Table of Contents

Burn, Hollywood, Burn

A regular review by John Black

There should be an entire circle of Hell dedicated to people who opine on movies without seeing them first. More than any blockbuster movie in recent memory, Joker has been the victim of such predestinarian soothsaying. Based on nothing but the trailer, Woke warriors took to twitter hyperventilating that Joker was excuse-making for white supremacist and INCEL mass shooters.

In response ‘the Alt Right’ (who I’m convinced don’t really exist as a political grouping beyond being young male internet trolls) organised a campaign to boost its IMDb score – getting it a 9.7 (the highest of any comic book movie), a month before it was released. Meanwhile, critics have bloviated on the (unproven) link between violence on the screen and in real life, often citing John Hinckley Jr. who tried to take out Ronald Reagan after seeing Taxi Driver, a movie that depicted a political assassination (and that Joker clearly references). Interestingly, the printed word seems to escape similar accusations when the Bible and in particular the Koran have inspired murderers aplenty. Mark Chapman gunned down Lennon after reading Catcher in the Rye. But then again Son of Sam reckoned his dog told him to do it, so who the hell knows. These people are crazy.

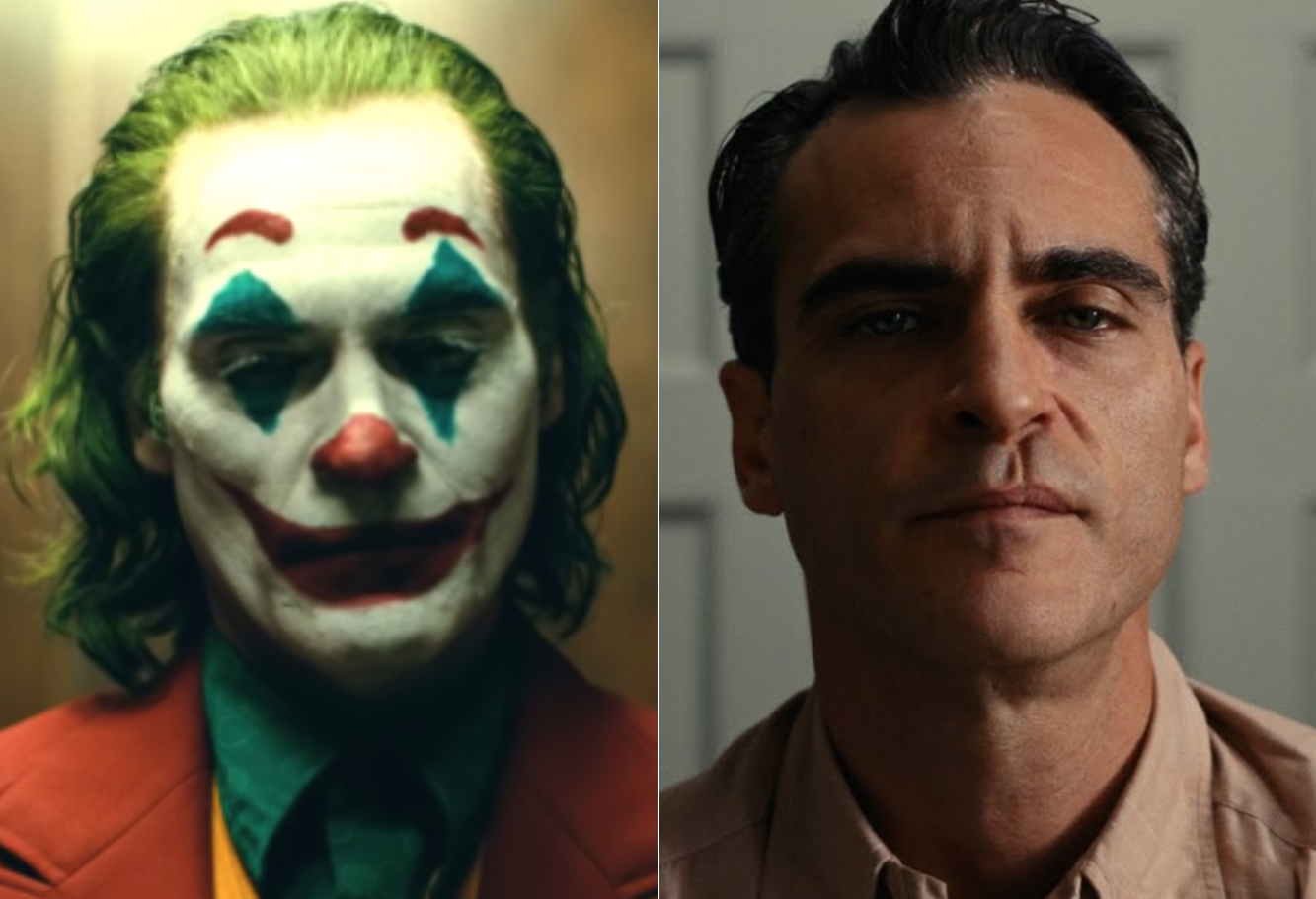

It’s perhaps fitting that such insane posturing should surround a movie about madness. Having now seen the movie I believe Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker is the most convincing portrayal of a descent into insanity in cinema since De Niro’s Travis Bickle. Joker (Arthur Fleck) begins as an oddball loser, getting pushed into delusion by vile circumstance before becoming utterly seduced by the power of going bat shit crazy. Phoenix manages to convey this journey almost entirely physically. Starting as a coiled spring of tense resentment he flowers in the latter scenes into an expansive gesticulating confidence, doing a mad Gene Kelly routine down the streets of Gotham. But in one of the key scenes, there is little movement at all. Arthur sits alone in a nightclub watching a comedian (recalling Scorsese’s King of Comedy, he aspires to a stand-up comedy career, hence ‘Joker’), his loud braying laugh coming a few beats behind everyone else’s. He doesn’t know what’s funny, his eyes darting to the other patrons trying to anticipate the next laugh. A man out of sync with the world, a would-be comedian without a sense of humour. Seldom has a movie character been more pitiable. It’s a great acting performance and Phoenix should get an Oscar unless a movie about a gay disabled black guy overcoming prejudice comes out before the end of the year.

This is a super-villain movie, rather than a superhero movie. Phoenix is in almost every scene, and Batman is only present as the child Bruce Wayne. Some have found the tone grim for a comic-book movie and compared to the whizz bang Marvel movies, it is. But I wonder how many of those critics have actually picked up a comic book in the last twenty years. Adult themes and dark content are common. It ain’t all men in primary coloured capes and budgie smugglers saving the World any more (thank God). The magnificent score by Hildur Gudnadottir (heavy on the cello with a minimal electronic assist) and the seedy 70s New York feel of the set design for Gotham add to the heavy atmosphere of dread in the film. The tempo of the plot slows a little in the middle as Arthur’s beat downs become a tad repetitive, but the final twenty minutes deliver, with his appearance on an inane talk show hosted by cheesy fraud, Murray Franklin (Bob De Niro) exploding into violence as Arthur truly transforms into Joker.

So what of the controversy? Is there anything dangerous about this movie?

Joker sets out, through means of a character study, the case for nihilism. Overwhelmed by injustice – poverty, loneliness, social animosity and psychological illness – Arthur concludes that life itself is nothing but an absurd cosmic joke. Arriving at the existentialist full stop, he hopes, as he writes in his journal, that ‘death will make more sense than my life’. If life has no value, death becomes the only value – the logic of the serial killer.

In the final moments of the film, anarchic violence claims Bruce Wayne’s parents. Joker, born from injustice, in abandoning the moral struggle, has merely added to the injustice in the world. But the audience knows too, that Bruce Wayne’s Batman is also born from this injustice and, taking a superior path, will dedicate his life to fighting it.

Perhaps those most discomforted by Joker find his despairing immorality just a little bit too familiar.