Table of Contents

At Cape Runaway Cook sees for the first time the large double-hulled Maori war canoes who he has to fire on and run away from as they are decidedly not friendly. In the Bay of Plenty (which Cook thought looked fertile, cultivated and well-populated), the mood of the people is still unfriendly and he doesn’t land. Canoes come out, take their presents, help themselves to the sailors’ washing hanging out over the sides of the ship, throw stones at them, and promise that they “will kill us all in the morning”. Charming. Then they try a sneak attack that night on the ship and have to be driven off. Cook is learning about the complicated nature of the Maori (3 November).

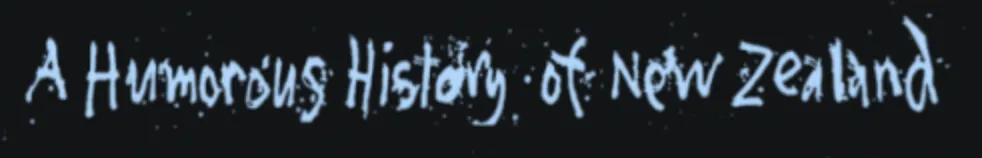

They don’t land anywhere again until Mercury Bay on the Coromandel Peninsula. Here they find a safe harbour, fresh water, and friendly people, and stay 11 days cleaning the ship, surveying the coast, observing the Maori hill forts and weapons (which Cook is much impressed with), and taking formal possession of this land in the name of the King by inscribing the ship’s name and date on a tree.

It is here too that Cook sees for the first time that the Maori eat human flesh (“the flesh was to them a dainty bit”), and he gives them potatoes to plant in the hope that they might eat these instead of people (they do, but only as a starter to the main course of barbecued humans).

Unfortunately another Maori is killed by the British, again for seeming to agree to a trade, but then taking what is offered and giving nothing back. Cook is not pleased with these deaths, but these Maori remain friendly with him and blame the dead man himself for his own fate (15 November).

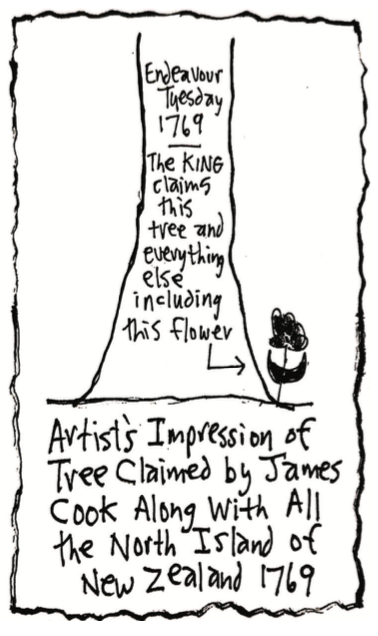

At Cape Colville and the river at Thames (Waihou) the Maori are friendly, but at Bream Bay and Cape Brett they aren’t. Before reaching North Cape (14 December), Cook passes and names Doubtless Bay where de Surville lands on 16 December. He charts the positions of Tasman’s Three Kings Islands and Cape Maria Van Diemen (he has Tasman’s maps and keeps these names on his charts as a tribute to Tasman), and then sails down the west coast of the North Island, sighting and naming Mount Egmont (6 January 1770), and putting into Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte’s Sound at the top end of the South Island (15 January 1770).

Here Cook finds fresh water, wood, fish and vegetables; but not very friendly people. They throw stones at them, eat humans and dogs, and seem poorer than the people to the north. Despite the inhospitable neighbours however, the advantages of Ship Cove outweigh the disadvantages, and it becomes Cook’s favourite refuge in New Zealand.

At Ship Cove Cook climbs hills and sees Cook Strait and the open ocean, realises that New Zealand is two separate islands, and decides to sail through the strait and prove it. Before leaving however he also claims this southern land for the King too (31 January 1770, toasting the Royal Family and giving the Maori the empty bottle).

Leaving Ship Cove he sails south towards Cape Campbell, South Island; then east to Cape Palliser, North Island; then north up the east coast of the North Island to Cape Turnagain; thus completing a counter-clockwise circumnavigation of the North Island and proving it is an island and not a continent (some of the crew had bet continent).

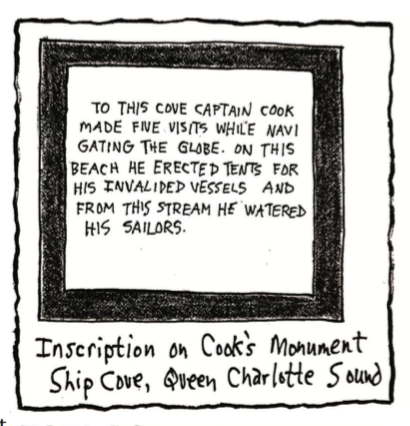

Back at Cape Campbell, Cook starts off on a clockwise circumnavigation of the South Island (of course he doesn’t know at this point that it is an island for sure): reaching Kaikoura (14 February); Banks Peninsula (16 February, he mistakenly calls it an island and not a peninsula); South Cape (8 March, he mistakenly calls Stewart Island a peninsula and not an island); Solander’s Isle (10 March); Dusky Sound; Cascade Point (16 March); Cape Fowlwind (20 March); Cape Farewell (23 March); Stephens Island (26 March); and Admiralty Bay (30 March); thus proving that this southern land is also an island.

Cook leaves New Zealand on 31 March 1770 to go east to try and find Tasman’s squiggly line of Van Diemen’s Land, misses it (Tasman had it located 3o too far to the east), and finds the east coast of Australia instead.

On his first trip to New Zealand Cook lands at six places on the North Island and two on the South, spends seven weeks ashore, collects 400 new plants, recommends New Zealand as suitable for settlement (especially the Bay of Islands and the river at Thames), and gives the Maori their name and their first written word in the English language. (It is thought the word “Maori” came from “tangata whenua”, which Cook sounded out and wrote in English as “Maori”.)

Between Cook’s first and second visits to New Zealand (1770-1773), New Zealand is visited again by the French. Marion Marc-Joseph du Fresne (or Dufresne), sights the west coast of North Island (25 March 1772), lands in Spirits Bay and Tom Bowling Bay (east of North Cape, April), and puts into The Bay of Islands (11 May 1772). Unfortunately, after one month of living peacefully with the Maori, Du Fresne and 26 others are killed and eaten. A search party of 12 is sent out to look for them, and only one returns alive. The rest of the crew attack three Maori villages, kill 200-300 Maori, and leave (June 1772).

Cook makes two other trips to New Zealand (1773-74, 1777), staying 17 days, distributing seeds and domesticated animals to the Maori of Table Cape, and leaving notes buried in a bottle attempting to rendezvous at Ship Cove with Tobias Furneaux (who while at Ship Cove waiting for Cook has 10 men killed and eaten by the Maori while out gathering “greens” in Grass Cove).

In all his three voyages and four visits to New Zealand, Cook spends 328 days there recording the resources of flax, timber, seals and whales that will attract future visitors; introducing the Maori to metal, potatoes and muskets; accurately mapping the islands to within 7% of one degree of accuracy (remarkable); providing New Zealand with more of its English placenames than anyone else (as well as preserving the three Dutch ones); and bestowing upon the Maori their name. But, as Kupe found, nobody is in any real hurry to get back to New Zealand, although it’s only 11 years between visits this time and not 400.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part Two

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Three

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.