Table of Contents

Janet Taylor

MSc (Nutr. Sci)

Janet has two completed PhD projects in Nutritional metabolic (Medical) science. She is passionate about food, farming and human health.

The fart tax seems to diminish the fact that gut methanogen organisms are responsible for ruminant animal carbon GHG emissions, and that the combined C and N farmer burdens include animal urine and dung, and fertiliser per hectare.

Sheep farmers seem to be faring worst in the preferred scheme of GHG accounting, with no mention of plant or soil organism contributions to the emission factor (EF) calculations by MPI.

Sheep tread lightly on this good green earth, but perhaps the accounting is skewed. Analysing the MPI reference for nitrous oxide (N2O) EFs (Kelliher et al, Environmental Pollution, 2014) shows some theoretical holes that forgive dairying in the farm EF equations that are based on export value of milk and meat.

There are a few crucial guesses involved in this farm accounting, like the eyeometer used to determine metabolisable energy of dairy cow body fat, the one sheep N and C reference from Inner Mongolia (Ma et al, NZ Journal of Agric Research, 2006), and soil drainage (two choices: free or poor) based on soil colour. And farm hill slope made no statistical difference to animal N excretion but researchers carried on including this variable in their models anyway.

We are to assume that European data (n=846 field trials) which sets fertilizer N and C farm contributions globally, can be reduced by half for NZ’s urea (CH4N2O) farm emissions, based solely on MPI model predictions.

Nearly 200% more N/hectare is deposited on dairy farms than sheep farms from animal urine plus urea fertiliser, but the models cannot explain why fertiliser affects the cow EF but not the sheep EF when urine N emissions for all animals are the same. By leaving out the natural C and N cycling between plant root tips and soil organisms, and by ignoring stocking rate and its urine effects on drainage, we disadvantage regenerative farming practices and favour intensified commercial operations with no N and methane (CH4) inputs from grazing.

Our Minister for Agriculture reckons ‘farmers have many other options for land use’ and that research is ‘developing solutions such as a bolus’. A gob of food laced with inhibitors will have metabolic consequences apart from methane output in gut organisms. Do we know the effects a medicated bolus might have on animal protein deposition when these methanogens are blocked from vitamin B12 production?

In other words, is our fixation on carbon at the expense of other more important factors in animal health and meat/milk production?

Federated Farmers has lobbied for farmer-based emission costs because at the food processing level it would be ‘unworkable, unscientific, and a burden on consumers’. But animals don’t become meat and milk exports until after being processed into food. Allowing the likes of Fonterra, our largest coal importer for the milk dehydration process, to claim GHG outputs as manufacturing costs skews agricultural emissions burdens.

The current lack of workable solutions for farmers may be a product of the type of science we focus on. Animal dietary nutrition may have a greater effect on gut methanogen output than animal genetic manipulation. And the 1980s dry matter digestibility factors used to covert grass energy to animal protein in MPI models may limit our scientific vision.

NZ’s remit for agricultural research has included food production for 100 years, yet we have focused predominantly on genetics to enhance milk and meat volume.

Our food prices include manufacturing costs, yet the nutritional value is all due to the farmers and their land management.

Full-fat dairy intakes have now been shown to reduce cardiovascular disease risk.

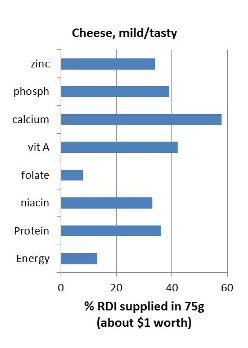

Global scarcity of food nutrients such as calcium, vitamin A and zinc, as well as the fat-soluble vitamin D accrued from animal grazing, give added value to our meat and milk exports. Animal-based foods provide nutrient-dense value per farming hectare as opposed to plant food production.

Are we looking in the right place for scientific evidence that supports farmers in changing times?