Table of Contents

Peter MacDonald

William Tyndale grew up near Cheltenham, England, during a time of profound religious unrest. From an early age, he was influenced by his father’s admiration for the early Christian Reformers such as John Wycliffe and Jan Hus: men who had dared to challenge the authority and unbiblical teachings of papal Rome. This legacy of conviction and courage set a fire in young William’s heart for the Word of God.

Gifted with a sharp intellect and a remarkable talent for languages, Tyndale flourished when sent to university. At Oxford and later Cambridge, he mastered Latin and, with further study, acquired Hebrew and Greek, the original languages of the scriptures. This training was no accident: it prepared him for a divine calling far beyond academia.

Tyndale’s passionate preaching and sharp theological insight soon attracted the attention of the church hierarchy. His open-air discussions of scripture with students, grounded not in Latin tradition but in the original Word of God, alarmed the bishop of London and other authorities. He applied for official permission to translate the Bible into English but was flatly denied. Worse, he was warned that any attempt would endanger his life.

But Tyndale was undeterred.

Inspired by Martin Luther’s German Bible, which had flooded into England but was useless to the average English speaker, Tyndale knew what he had to do. He left England in 1524 and traveled to Wittenberg, where he met with Luther and other Reformers. With their encouragement and guidance, particularly from printers like Peter Quentell, Tyndale began the bold task of translating the New Testament into English, not from Latin but directly from the Greek.

A sympathetic Reformation-minded merchant had earlier hired Tyndale to tutor his children, but in reality gave him a safe haven in a manor house where he could begin his translating work. This pattern of hidden patronage from English merchant Reformers and urgent flight continued through his years in exile across Germany, Belgium and the Low Countries. Tyndale was constantly on the move to stay one step ahead of agents sent by the bishop of London and English authorities loyal to Rome.

Tyndale arrived in Europe in 1524 and, by March 1526, he had completed and printed the first English New Testament translated directly from the Greek. It was printed in Worms, Germany, by sympathetic Reformation printers. The books were smuggled into England hidden in bales of cloth, crates of grain and barrels of merchandise, flooding the country with the Word of God in a language the people could finally understand.

In March 2026, we will mark the 500th anniversary of this world changing event: the arrival of the first English New Testament translated from the original Greek, not by a committee, but by one man moved by conviction and guided by God.

But Tyndale’s influence didn’t stop at theology. William Tyndale did more to shape the English language than even William Shakespeare. Phrases we now take for granted “let there be light”, “the powers that be”, “the signs of the times”, “filthy lucre”, “my brother’s keeper” and “fight the good fight” were all Tyndale’s. His Bible didn’t just bring God’s Word to the common man: it forged the very rhythm and clarity of modern English. Unlike Shakespeare, whose language shaped literature, Tyndale’s language was etched into the spiritual and moral vocabulary of English-speaking people for centuries.

For over a decade, Tyndale continued his translating work in secret, constantly updating and refining his New Testament while working on the Old Testament translation. He lived under threat but thrived in adversity with the zeal of a man wholly committed to God.

Tragically, his mission was brought to an end by betrayal. A man named Henry Phillips, an opportunistic criminal, was employed by the bishop of London to find and capture Tyndale. Pretending to be a friend, he gained Tyndale’s trust, then handed him over to the authorities. In 1536, after over a year in prison, William Tyndale was tried and convicted of heresy. He was strangled and then burned at the stake. His final words, reportedly, were: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

God answered that prayer.

Though Tyndale was denied credit in his lifetime, nearly 90 per cent of the King James Bible published in 1611 came directly from his translations. The 47 scholars commissioned by King James drew heavily on Tyndale’s work, especially in the New Testament. Even parts of the Old Testament he translated made it into the final version, though he was never able to complete it, having been martyred.

Tyndale’s blood, along with that of many of his fellow Reformers – men like John Frith and others – was the seed of the English Bible. Today, many modern Christians are rediscovering this forgotten hero of the faith. Thanks to the internet and social media, his story is being told not just in universities or seminaries, but among everyday believers hungry to know the roots of their faith and the cost at which the Bible came into their hands.

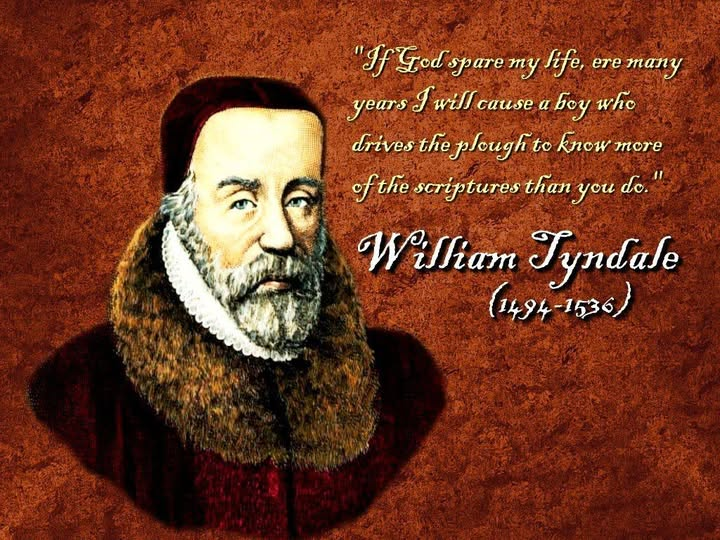

Tyndale once famously said to a papal clergyman: “If God spare my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of the scriptures than thou dost.”

He kept that promise.

And because he did, we read the Bible freely today.

The Legacy in New Zealand.

Tyndale’s Bible also laid the moral and cultural foundation for the freedoms we enjoy in the West today, including here in New Zealand. Our heritage of free speech, conscience and governance under God is rooted in scripture and it all began when the Bible was made accessible to the people.

Those same values reached our shores when Samuel Marsden preached the first Christian sermon on Christmas Day, 1814, in the Bay of Islands. He came not as a coloniser, but as a minister of the gospel, invited by a young Ngāpuhi chief named Ruatara, whose life Marsden had saved years earlier when the chief was destitute in London. Ruatara not only protected Marsden but helped prepare the ground for the gospel to be planted in New Zealand.

And in 1848, when the Free Church of Scotland arrived to found Dunedin, they came not just with hopes of building a city but with the legacy of Tyndale’s Bible in their hearts: a Christian city, shaped by the freedoms and values gifted by God’s Word.

“The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: but the word of our God shall stand for ever.” – Isaiah 40:8

– as translated by William Tyndale.

William Tyndale’s translation didn’t just give England a Bible, it helped shape the English language itself. Many of the following phrases, still in daily use, were coined or popularised by Tyndale in his 1526 New Testament and subsequent Old Testament translations:

1. Let there be light – Genesis 1:32.

- The powers that be – Romans 13:13.

- My brother’s keeper – Genesis 4:94.

- The salt of the earth – Matthew 5:13.

- A law unto themselves – Romans 2:146.

- The signs of the times – Matthew 16:37.

- Filthy lucre – 1 Timothy 3:38.

- The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak – Matthew 26:41.

- Fight the good fight – 1 Timothy 6:12.

- Let not your heart be troubled – John 14:11.

- Ask and it shall be given you – Matthew 7:71.

- Seek and ye shall find – Matthew 7:71.

- Knock and it shall be opened unto you – Matthew 7:71.

- By the skin of your teeth – Job 19:20.

- The meek shall inherit the earth – Matthew 5:51.

- Twinkling of an eye – 1 Corinthians 15:52.

- A thorn in the flesh – 2 Corinthians 12:71.

- Let this cup pass from me – Matthew 26:39.

- The powers that be are ordained of God – Romans 13:12.

- In the beginning was the Word – John 1:1

Tyndale’s work was so foundational to the English language that scholars estimate more than 80 per cent of the New Testament in the King James Version is Tyndale’s phrasing. These weren’t the high speech of scholars: they were the everyday expressions Tyndale deliberately crafted so that ploughboys, mothers and merchants alike could understand the Gospel. His genius was in making truth plain, poetic and powerful and we are still speaking his words 500 years later.