Table of Contents

Some years ago, I worked in education support at a Year 11/12 school. I was shocked to hear teachers so often complaining of students who could barely read or write. Then I studied journalism at university — and was even more astonished to continually read other students’ work riddled with spelling and grammar mistakes.

How on earth could anyone finish 10-12 years of schooling and still be barely literate or numerate? How could someone study an undergraduate course entirely based on reading and writing, and yet have such appalling English standards?

How can this happen in a modern First World country? It’s actually easy to understand.

First, many students, particularly in remote areas of the country, are chronic truants […]

Chronic truancy can exist for a number of reasons. The state system I worked for had a teaching assistant attached to each school, called a Home Liaison Officer, whose job it was to follow up on such absences. I asked ours about a week later about Jimmy [a chronic truant]. “His mum told me to go away”, she said. He had previously attended school for eight days in Year 8.

So, was Jimmy kept down at the level at which he last regularly attended school?

If Jimmy had returned – maybe he did – at the beginning of the next year, he would automatically be placed in the next grade. How he could possibly handle Year 10 English? But this would not have been asked. He would have been placed without question in a class, there to flounder and grow further discouraged, which would likely encourage him to skip school again.

Easier to just rubber-stamp and let him “progress”. Except that he was never going to progress in any meaningful way.

Learning progresses sequentially. In primary school English, for example, students learn words, then sentences, and how a single-strand story progresses: “Jane runs. Jane runs up the hill,” and so on. “Chapter books” follow, and by the end of primary school capable students are beginning to head into the world of multiple-strand narratives, flashbacks, and other literary devices […]

Promoting students by age without ensuring that they have the necessary skills is condemning them to a life of low education, and all that comes with it. They will likely have lower incomes through not being able to attain the necessary qualifications – not being able to properly read technical manuals – as well as a lesser lives through not being able to understand books, comics, films and so much more.

It’s no surprise that when the author talks of “remote areas”, he’s really talking about Aboriginal students. For all the palaver about “closing the gap”, the gap will never be closed so long as Aboriginal kids are set up to fail by never being asked to go to school and learn.

But it’s not just Aboriginal kids. Even in the suburbs, non-Aboriginal kids are being similarly rubber-stamped up through the system until they can finally be let go — and settle into a life on welfare. Maybe these kids aren’t chronic truants, but they might as well be, for all they’re actually learning.

It would be kindness, not cruelty, to hold back such children if they can’t pass a national benchmark test. Schools used to have such a concept, especially for the leaving of the primary system, but over the years it has been dropped. The main reason seems to be so as not to harm a child’s “self-esteem”.

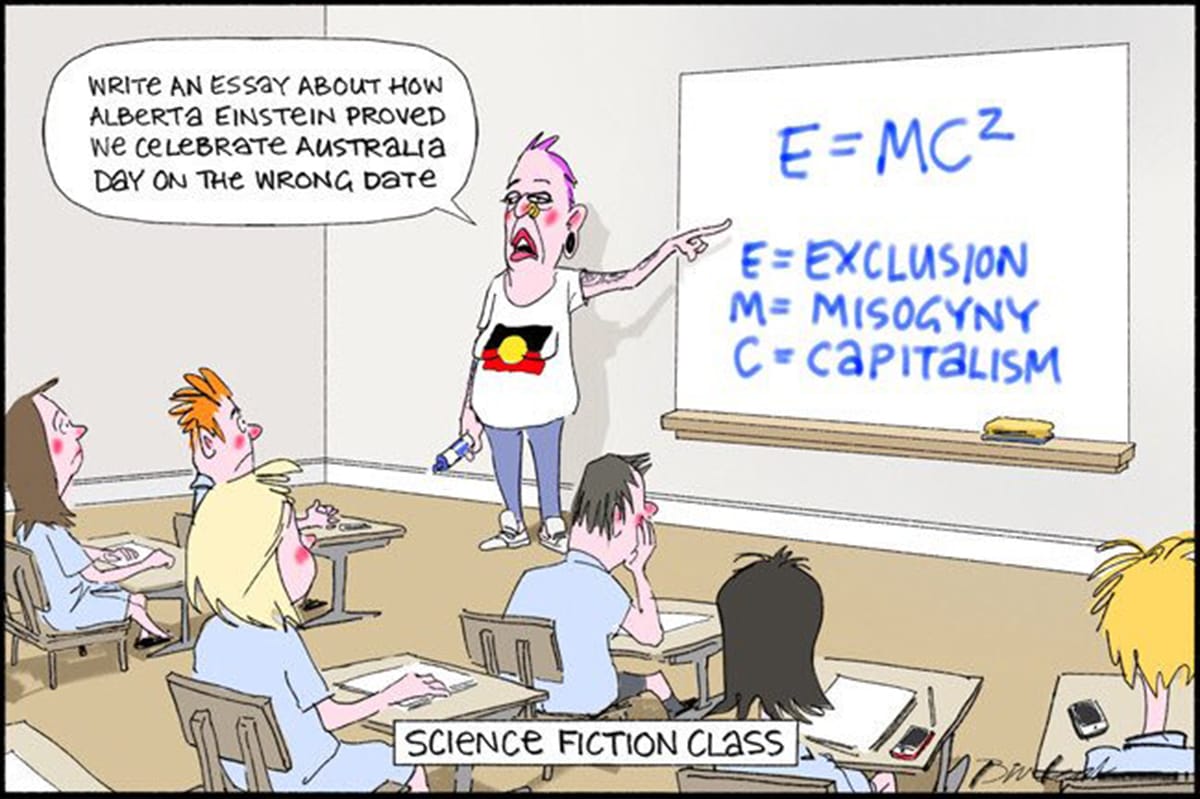

This is the same thinking that wants to eliminate red pencilled marking, or even the very concept of marking students’ work at all. Teachers’ unions vociferously oppose national bench-marking and standardised testing. Whose self-esteem are they really protecting?

But the present system merely delays an absolutely massive battering to self-esteem: the huge blow to one’s ego through discovering an apprenticeship is not possible, nor is anything else that matches qualifications to a better job and higher pay.

Quadrant Online

Singapore is beating the pants off Australia and New Zealand at education. It sets criteria and benchmarks all the way through a child’s education, from the Primary School Leaving Examination on — and expects them to be met. Australia has the ATAR, which isn’t assessed until students actually finish high school, long after the damage has been allowed to be done.

As furiously as teacher unions oppose it, performance-based pay starts to sound more and more like a good idea. Even more useful would be tying parents’ welfare benefits to their child’s school attendance.