Table of Contents

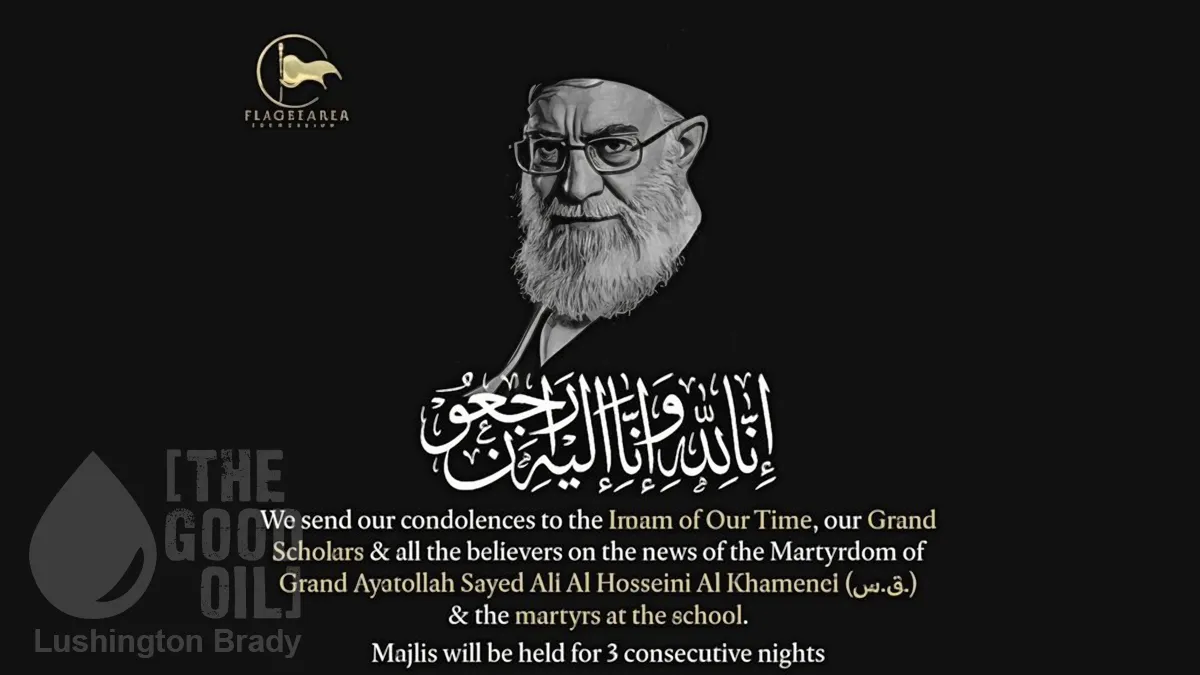

It should surprise no one that Muslims attacked Jewish Australians this week. As former PM Tony Abbott notes, there has been a “notable presence of recent migrants from the Middle East in the pro-Hamas demonstrations that erupted in Sydney and Melbourne”. Not so much notable as overwhelming. Of course, anti-Semitism is endemic in the Islamic world, because, not least, it’s openly promoted by Islamic scripture. Indeed, the daily prayer of Muslims calls down Allah’s wrath on Jews.

Unfortunately, Christianity, too, has a long, sordid past history of anti-Semitism, often promoted by a tendentious interpretations of scripture. Even in the wake of the Bondi massacre, some ‘Christians’ are still muttering ancient hatreds about so-called ‘Christ-killers’.

But is this actually true?

What many Christians seem to forget – indeed, some, bizarrely, actively deny it – is that Jesus – or more correctly, Yeshua ben Yosef – was himself a Jew. In the context of his own time, he was a Jewish reform preacher. It was at least 30 years after his death before his followers began to be called – by others – ‘Christians’.

While many people now regard Jesus as the founder of Christianity, it is important to note that he did not intend to establish a new religion, at least according to the earliest sources, and he never used the term “Christian.” He was born and lived as a Jew, and his earliest followers were Jews as well. Christianity emerged as a separate religion only in the centuries after Jesus’ death.

The primary – indeed, overwhelming – sources for what we know about Jesus were written by Jews: at least three of the four Gospels. The foundational Christian corpus of texts were written by Paul, a Jew, as well. Indeed, all but two (or perhaps four) of the books of the New Testament were written by Jews. The first-century Jewish historian Josephus mentions Jesus, although it is suspected that some of his work was later embellished by Christian scribes.

A more pertinent question might be: did Jesus reject Judaism?

Some have interpreted certain verses in the gospels as rejections of Jewish belief and practice. In the Gospel of Mark, for example, Jesus is said to have declared forbidden foods “clean” – a verse commonly understood as a rejection of kosher dietary laws – but this is Mark’s extrapolation and not necessarily Jesus’ intention. Jesus and his earliest Jewish followers continued to follow Jewish law.

The New Testament also include numerous verses testifying to Jesus as equal to God and as divine – a belief hard to reconcile with Judaism’s insistence on God’s oneness. However, some Jews at the time found the idea that the divine could take on human form compatible with their tradition. Others might have regarded Jesus as an angel, such as the “Angel of the Lord” who appears in Genesis 16, Genesis 22, Exodus 3 (in the burning bush) and elsewhere.

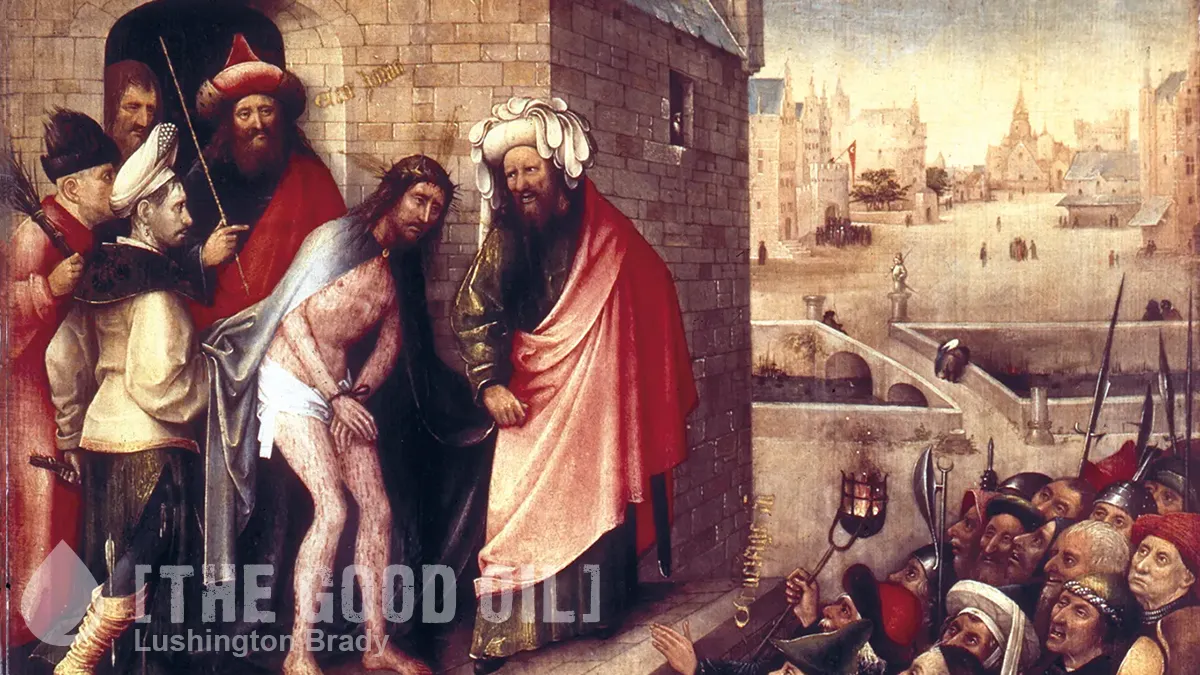

But the big question, the one which has really strained Jewish-Christian relations for millennia is the accusation that ‘the Jews killed Jesus’. Is it true, though?

No. Jesus was executed by the Romans. Crucifixion was a Roman form of execution, not a Jewish one.

But don’t the gospels show that the Jews demanded Jesus’ death?

According to the Gospel of Matthew, after Pilate washes his hands and declares himself innocent of Jesus’ death, “all the people” (i.e., all the Jews in Jerusalem) respond, “His blood be on us and on our children” (Matthew 27:25).

This “blood cry” and other verses were used to justify centuries of Christian prejudice against Jews. In 1965, the Vatican promulgated a document called “Nostra Aetate” (Latin for “In Our Time”) which stated that Jews in general should not be held responsible for the death of Jesus. This text paved the way for a historic rapprochement between Jews and Catholics. Several Protestant denominations across the globe subsequently adopted similar statements.

It is one of the most grotesque ironies of history, in the end, that a people’s own religious writings have been weaponised so violently against them.

It must be remembered, first of all, that Matthew was written decades after the fact, and likely at least 10 years after the earliest surviving gospel, Mark, which doesn’t mention such an incident at all.

This is critical: Matthew is not an eye-witness account, but a theological reflection written decades later. In this sense, Matthew is trying to symbolically link Jesus to earlier prophetic traditions, particularly the rhetoric of responsibility: the idea that disasters which befell communities were a consequence of their sins. Christians similarly long viewed sin as an existential threat to the entire community.

Matthew is not blaming the Jewish people as a whole, but the Jews of the time, and of Jerusalem alone.

If it wasn’t at the Jews’ insistence, why was Jesus killed?

Some have suggested that Jesus was a political rebel who sought the restoration of Jewish sovereignty and was executed by the Romans for sedition – an argument put forth in two recent works: Reza Aslan’s Zealot and Shmuley Boteach’s Kosher Jesus. However, this thesis is not widely accepted by New Testament scholars. Had Rome regarded Jesus as the leader of a band of revolutionaries, it would have rounded up his followers as well. Nor is there any evidence in the New Testament to suggest that Jesus and his followers were zealots interested in an armed rebellion against Rome. More likely is the hypothesis that Romans viewed Jesus as a threat to the peace and killed him because he was gaining adherents who saw him as a messianic figure.

The Romans took such things bloodily seriously, after all. While the Romans could be (by the standards of the day) relatively benign overlords, the Pax Romana was heavily contingent on their subjects doing as the Romans did. That included obediently paying homage to the official cults recognised by the Roman state. The Jews’ refusal to bend their necks to such idolatry as the cults of the god-emperors spurred repeated Roman repression.

Pilate himself had clumsily provoked violent riots by bringing Roman military standards bearing cultic effigies of the emperor into Jerusalem. After five days of riots, Pilate backed down. Only to spur more riots by appropriating Temple funds for an aqueduct project – this time, rather than back down, Pilate seeded disguised soldiers, who at his signal clubbed and killed many Jews.

So the idea that a Jewish preacher was gaining followers and causing trouble with the officially tolerated religious practices was not the sort of thing Pilate was going to let get out of hand again.

In the end, then, it really was the Romans who killed Christ – just as they killed so many of the early Christians.

And Christians went on to kill so many Jews. Would we want their blood to be “on us and our children”?