Table of Contents

Michael Cook

Michael Cook is editor of Mercator.

There are one million frozen embryos in IVF clinics across the United States and they are all “extrauterine children”. That is the stunning opinion handed down last week by the Alabama Supreme Court and it has sent shivers up and down the spine of the IVF industry.

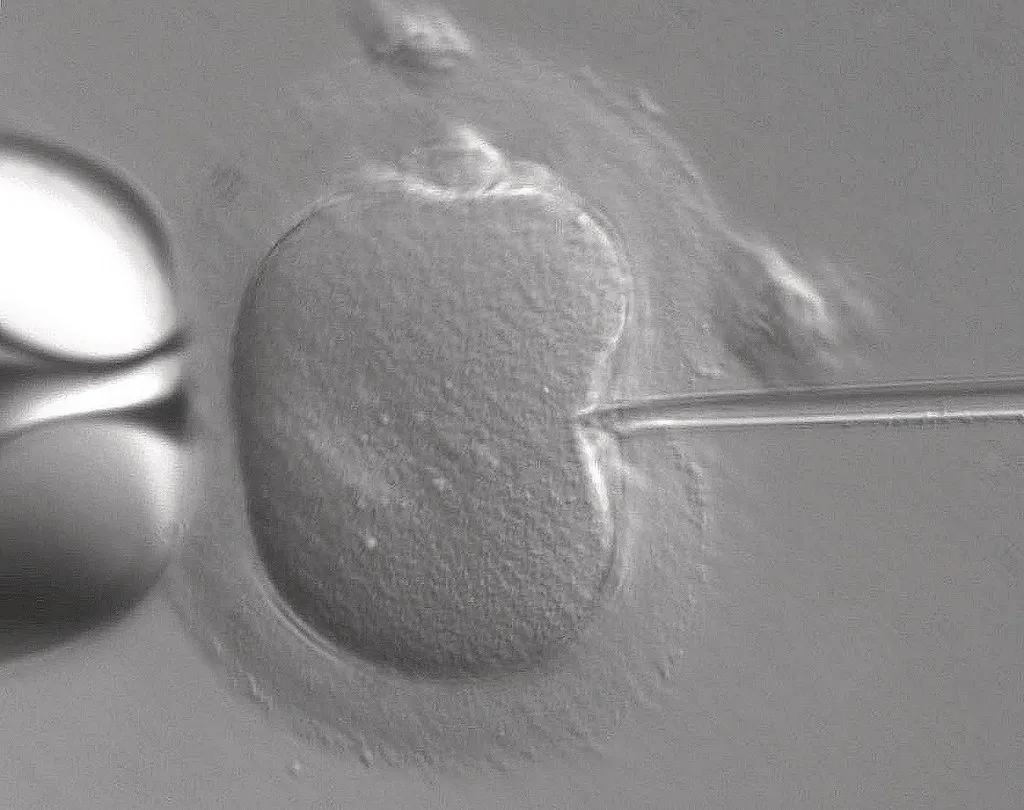

The case, Burdick-Aysenne v. Center for Reproductive Medicine, was brought by three couples whose embryos had been destroyed in a bizarre accident in the city of Mobile. A patient wandered into the embryo storage area of the fertility clinic through an unsecured door, opened the freezer and removed a container. Since embryos are kept frozen at about -196° Celsius (-321° Fahrenheit), the patient suffered freeze burns and dropped the container, killing the embryos.

The parents then sued the clinic for wrongful death under Alabama’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act. Both the parents and the clinic accepted that an unborn child is a “human life,” “human being,” or “person” – but is a frozen embryo one as well? In the words of the court:

The question on which the parties disagree is whether there exists an unwritten exception to that rule for unborn children who are not physically located “in utero” — that is, inside a biological uterus — at the time they are killed.

The court decided by a vote of 8 to 1 that “extrauterine children” living in a “cryogenic nursery” are children. As Justice Jay Mitchell wrote for the majority:

This Court has long held that unborn children are “children” for purposes of Alabama’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act, a statute that allows parents of a deceased child to recover punitive damages for their child’s death. The central question presented in these consolidated appeals, which involve the death of embryos kept in a cryogenic nursery, is whether the Act contains an unwritten exception to that rule for extrauterine children — that is, unborn children who are located outside of a biological uterus at the time they are killed. Under existing black-letter law, the answer to that question is no: the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act applies to all unborn children, regardless of their location.

If they are “extrauterine children”, Alabama’s IVF industry will be forced to make radical changes in its practices. The sole dissenting justice said as much in his opinion: “the main opinion’s holding almost certainly ends the creation of frozen embryos through in vitro fertilization (‘IVF’) in Alabama.”

The University of Alabama at Birmingham health system has already pressed the pause button on IVF treatments. “We are saddened that this will impact our patients’ attempt to have a baby through IVF, but we must evaluate the potential that our patients and our physicians could be prosecuted criminally or face punitive damages for following the standard of care for IVF treatments,” a spokesperson said.

Even the White House joined in the lamentation. President Biden’s press secretary, Karine Jean-Pierre, said that the Alabama court’s decision would lead to “exactly the type of chaos that we expected when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and paved the way for politicians to dictate some of the most personal decisions families can make.”

Needless to say, the IVF industry was horrified by the decision. The president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Marina Gvakharia, said that it was unscientific:

From a scientific perspective, embryos represent a stage in the continuum of human development, but they do not possess the attributes of personhood. Recognizing this crucial distinction is paramount to ensuring that legal decisions align with scientific understanding and respect individuals’ reproductive rights.

What else would you expect? The whole IVF industry is based on the premise that the one million embryos in deep freeze are just blobs of disposable human tissue, not human beings. But, in any case, whether or not they are “persons” is a philosophical question which science cannot answer.

In Alabama, it is also a constitutional question which its Supreme Court has answered.

Impact on IVF industry

Will Burdick-Aysenne v. Center for Reproductive Medicine influence the practice of IVF elsewhere in the United States? Not immediately. The defendants are unlikely to appeal to the same US Supreme Court which was responsible for Dobbs. If they were to lose, the frozen embryos would become “extrauterine children” in “cryogenic nurseries” in the other 49 states.

Furthermore, section 36.06 of Alabama’s state constitution, which voters adopted in 2018, guarantees “the sanctity of unborn life and the rights of unborn children, including the right to life”. Most other states are not so committed to protecting the unborn.

The court’s decision does not ban IVF but it may force the industry to reassess the way it works. It is normal practice to create several embryos but only to implant one or more, with the others kept as “spares”, sometimes for years, sometimes for decades. There are other approaches to IVF which are more protective of embryos. Italy, for instance, only allows clinics to create three embryos and all three must be transferred. It has effectively banned cryopreservation of “extrauterine children”.

The Alabama court’s ruling ought to prompt a closer scrutiny of the global US$24 billion IVF industry. It recently embarked upon a charm offensive to lobby for insurance coverage and government subsidies for infertility treatment. Why? Because of a “catastrophic” decline in fertility rates around the world. It is touting IVF as a solution to demographic decline.

This claim is unproven. The best counter-example is Japan, where 5 per cent of births are IVF babies, one of the highest rates in the world. But Japan also has one of the lowest birth rates and may have entered a demographic death spiral. The problem may be that readily available IVF encourages women to delay having children. By the time they are ready, their biological clock has stopped ticking.

Undeterred by lack of evidence, the International Federation of Fertility Societies has created a website called “More Joy” to promote its services to a world where falling fertility threatens “economic growth and social stability”. “Together let’s ensure that everyone who wants to build a family can,” it says.

A growing segment of the market for fertility services is single women and gay and lesbian couples. That’s the reason why the ASRM insists that “family building” is a basic human right for everyone, regardless of marital status or sexuality. IVF has become a pillar of the LGBT lifestyle by enabling LGBT people to create children of their own.

The greedy and increasingly industrialised IVF industry has had a dream run since the birth of Louise Brown in 1978. It’s about time that someone questioned the assumptions which underpin it. The Alabama Supreme Court decision is a chance to open up that conversation.