Table of Contents

Michael Cook

Michael Cook is the editor of MercatorNet. He lives in Sydney, Australia.

Earlier this month, the Australian Government announced a A$15 million pilot program for mitochondrial donation, or, as it is sometimes called, “three-parent IVF”.

In December 2021, Parliament passed Maeve’s Law, which permitted the controversial procedure. It is legal in the United Kingdom and Singapore but almost nowhere else. It is also being marketed by shady IVF clinics in Greece and Ukraine (and perhaps other countries) where there is little regulation. In the United States the Food and Drug Administration has effectively banned it.

Mitochondrial defects are responsible for a number of genetic diseases; some are quite serious and leave a child with painful disabilities like blindness and epilepsy and a low expectancy. The Prime Minister in 2021, Scott Morrison, strongly supported the legislation. “I’m a person who has strong religious beliefs as well but it presents no difficulty for me on this issue,” he told The Australian. “And I think the compassionate thing to do here is to find a way where if we can avoid that horrific, horrific suffering then I believe we should.”

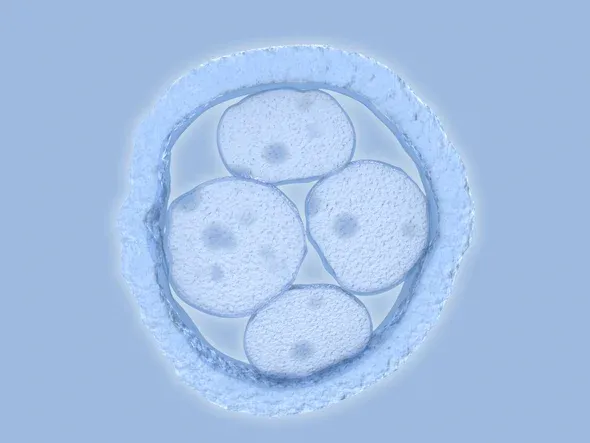

Mitochondria are organelles floating in the cell cytoplasm that generate energy and are vital for the healthy functioning of the cell. The idea of mitochondria replacement therapy is to replace defective mitochondrial DNA in one woman’s egg with healthy mDNA from a second woman. There are a couple of technically complex ways to achieve this with IVF.

In controversies in the media and in legislatures, the procedure was defended as “lifesaving” – although the only lives to be saved would be of children yet to be born and numerous embryos would inevitably be destroyed.

Very few babies have been born using the technique. In the UK, only Newcastle University has been authorised to use it, but it has not reported any births.

Although they were swept aside, Australian critics raised a number of safety and ethical concerns about mitochondrial donation. They were ignored. The bill sailed through the House with a vote of 92 votes to 29, and through the Senate by a margin of 37 to 17.

However, MIT Technology Review has just revealed some unsettling results – sometimes the defective mDNA re-emerges in the baby’s cells, an event called “reversion”. It has only happened twice in a handful of births; nonetheless scientists are disturbed. In one case “the proportion of mitochondrial genes from the child’s mother has increased over time, from less than 1 per cent in both embryos to around 50 per cent in one baby and 72 per cent in another.”

In both cases, the mitochondrial transfer had been used as fertility treatment rather than to avoid passing on a genetic disease, so neither baby was at risk. But the reversion has put a big question mark over the procedure. “The scientists behind the work believe that around one in five babies born using the three-parent technique could eventually inherit high levels of their mothers’ mitochondrial genes.

For babies born to people with disease-causing mutations, this could spell disaster—leaving them with devastating and potentially fatal illness.”

Joanna Poulton, a mitochondrial geneticist at the University of Oxford, told the magazine that even a 20 per cent risk of reversion was worrying. “There are mutations where quite low levels can cause problems,” she says. For some diseases, the level can be as low as 15 per cent, she says.

And Heidi Mertes, a bioethicist at Ghent University, said that “Scientists knew beforehand that the trials were never going to be risk free, and that they involve a potential waste of perfectly good donor eggs and embryos. ‘In the end, you’re presenting an option to patients that is more dangerous than their alternative,’ she says.”

In other words, it is possible that parents are being deceived. After all the effort and anxiety involved in mitochondrial donation, one in five children will inherit the disease anyway. The miracle was fake news.

Is this a problem? If the technique is too dangerous, parents simply won’t use it.

Yes, it is.

Apart from crushing the hopes of would-be parents, the problem is that the legislation has set dangerous precedents. First, Maeve’s Law permits the creation of IVF embryos (children) with three parents. This is unprecedented in Australia. Second, it permits a kind of modification of the human genome, as any changes which are inadvertently introduced will be inherited. This has been banned by international conventions.

Not for the first time, scientists and lobby groups pulled the wool over MPs’ eyes, by dangling before them the tantalising prospect of miracle cures. They dutifully voted to incorporate significant changes into Australian law and then … ooops, we goofed. It doesn’t work ... but with a few more grants, we’ll find a solution.