Table of Contents

Sailing east from there, Tasman sights the west coast of yet another unknown land on 13 December 1642. It’s the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand, somewhere in the vicinity of Hokitika and Perpendicular Point (“a large, high-flying land” 171oE, 42oS).

Tasman sails north along the west coast of the South Island and around the top, puts into Golden Bay hoping to land, and here becomes the first “white turnips” to see the Maori (“large brown men with their hair on the top of their head with a feather in it, wearing mats and paddling strange double canoes”, 18 December 1642).

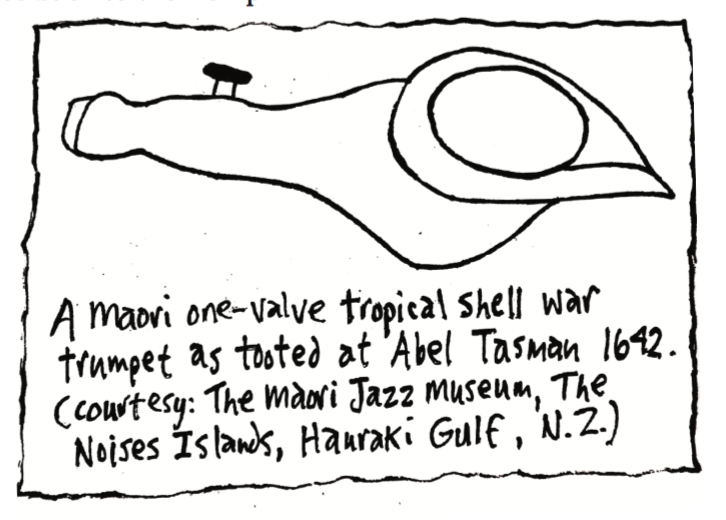

Two Maori war canoes head out towards the Dutch ships blowing what seemed to the Dutch to be “Moors trumpets” (shell horns). A Dutch seaman with a B-flat harmonic bugle, trumpets back at them a few bars from the opening of “Fanfare For The Dutch Fleet”, but the Maori canoes turn around and head back to shore (to get the rest of their instruments the Dutch seaman thinks).

The next day (19 December 1642), a Maori canoe with 13 paddlers in it comes close to one of the Dutch ships, is invited to come aboard with the offering of trade goods, but also turns around and heads back to shore. Shortly after however nine Maori canoes paddle straight out to the other Dutch ship and begin climbing aboard. Tasman sends a small boat with seven Dutch seamen in it to warn the other ship, but the small boat is attacked by several Maori canoes. It is rammed, four Dutch seamen are killed, and the Maori take the body of one of them and return to shore with the Dutch firing at them and the three other Dutch seamen swimming for their lives back to their ship.

When 11 more Maori canoes set out to attack the Dutch ships again, the Dutch shoot at them, kill one Maori, and sail out of Golden Bay. (Tasman calls it “Murderer’s Bay, we could not expect to make here any friendship with these people”.)

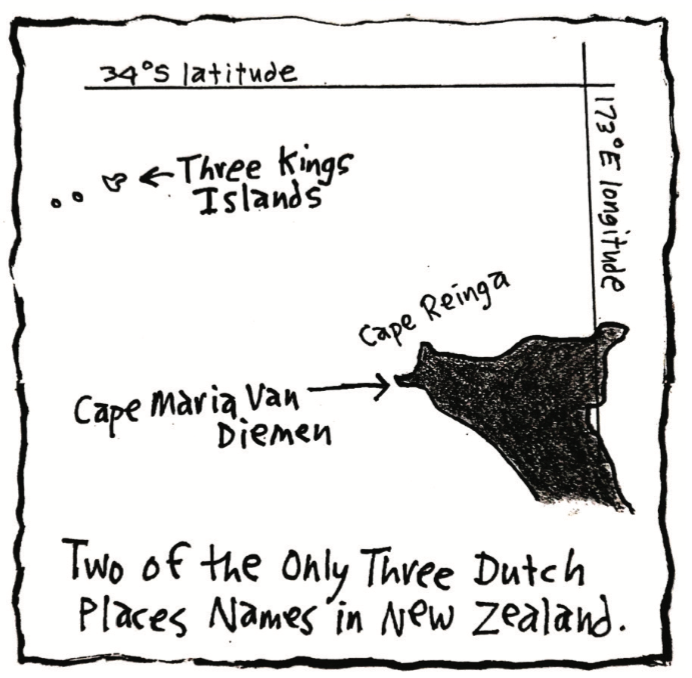

Tasman continues sailing north along the west coast of the North Island, passes Cape Maria Van Diemen at the far north tip, and arrives at Three Kings Islands where they want to land but see “35 gigantic natives with clubs in their hands”, and decide not to.

On 6 January 1643, Abel Tasman sails north away from New Zealand, never having stepped foot on it (but trying twice), and never to return (no other Dutch explorer goes back to New Zealand either).

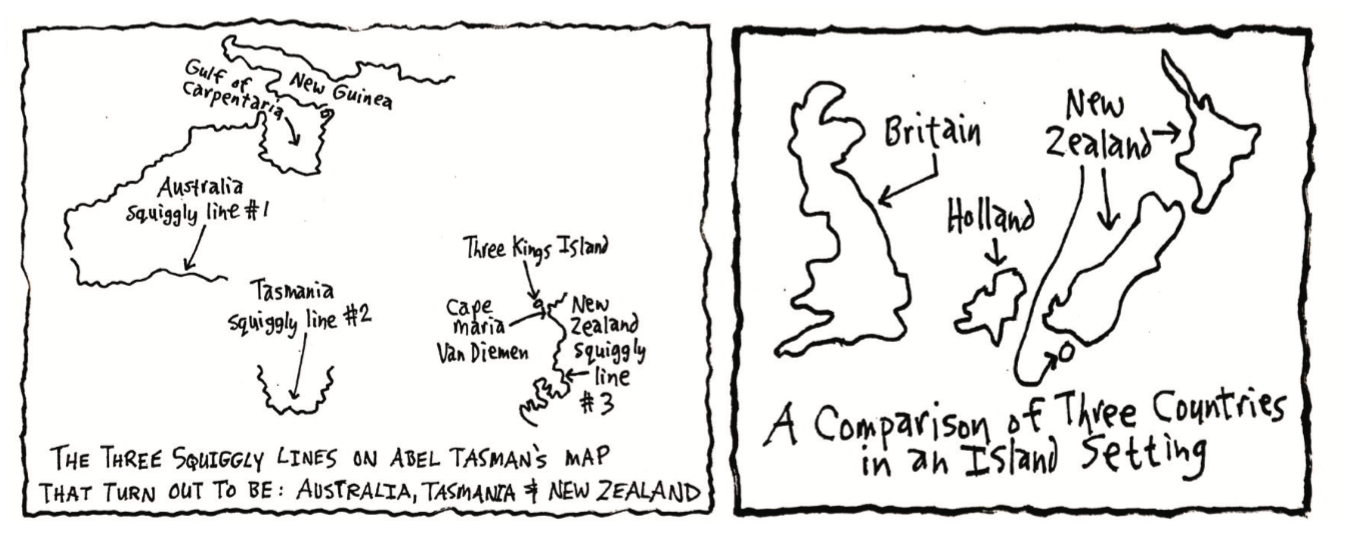

Having sailed along the shore of New Zealand for only 24 days however, Abel Tasman makes quite a contribution to the history of New Zealand. He plays an indirect part in giving it its name; he leaves it with 11 Dutch place names, three of which survive today thanks to James Cook (Cape Maria Van Diemen, Three Kings Island, Tasman Bay); and most importantly of all, he locates New Zealand on a map as a squiggly line floating all by itself out in the Pacific Ocean, a line that will stay a line until James Cook reasons that the line must have some other sides to it, and finds them 129 years later.

When Tasman goes back to Jakarta, Anthonie Van Diemen is not pleased. Although Tasman has found two new lands and named one after him (“Van Diemen’s Land” later Tasmania, Australia), and a cape on the other one after his wife (“Cape Maria Van Diemen”, New Zealand); he has not solved the New Guinea-New Holland mystery that he was sent out to do. Van Diemen dies in 1645, and Abel Tasman is not sent out exploring again and dies in 1659.

The Dutch try to keep the discovery of their two new lands a secret. They have no plans to do anything with them, but they don’t want anybody else knowing about them either. But these new lands are marked as squiggly lines on maps.

The Dutch found Australia, named it New Holland, charted 55% of its coastline; but left it as a large, almost-rounded squiggly line on a map with a north, west and south sides, but blank to the east.

Tasman found Tasmania, named it Van Diemen’s Land, and Staten Landt, which eventually became New Zealand; but left them as small squiggly lines on a map all out on their own in a big ocean.

Gradually though, over the years, other mapmakers in other countries see the Dutch maps and put the Dutch squiggly lines on their maps too. By 1744 the British know all about Nieu Zeeland, a squiggly line in the South Pacific Ocean in the vicinity of 40oS latitude. And the French know about it as well.

The Maori of New Zealand (as yet without their name), and Tasman’s squiggly line on a map representing Nieu Zeeland, have no more visits from white turnips or anybody else we know about, for another 126 years. The dead body of Tasman’s sailor that was carried away at Golden Bay, has long since been examined, dissected, eaten and reduced to souvenir trophies of bones. No Maori is alive who saw Tasman’s ships, and the story of their brief stay in Golden Bay becomes part of the oral history of the tribe that Tasman met (thought to be extinct by the time Cook got there).

And then 126 years later, within the same month of the same year of 1769, New Zealand has not one but two more visits from white turnips: one French (le turnip blanche), and one British (the ones who bestow upon themselves the white turnip name).

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One