Table of Contents

Growing up as a more-than-usually dinosaur-mad kid in Australia in the ’70s, it often seemed that Australia was the dullest place in the world when it came to fossils. All the really exciting finds seemed to be in Europe and North America. But that was merely an artefact of ‘discovery bias’: most of the research at that time had been confined to those two continents.

Even then, though, Australia was unveiling unique treasure troves of fossils, such as the Ediacara fossils discovered in South Australia in 1946, with their vast array of preserved fossils from the until-then relatively unknown Pre-Cambrian eras. Later discoveries, such as the Dinosaur Cove site in the 1980s, showed that Australia’s fossil sites rival, if not exceed, anything else in the world.

The discoveries are still coming. New research in Queensland has provided the first hard evidence of what was merely assumed for the past 150 years: that the sauropod dinosaurs were herbivores.

Sauropods were the giant species like Brontosaurus, Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus: characterised by massive bodies and extremely long necks and tails. What? I hear you say: Didn’t we always know that they were herbivores? Despite the certainties about ‘vegiesaurs’ in movies like Jurassic Park, that these dinosaurs were indeed herbivores was previously inferred from such evidence as their flat teeth, suited to grinding tough plants, and huge body that would have made it hard for them to chase down moving prey.

But direct, hard evidence of their diet was always missing – until now.

Now, in today's issue of the journal Current Biology, researchers report their first ever discovery of fossilised intestinal contents — referred to as “cololite” – from a sauropod.

The cololite was found inside a relatively complete skeleton of Diamantinasaurus matildae in 2017 at Belmont Station, near Winton, with much of it sealed over by a layer of mineralised skin.

This joins a host of exciting recent discoveries, such as preserved remains of a predatory dinosaur’s victim in its stomach, an ankylosaur preserved almost perfectly in three dimensions (including traces of its original skin colour), and even a dinosaur’s perfectly preserved bumhole (which proved that at least some classes of dinosaurs had cloacae, like modern birds).

“What was really exciting about it [the gut fossil] is in places you could see the folds of the gut,” Belmont Station owner and palaeontologist David Elliott said.

An analysis of the fossil showed a young Diamantinasaurus specimen, nicknamed “Judy” [after Dr Elliott’s wife], whose gut contained small voids – impressions left behind by decomposed plants.

Palaeontologist and study lead author Stephen Poropat, from Curtin University, said Judy seemed to have eaten plants from a range of heights.

“There’s relatives of modern-day monkey puzzle trees, we have seed ferns, which are a totally extinct group,” he said.

“And we also have leaves from angiosperms, which are flowering plants. Back in the Cretaceous period when Judy was alive, they would have looked somewhat similar to modern-day magnolias.”

The preserved gut contents also supported another long-suspected fact: that sauropods fermented their food in their stomachs, rather than chewed it.

Because the fossil is of an ‘adolescent’ Diamantinasaurus, it also provides insight into how sauropod feeding habits would have changed as they grew.

Dr Poropat […] theorised Judy (who is referred to as “she” although her gender isn’t known) was in a transition phase where she was eating some of the plants she consumed when she first hatched.

“We actually speculate that Judy might have had a diet different to an adult Diamantinasaurus,” he said.

“She couldn’t reach up into the tops of conifers, but also she’s starting to eat the conifer foliage that is targeted maybe more so by adults.

Sauropod expert, Cary Woodruff of the Miami Frost Museum of Science, said that finding a fossil in this ‘transitionary’ age, made the discovery particularly important.

“Previous studies have shown that in some species, the young had pointed snouts, likely for selective feeding, and when they grew up, they had broad ‘muzzles’ for grazing,” he said.

“And in some, the young had teeth designed for both soft and coarse vegetation.

“Imagine a Swiss Army knife in your mouth; no matter the plant, you have the right tool for the job.”

Dr Woodruff said Judy captured a “moment in time” where the Diamantinasaurus had this Swiss Army knife.

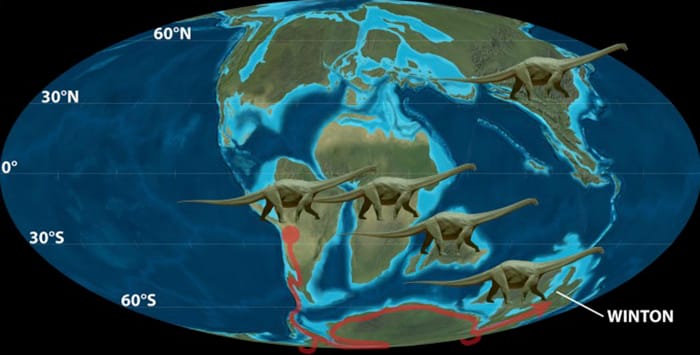

Diamantinasaurus, first discovered in 2009, lived between 101 to 94 million years ago, in the mid-Cretaceous period, roughly in the middle of the sauropods’ long existence.

When Diamantinasaurus lived, Australia was closer to the South Pole, and what is now outback would have been a wet flood plain covered in conifers, gingkos, seed ferns and other plants – plenty of food for a growing dinosaur.