care, energy, and education depends on stable, high-capacity digital connections.”

Meanwhile, while Tasmania with its 575,000 people relies on just two submarine cables, New Zealand’s five million are critically dependent on… four.