Table of Contents

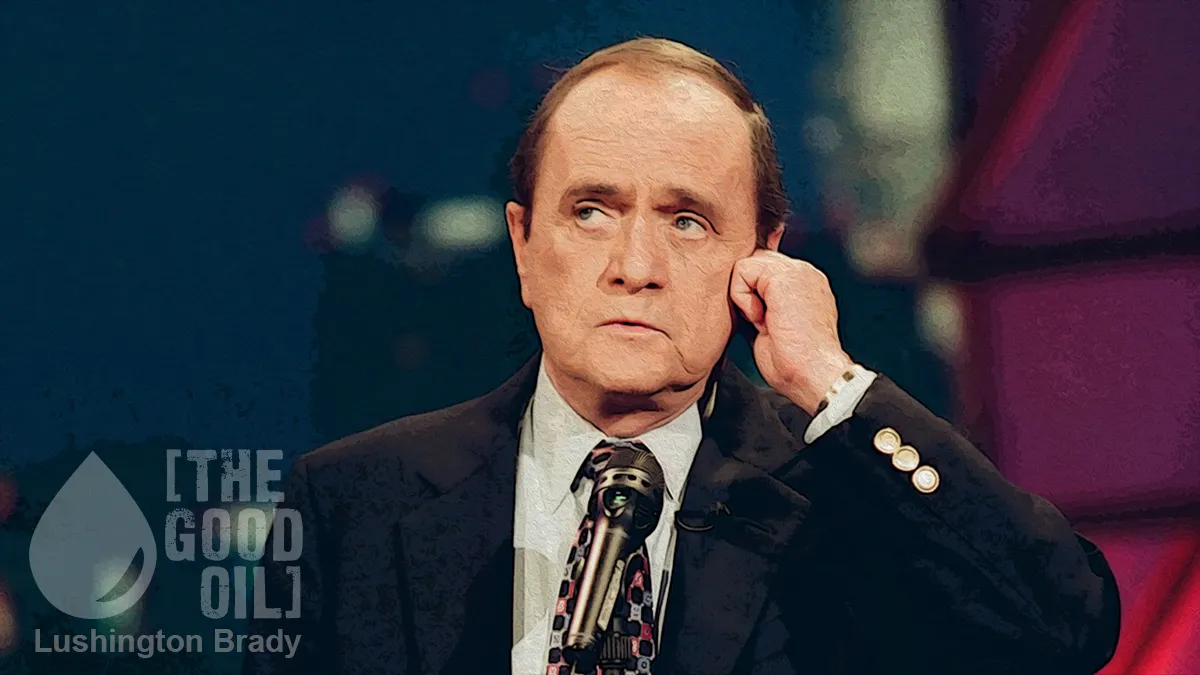

When you see a beloved celebrity’s name trending on X, it’s usually a heart-sinking, Oh, no… moment. Because it usually means that they’re either a) dead or b) exposed as a monster. But when Bob Newhart’s name trended on occasions over the last few years, it was usually assumed to be the former (he was in his 90s, after all). In fact, it was for neither reason: it was just a whole bunch of people suddenly remembering at once how much they loved the “button-down” comedian.

But no-one can hold off the Grim Reaper forever. And so the announcement came, this week, that everyone had been dreading.

Bob Newhart, who burst onto the comedy scene in 1960 working a stammering Everyman character not unlike himself, then rode essentially that same character through a long, busy career that included two of television’s most memorable sitcoms, died on Thursday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 94.

His publicist, Jerry Digney, confirmed the death.

Newhart’s career spanned so many decades that he was known and loved by generations for so many different things, from his groundbreaking comedy album The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart (the first comedy album to win the Grammy for album of the year), to The Bob Newhart Show in the ’70s, to “Papa Elf” in the 2003 Will Ferrell breakout movie, Elf.

Quite a run of achievements for perhaps the unlikeliest of comedians: Newhart rocketed from being an unknown accountant making home tapes to amuse himself in 1959, to beating Nat King Cole, Harry Belafonte and Frank Sinatra for Album of the Year in 1961.

He was born George Robert Newhart in Oak Park, Illinois on September 5, 1929. His father was also named George, hence Bob becoming known by his middle name. George David Newhart and his wife, Pauline, had three other children as well, all girls, and sent Bob and his sisters, Virginia, Mary Joan and Pauline, to Roman Catholic schools in the Chicago area. His family’s modest background led Newhart to later write that they couldn’t afford to go to Florida on holiday to escape the harsh Illinois winters. “If we went on vacation, it was to Wisconsin.”

After dropping law school, Newhart graduated from Loyola University with degrees in business management and accounting. “I was never a certified public accountant,” he said. “I just had a degree in accounting. The reason I was never a certified public accountant was because it would require passing a test, which I would not have been able to do.”

He served two years stateside in the army during the Korean War then held down several accounting jobs in Chicago. He often related his habit of balancing the petty cash drawer at the end of the day by making up shortfalls out of his own wallet or pocketing any overage. It was during a stint with the Glidden Company that he and a friend in another department, Ed Gallagher, resorted to relieving the tedium of office work by calling each other and improvising comic dialogues.

In 1956, they tried recording some of these routines and marketing them to radio stations, but their client base was never very large, and the unprofitable venture ended when Mr. Gallagher took a job in New York. This led to Newhart’s signature style: solo routines spoken to an unheard, invisible partner (often on a telephone). It was left to the audience to imagine the other half of the conversation.

One such classic involves the head of the West Indies Company at home in England taking a long-distance call from Sir Walter Raleigh, extolling tobacco and coffee.

Y’see, Walt... I think you’re gonna have rather a tough time selling people on sticking burning leaves in their mouths... It’s going very big over there, is it?... What’s the matter, Walt?... You spilt your what?... Your coff-ee? What’s coffee, Walt?... That’s a drink you make out of beans, huh?

The tapes caught the ear of Chicago radio personality Dan Sorkin and some local radio and television work followed. Sorkin also passed the tapes on to George Avakian, an executive at Warner Bros. Records. Avakian asked Newhart to let Warners record his next nightclub performance.

There was only one problem: Newhart had never actually performed in front of an audience.

A hastily recruited agent eventually booked him into the Tidelands Motor Inn in Houston, where, on Feb 10, 1960, “The Button-Down Mind” was recorded.

“I came off and walked by the maitre d’s table,” Mr Newhart told The Houston Chronicle in an interview for the 50th anniversary of that recording. “He said: ‘Go back out. They’re still applauding.’ And I said, ‘But that’s all I have.’ He said, ‘Well, go back out.’ So I walked back out and said, ‘Which one would you like to hear again?’”

The resulting record shot to No. 1, won three Grammies, and prompted Playboy to declare him the “best new comedian of the decade”. “Of course, there were still nine more years left in the decade,” Newhart later observed.

Unlike many entertainers who achieve fame almost overnight, Mr Newhart was able to handle the unexpected success of the “Button-Down Mind” albums. He transitioned quickly and easily into television, landing a short-lived variety show, numerous guest appearances on the shows of Dean Martin and Ed Sullivan, regular work guest-hosting for Johnny Carson on “The Tonight Show” and, ultimately, “The Bob Newhart Show,” a celebrated sitcom in which he played a somewhat befuddled psychologist.

That series ran from 1972 to 1978, and in 1982 he followed it up with “Newhart,” another successful sitcom, in which he played a Vermont innkeeper. “Newhart” ran for eight seasons and ended with what is still viewed as one of the greatest finales in television history.

Newhart kept working in film and television well into his 80s. His role in Elf introduced him to a new generation of kids at the same time as evoking fond memories for their parents and grandparents. In fact, Newhart ranked Papa Elf as his best role, “by far”.

“My agent sent me the script and I fell in love with it,” he said, later adding that he told his wife that the movie was “going to be another ‘Miracle on 34th Street,’ where people watch it every year.”

“In my opinion, there has not been anything like it in the interim,” he added. “People wanted to believe in it. … People need that charming, wonderful thing about the Christmas spirit and its way of powering the sleigh.”

As the kids who saw Elf grew older, they saw Newhart again, in a memorable series of guest appearances as “Professor Proton”, in hit show The Big Bang Theory. He reprised the role most recently as a voice-over in Big Bang Theory prequel, Young Sheldon.

In 1993, Newhart was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1993, and has had his material added to the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. He won the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 2002. Honours that he received with typical self-deprecating style:

“I think the whole awards-giving process needs rethinking,” he wrote. “For starters, they should bestow lifetime achievement awards at the beginning of a performer’s career. This way the person can still enjoy it while he is young, rather than giving it to him when he has lost most of his marbles and is standing onstage wondering why all these overdressed people are applauding.”

Mr Newhart is survived by his four children, Robert Jr, Timothy, Courtney Albertini and Jennifer Bongiovi; a sister, Ginny Brittain; and 10 grandchildren. Virginia “Ginnie” Newhart, his wife of 60 years, passed away last year.