Table of Contents

David Bell

David Bell, senior scholar at Brownstone Institute, is a public health physician and biotech consultant in global health. He is a former medical officer and scientist at the World Health Organization.

Public health responses are most effective when they are grounded in reality. This is particularly important if the response is intended to address an ‘emergency,’ and involves the transfer of large amounts of public money. When we reallocate resources, there is a cost, as the funds are taken from some other program. If the response involves buying lots of products from a manufacturer, there will also be a gain for the company and its investors.

So, clearly, there are three obvious requirements here to ensure good practice:

1. Accurate information is required, in context.

2. Those gaining financially can have no role at all in decision-making.

3. The organization tasked with coordinating any response would have to act with transparency, publicly weighing costs and benefits.

The World Health Organization (WHO), tasked by countries to help coordinate international public health, has just proclaimed Mpox (monkeypox) an international emergency. They considered an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and nearby Central African countries to be a global threat, requiring an urgent global response. In declaring its emergency, WHO stated there were 537 deaths among 15,600 suspected cases this year. In its 19th August Emergency Meeting on Mpox, WHO clarified its figures:

…during the first six months of 2024, the 1854 confirmed cases of Mpox reported by States Parties in the WHO African Region account for 36% (1854/5199) of the cases observed worldwide.

The WHO reiterated that there had been 15,000 “clinically compatible” cases, and about 500 suspected deaths. The implications of these 500 unconfirmed deaths, equaling just 1.5 per cent of the malaria deaths in DRC over the same period, are discussed in a previous article.

Journals such as the Lancet have dutifully towed the WHO’s ‘emergency’ line, though intriguingly noting that the mortality could be far lower if “adequate care” had been provided. Africa CDC agrees, with more than 17,000 cases (2,863 confirmed) and 517 (presumably suspected) deaths of Mpox have been reported across the continent.

Mpox is endemic to central and west Africa, being present in species of squirrels, rats, and other rodents. While it was identified in monkeys in a Danish lab in 1958 (hence the misnomer ‘monkeypox’), it has probably been around for thousands of years, causing intermittent infections in humans between whom it is spread by close physical contact.

Small outbreaks in Africa mostly went unnoticed by the rest of the world, mainly because they were (as now) small and confined. Mass smallpox vaccination may also have suppressed numbers still further a few decades ago, as smallpox is in the same Orthopoxvirus genus of viruses. So, we may be seeing an upward trend of this generally milder illness (fever, chills, and a vesicular rash) over recent decades since smallpox vaccination ceased. The Smithsonian magazine put an informative summary together in 2022, after the first out-of-Africa outbreak which was spread by sexual contacts within a limited demographic group.

So, here we are in 2024, on the tail of a massively profit-driving (and impoverishing) outbreak called Covid-19 that enabled the largest transfer of wealth from the many to the few in human history. The WHO’s announcement that 5,000 (or less) suspected Mpox cases is a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) allows it to fast-track vaccines through its Emergency Use Listing (EUL) program, bypassing the normal rigor required to approve such pharmaceuticals, and is suggesting Pharma start lining up.

At least one drugmaker is already discussing a supply of 10 million doses before year-end. The business case for this approach, from the corporate viewpoint, is well-proven. So are the harms in countries like DRC, as a mass vaccination program of this nature requires redirection of millions of dollars and thousands of health workers who would otherwise be addressing diseases of far larger burden.

The WHO is a large organization, and while some there have been on the hustings asking for money, others have been working hard to accurately inform the public (a core responsibility of the WHO, which retains some dedicated people). Like much of the WHO’s work in the past, this is thorough and commendable. Some of this information is summarized in the following graphics:

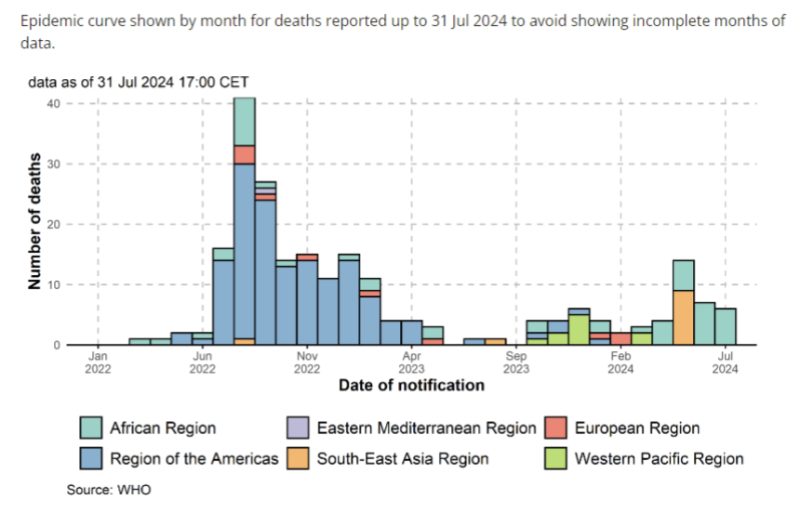

These charts provide data on confirmed cases, where someone with somewhat non-specific symptoms has been tested and shown to have evidence of Mpox virus in blood or secretions. Clearly, not everyone suspected can be tested, as Mpox is a very small issue for people facing civil wars, mass poverty, and vastly more dangerous diseases.

However, the WHO has absorbed a lot of money for outbreak investigation, and so have partner organizations, so we can assume there is a fairly good effort going on to detect and confirm numbers (or where has this money gone?).

In the past 2.5 years, the WHO has confirmed 223 deaths in the whole world, with just six in July 2024 (the time when the WHO Director-General warned the world of a rapidly increasing threat). Note here that 223 deaths are just 0.2 per cent of the 102,997 confirmed cases. In Africa, just 26 deaths have been confirmed in 2024 among 3,562 cases (0.7%), spread across five countries (and 12 countries with cases). They are influenza-like mortality rates, not Ebola-like.

As severe cases are more likely to be tested than mild cases, the infection fatality rate may be far lower. We also don’t know (though someone does and should tell us) what the characteristics of those dying are. Most in Africa are reported to be children, so it is likely they are malnourished, otherwise immunocompromised (e.g., HIV), and have susceptibilities that could be addressed.

As is obvious from the third graphic below, nearly all the global deaths listed above were from the previous outbreak in 2022. This was a different clade (variant) and mostly occurred outside of Africa.

It is important to note a few things here. It is difficult to confirm all cases in areas with poor infrastructure and security. Mpox symptoms and signs are also frequently mild and overlap other diseases (e.g., chickenpox or even flu) so many cases may go unnoticed. Notification of results can also lag. However, the 19 confirmed DRC Mpox deaths amongst roughly 40,000 DRC malaria deaths so far this year is about one versus 2000. Whichever way you count it, it is not going to become much more significant. That is what the new international emergency looks like in actual data, or if you are the population of DRC at Mpox ground zero. It is likely you would not notice anything at all.

Why has the WHO declared an international emergency? Some claim it helps mobilize resources, which is a bit pathetic. Firstly, grownups should be able to discuss a situation that has persisted for two years in a rational manner and decide what might be needed, without banging a drum. Secondly, an outbreak that is killing a tiny fraction of malaria (or tuberculosis, or HIV) deaths, and far less than those currently dying in war, may not be an international emergency.

And what should be done? Diverting resources from DRC’s major priorities would undoubtedly kill far more than are currently dying from Mpox. It is quite probable that direct adverse events from vaccination alone will kill more than the 19 DRC Mpox victims confirmed this year. We likely undercount Mpox deaths, but we also undercount pharmaceutical deaths.

Perhaps a useful response would be to improve immune competence through nutrition, providing very broad benefits (but completely failing in terms of Pharma profit). Gavi’s half-billion dollars would provide vast and broad-based benefits if applied to sanitation. Perhaps limited, well-targeted vaccination may also help some communities, but there is no business case for such approaches.

What is clear, as noted above, is the following:

1. The data on Mpox, and other competing priorities, must continue to be shown in context, along with costs and opportunity costs of the response.

2. Those who will gain financially from vaccinating millions of people must not be part of the decision-making process (whether or not such a huge resource transfer can possibly be supported for such a small disease burden).

3. The WHO should continue to act with transparency, as the public has an absolute right to know what they are paying for, and the harm (and perhaps benefit) they can expect from it.

The number of Mpox deaths will rise as more are infected, and perhaps as some suspected cases are confirmed. However, we are facing a small problem in an area with far larger ones. It is posing low local risk and minimal global risk. It is not a global emergency, by any sane, rational, public health-based definition.

The rest of the world can respond by sending vaccines and lots of foreigners who need looking after, diverting local health and security personnel and almost certainly killing more DRC residents overall. Or, we can recognize a local problem, support local responses when local populations ask, and concentrate, as the WHO once did, on addressing the underlying causes of endemic disease and inequality. They are the things that make the lives of people in DRC so difficult.

This article was originally published by the Brownstone Institute.