Table of Contents

The next white turnips to wander into this wild, lawless mix of Maori, muskets, traders, sealers, whalers, ex-convicts from Australia, and “adventurers” from all over the world; are missionaries. The saviour of souls.

Samuel Marsden is an Anglican missionary sent from Britain to be a convict chaplain in Australia. On the voyage out he meets Ruatara, a Maori chief from The Bay of Islands, being sent back home on a convict ship (in reduced circumstances). This interests Marsden in the Maori and New Zealand.

The Anglican Missionary Societies direct Marsden to set up a mission station in New Zealand (1808), but because it has such a bad reputation as a wild and dangerous place, the Governor of New South Wales (who also has authority over New Zealand), won’t let him go there. Instead he issues proclamations that every ship leaving Sydney for New Zealand must post a bond with the government not to abuse the Maori or take them off the islands without their permission (1813-14).

Not to be stopped, Marsden hires a ship and sends two missionaries (one of which is Thomas Kendall, also a school teacher), to New Zealand with a hand-mill for grinding corn and a message for Ruatara to return to Sydney with several more chiefs. Ruatara is found, he uses the hand-mill to grind corn he grew from seeds Marsden gave him; and then in 1814 he and several other Bay of Islands chiefs go to Sydney (one of which is Hongi Hika).

The Governor is persuaded that New Zealand needs missionaries. Marsden buys a ship and he, Kendall (who is also appointed Justice of the Peace in New Zealand by the New South Wales Governor), a carpenter missionary, a flax-dresser missionary, their families, eight Maori, two Tahitians, three horses, two cows, one bull and assorted sheep, turkeys, geese and chickens; arrive in Russell where Marsden raises the British flag and delivers the first church sermon in New

Zealand (25 December 1814, the Maori stand up, kneel and sit

down during the service when the white turnips do). “Behold, I

bring you good tidings of great joy”.

Marsden’s second act as a missionary is to negotiate a truce between two warring tribes near Whangaroa, and tell them that he will not supply them with guns and not help them to repair them. But the missionaries do not always set a good example: “I have almost completely turned from a Christian to a heathen”. Marsden buys 200 acres of land for the Missionary Society; but when they also authorise a payment for missionaries to buy personal land at the rate of £50 per missionary child, the Missionary Society suddenly finds that they now have 12 missionaries in New Zealand with 84 children.

THE NEW ZEALAND WARS 1807-1872

The Maori were probably fighting, killing and eating each other in New Zealand from the time they divided up into tribes (fighting and killing each other is one of the Polynesians’ favourite pastimes). There are no written accounts of these fightings and killings because the Maori had no written language. But once the white turnips arrived, they began recording written accounts of the goings on in New Zealand, including the fighting and killing of each other by the Maori (writing written accounts is one of the white turnips’ favourite pastimes). Tasman was the first to record seeing the Maori; and Cook was the first to record seeing their fortified villages, weapons, human sacrifices, and collections of dried human heads.

It is estimated that between the period 1818-1840, the Maori fought some 3,000 battles, sieges and raids; killing some 30,000-80,000 of themselves. Between 1807 (the first recorded account of Maori fighting), and 1872 (the end of the Maori Wars), there were quite a number of different wars fought in New Zealand, with quite a few different names: “The Maori Wars”, “The Maori Civil Wars”, “The Maori Tribal Wars”, “The Musket Wars”, “The Land Wars”, “The Anglo-Maori Wars”, “The Wars of the 3W’s”, “Heke’s War”, “The Flagstaff War”, “The Northern War”, “The Taranaki War”, “The Waikato War”, “The Southern Island War”. It’s complicated keeping all these wars straight. They can be summed up however as “The New Zealand Wars”. The North Island especially, was a pretty warlike place.

The Maori, guns, war and the arrival of missionaries, settlers and the first outside government authority in New Zealand; marks the beginning of the mix of ingredients which will now complicate New Zealand history for the next 58 years.

The British government’s position on New Zealand begins with Cook, but then it just gets more complicated from there: 1769 – James Cook takes possession of the North and South Islands of New Zealand in the name of King George III. 1814 – The New South Wales Governor appoints a Justice of the Peace for New Zealand on behalf of the British government. 1817, 1823, 1828 – The British government states that “New Zealand is not within His Majesty’s Dominions”. 1823-1831 – The British government passes laws to punish crimes committed in New Zealand by British subjects, including the trading of dried human heads (punishable by a fine and having the heads returned “to whom they belonged”). The Maori purposely tattooed the heads of slaves so they would be more valuable in the trade market when the heads were eventually separated from their bodies. Supply and demand. The Maori were always quick to catch on to a business opportunity. This confusion will just continue as step by step the British government becomes more entangled in New Zealand.

Thomas Kendall wants to learn the Maori language, so he begins sounding out their words and writing them down in English, producing a small Maori dictionary he calls “The New Zealander’s First Book” (1815).

In 1820 Kendall takes two Maori chiefs with him to Britain (one of which is Hongi Hika), and together with Professor Samuel Lee of Cambridge University, they compile “A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand”, which becomes the foundation of a written Maori language.

The New Zealand missionaries then begin translating the Bible into Maori (1834); The Church Missionary Society sends a printing press to New Zealand; and the first Maori Bibles, Prayer Books and “Dictionary of the Maori Language” are published (1844, the Maori language uses only 15 of the 26 letters of the English alphabet).

Place Names In New Zealand

The Dutch may have given New Zealand its country name, but they didn’t give it very many place names. There are something like 4,682 place names in New Zealand, but only two of them are Dutch. The rest are either English (57%) or Maori (43%).

But on the North Island about 78% of all the place names are Maori (South Island 28%). Being on the North Island of New Zealand is like being in a foreign country with a foreign language (something like being in Wales). But it’s a foreign language in English. A foreign language with tricky vowels, consonants and dipthongs. A foreign language not meant to be completely sounded out in English, but which you’ll probably end up doing anyway. Like Welsh. A fun foreign language.

There are something like 2,021 Maori place names in New Zealand. Of these 78% begin with one of only six letters (K, M, O, P, T, W). Altogether in New Zealand (Maori and English place names), 50% of them begin with only these six letters (“W” is the most common letter, 20% of all the place names in New Zealand begin with the letter “W”).

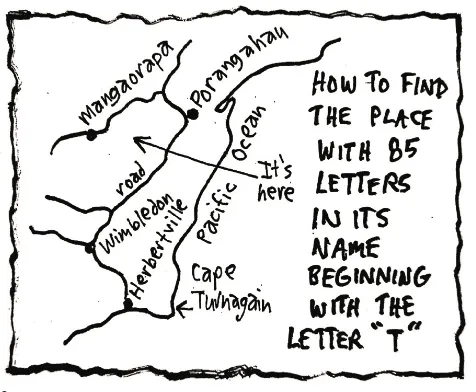

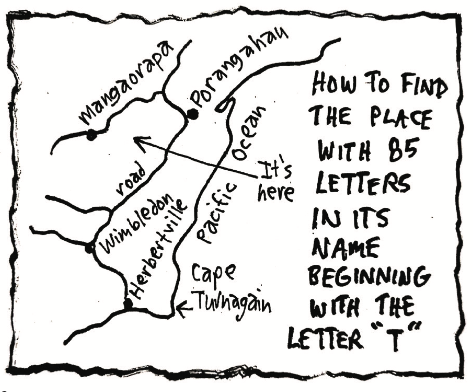

However, although the Maori language uses only 15 of the 26 letters of the English alphabet, the letters it does use, it uses a lot. There is a ridge or hill just north of Cape Turnagain on the east coast of the North Island, that has a name that in its elongated version is 85 letters long. In its original shorter version it has 57 letters, which makes it just two letters shorter than the elongated version of a place in Wales with 59 letters in its name (original version 20 letters).

The Maori place with all the 85 letters means: ”The place where Tamatea, the man with the big knees, who slid, climbed and swallowed mountains, known as Landeater, played his flute to his loved one” (or words to that effect).

The Maori language has had quite an influence on New Zealand. An oral language converted into the written English alphabet. And out of it comes place names like: Whangaparapara, Whakamaramara, Waerengoakuri, Whakaangiangi, and the one that has 85 letters in it beginning with the letter “T”. A foreign language. A foreign language for an English-speaking Polynesian country with a Dutch name.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part Two

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Three

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Four

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part One