Table of Contents

David Leyonhjelm

David Leyonhjelm was elected to the Senate in 2013 and 2016, resigning in 2019. He is the author of two books and has operated his agribusiness consulting company for over 30 years. He has degrees in veterinary science, law and business.

Most people accept that some things are legitimately the responsibility of the government while others are private matters. This is not new; in ancient Greece Aristotle described the public realm of the polis, state, city or republic as the site where people consent to or contest the laws, contracts, covenants, or principles of community that govern personal and social conduct. The private realm was defined by the hearth and home, remaining the place of family, comfort and individual identity.

There has always been debate about where the border lies and the overlap between the two. Anarchists argue there is no need for government at all, while communists believe the government should manage all aspects of our lives. Most people prefer something in between, with libertarians obviously being a lot closer to the anarchists than communists.

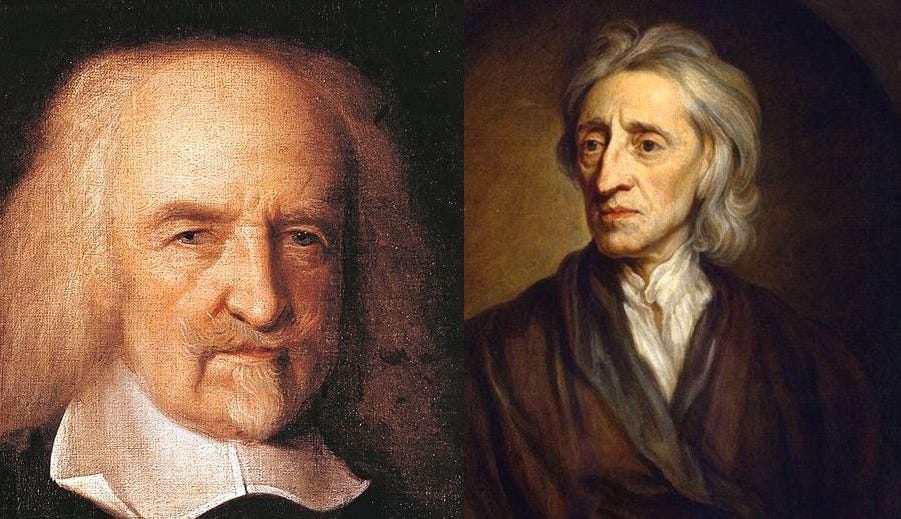

Much less often debated is whether anyone is wise enough or, as Friedrich Hayek would say, fatally conceited enough, to determine where the border lies. The views of two 17th-century English philosophers, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, help us to understand that question.

Hobbes believed the natural state between people was conflict, with life being ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’. He considered people were needy and vulnerable, easily led astray, with fragile capacity to reason. The only way to avoid a perpetual state of war of ‘all against all’, in his view, was to relinquish all rights to a sovereign. The sovereign dispensed justice and allowed such freedoms as considered appropriate while maintaining civil society, and could not be questioned.

Locke’s view was that people generally got along quite well when left alone, and in the natural state were equal and independent with a right to defend “life, health, liberty, or possessions”. However, he assumed this was not enough, so it was necessary to establish a society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government. Rights were only relinquished to the extent necessary for this to occur, and if the government ever retained more than necessary he favoured a revolution to restore the balance.

How we decide on the border between the public and private realms is governed.

Hobbes’ idea of an unaccountable sovereign has now been mostly replaced by what we know as democracy, in which we vote once every few years in the hope this will ensure the sovereign remains benevolent. But that does not answer the question: how to decide how much the government can do?

Those who share Hobbes’ view that humans are feeble minded and quarrelsome believe society cannot function without a strong government. They also claim that we have no inherent rights, since we derive everything from the government, and are also inclined to argue that everything is prohibited unless it is permitted.

Remarkably, those people also tend to believe that feeble mindedness only describes other people. This is confirmed by opinion surveys showing around two thirds regard themselves as having above average intelligence, an obvious mathematical impossibility. The Dunning Kruger effect, a cognitive bias that occurs when someone overestimates their knowledge or abilities in an area where they are not particularly knowledgeable, is another consequence.

When such people are in positions of authority, they typically seek to expand government power. This can range from nanny state restrictions to full-blown authoritarianism.

With libertarians obviously being a lot closer to the anarchists than communists.

A classic nanny state example is the regulation of alcohol, tobacco and gambling, based on the assumption that people are generally not competent to decide for themselves how much of these to consume. The concept of relative risk is seen as far too complex for all but the smart people in authority to understand.

It is also the reason that governments seek to prevent the publication of so-called misinformation and disinformation, on the grounds that we are too weak minded to recognise it. The assumption that we are prone to perpetual conflict also leads to severe limits on our ownership of firearms, notwithstanding countless examples of naturally peaceful societies.

Those who share Locke’s view, that people get on quite well when left to make their own decisions, arrive at quite different conclusions. The authors of the American Declaration of Independence were strongly influenced by Locke, declaring that certain rights are inherent and the primary purpose of governments is to secure those rights. They also wrote:

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

To Hobbes, the idea of replacing an unsatisfactory sovereign was unthinkable. To Locke, it was obvious. And as he would argue, if we are each responsible for own choices, and accept the consequences of those choices, we are far more likely to enjoy life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

How we decide on the border between the public and private realms is governed by whether we view our fellow humans through the same lens as Hobbes or Locke. In three and half centuries, some things have not changed.

This article was originally published by Liberty Itch.