Table of Contents

H. G. Wells once said that anyone who pined for “the good old days” would change their mind as soon as they got a toothache. If they had read some of the “medical” treatments available in the Middle Ages, they might not have been so keen on the old days in the first place.

Cambridge University Library is currently undertaking a two-year project, dubbed “Curious Cures”, which will digitise and catalogue over 180 medical manuscripts. The collection contains about 8,000 medical recipes, in manuscripts, including illuminated manuscripts, academic treatises and simple pocket-books. Most are from the 14th and 15th centuries, although the oldest is a thousand years old.

The recipes typically comprise a short series of simple instructions, just like in a modern-day prescription or cookery book.

In these texts, we find many common or garden ingredients that we would know today – but also some more curious or questionable components, in particular those deriving from animals.

One treatment for gout involves stuffing a puppy with snails and sage and roasting him over a fire: the rendered fat was then used to make a salve. Another proposes salting an owl and baking it until it can be ground into a powder, mixing it with boar’s grease to make a salve, and likewise rubbing it onto the sufferer’s body.

To treat cataracts – described as a ‘web in the eye’ – one recipe recommends taking the gall bladder of a hare and some honey, mixing them together and then applying it to the eye with a feather over the course of three nights.

Supervisor of the project, Dr James Freeman, says that, “These recipes are a reminder of the pain and precarity of medieval life: before antibiotics, before antiseptics and before analgesics as we would know them all today.”

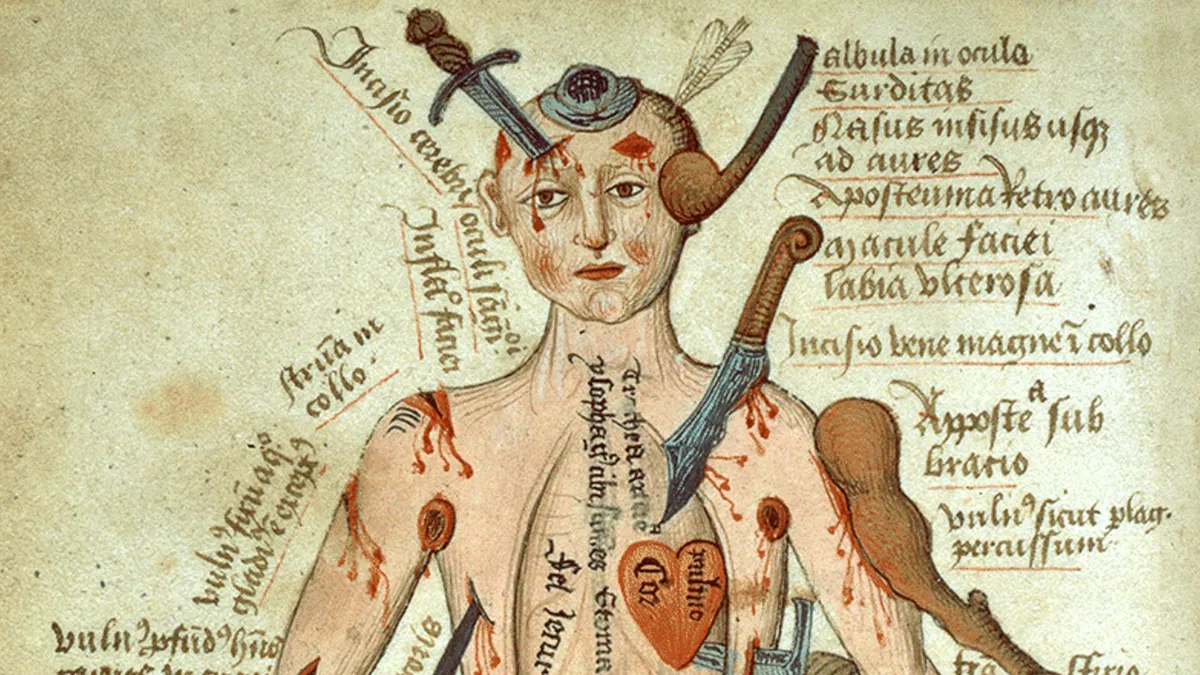

As well as day-to-day complaints, these recipe books reveal some of the troubling and grisly ailments that afflicted medieval people: flesh that grows in a man’s eye, virulent ulcers, fistulas and cancers. Some highlight the violence of medieval life: how to determine whether a skull has been fractured after a blow from a weapon, how to staunch bleeding or set broken bones.

Others refer to “sores… of sword, knife and of arrow, be the wound wide or narrow”. Others refer to less violent but no less horrible-sounding afflictions as “worms that eat the eyelids” and “him that spitteth blood”.

It’s notable, too, that many of the recipes include, not just animal-based “treatments”, but “natural ingredients” such as herbs.

There are herbs that you would find in modern-day gardens and on supermarket shelves – sage, rosemary, thyme, bay, mint – as well as common perennial plants: walwort, henbane, betony, and comfrey.

Medieval physicians also had access to and used a variety of spices in their formulations, such as cumin, pepper, and ginger, and often mixed ingredients with ale, white wine, vinegar or milk.

Cambridge University Libraries

Looking down from our lofty perch of 21st century medicine, it’s worth pondering that people in a few centuries hence may well regard our modern medicine with similar horror as Dr McCoy in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. “Dialysis? My god, what is this, the Dark Ages? We’re dealing with medievalism here! …Chemotherapy! …Fundoscopic examinations!”

Even in the past 100 years, medicine has progressed such that the collection of antique instruments on display in my local hospital’s corridor looks like a museum of mediaeval torture devices.

At the same time, some people seem bent on taking medicine back to, not just the Middle Ages, but the Stone Ages.