Table of Contents

Ani O’Brien

Like good faith disagreements and principled people. Dislike disingenuousness and Foucault. Care especially about women’s rights, justice, and democracy.

The revolution is eating itself. Te Pāti Māori, the so-called uncompromising voice of Māori sovereignty, is turning inward, and the implosion is happening in real time. The movement that lectured parliament about tikanga and collective leadership can’t seem to practise either. The façade of unity has cracked and beneath it lies a mess of ego, dysfunction, and factions.

The fractures have gone from rumour to reality. Two key developments have confirmed that the whare of Te Pāti Māori is visibly crumbling. These developments being Toitū Te Tiriti’s public split from Te Pāti Māori and open dissent coming from within the party’s own caucus.

Toitū Te Tiriti has been an ally of Te Pāti Māori since it was formed by Te Pāti Māori operatives, but now it has officially cut ties with the party. In a statement reported by Te Ao News, spokesperson Eru Kapa-Kingi cited leadership failings, an “ego-driven narrative”, and the erosion of constitutional accountability as reasons for walking away. He accused the party of operating under a “dictatorship model”, of failing to hold AGMs or convene its national council as required, and of centralising power in a way that betrays its grassroots kaupapa. This is not the language of a friendly parting. It is a declaration of no confidence in Te Pāti Māori’s current leadership and direction.

The breakaway came on the same day 1News reported internal dissent from within the caucus itself. Eru’s mother, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi, the MP for Te Tai Tokerau, publicly criticised what she also described as “dysfunction” following her recent demotion from the party whip role. The position was quietly transferred to co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, a move that caught some in the party off-guard. The elder Kapa-Kingi’s comments were restrained but pointed: a clear signal that something is very wrong inside Te Pāti Māori’s parliamentary wing. When MPs start using words like “dysfunction”, it’s rarely an isolated gripe. More likely a symptom of deeper discontent.

These ruptures suggest a systemic crisis. And one figure’s absence from the public stage makes it even more glaring. Co-leader Rawiri Waititi has effectively vanished from view. The last time he appeared on Te Pāti Māori’s social media (Instagram and Facebook) alongside co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer was on August 28, promoting then by-election candidate Orinii Kaipara. His last solo appearance was on July 22. Since then, all official communications and press releases have either been issued in Ngarewa-Packer’s name or under the party’s collective banner. For a co-leader who once embodied the party’s activist spirit and rhetorical fire, such silence is deafening. Whether he’s been sidelined, withdrawn voluntarily, or is simply no longer in control, the optics are terrible. A party built on the symbolism of dual leadership is now operating, effectively, as a one-woman show.

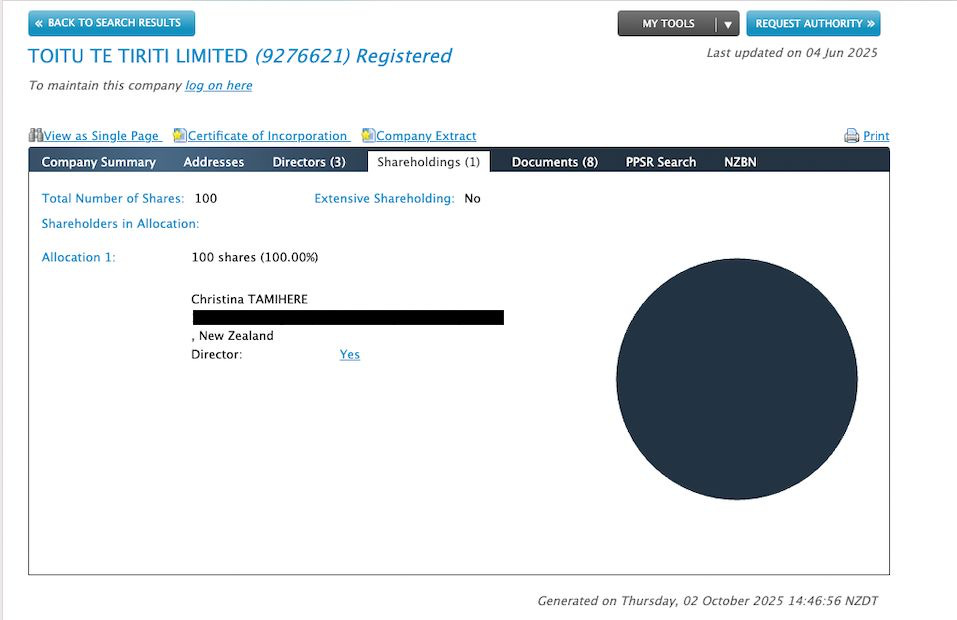

That brings us to one of the most intriguing and under-examined players in this unfolding drama: Kiri Tamihere-Waititi. She occupies two key positions: general manager of Te Pāti Māori and sole shareholder of Toitū Te Tiriti, the very organisation that has just severed ties with the party. Her dual role places her squarely in the eye of the storm. According to Te Ao News, Tamihere-Waititi was unable to attend the meeting where Toitū’s leadership voted to disaffiliate, but her absence only adds to the mystery. If she controls the entity that has now walked away from Te Pāti Māori, where does that leave her loyalties? Is she a bridge between movement and party, a silent broker of power, or now caught between two warring factions?

Of course, the fact that she is the daughter of the president of Te Pāti Māori John Tamihere and the wife of missing-in-action co-leader Rawiri Waititi only adds to the intrigue.

The contradictions are almost Shakespearean. On paper, the party’s general manager and the movement’s owner are one and the same and yet the movement has publicly rebuked the party. It raises serious questions about who is actually running what, and whose mandate Tamihere-Waititi is acting on. If Toitū’s move was genuinely grassroots, it represents a stunning rebuke of her own operational leadership. If it was strategic, it may signal an attempt to preserve credibility by separating kaupapa activism from a party mired in internal strife. Either way, it exposes a structural flaw. When power is so centralised that one person sits atop both the political and activist wings, any fracture reverberates through the whole edifice.

What we are witnessing is the inevitable collision between movement vibes and party structure. Movements thrive on horizontality, collective accountability, and moral authority. Vibes. Parties, by contrast, demand message discipline, hierarchy, and brand management. Structure. For a while, Te Pāti Māori managed to straddle both worlds, projecting radical authenticity while operating within parliamentary constraints. That balancing act appears to have failed. The grassroots now accuse the party of failing to observe tikanga and surrendering to ego and control.

The consolidation of communications around Debbie Ngarewa-Packer’s name hints at a deliberate re-branding strategy or a power grab. By pushing out press releases solely in her voice, the party may be trying to project order and unity amid the chaos, but what once looked like shared leadership now feels like a hollow title.

The danger for Te Pāti Māori is twofold. First, credibility. Radical Māori politics depends on authenticity: on being seen as of, by, and for, the people. When allies like Toitū Te Tiriti walk away citing breaches of kaupapa, that moral authority evaporates. Second, fragmentation. Disillusioned activists and members may splinter off into new formations or re-energise non-parliamentary movements. In trying to control the narrative, Te Pāti Māori risks losing the movement energy that made it powerful.

What happens next will determine whether this is a temporary crisis or a full implosion. We may see resignations, formal complaints over constitutional breaches, or even the birth of a rival Māori political entity. That certainly is a possibility that can be read between the lines of Eru Kapa-Kingi’s comments. We may also see a hardening of control, a purge of dissent, a tightening of the brand, a further withdrawal of transparency. In all of it, Kiri Tamihere-Waititi will be worth watching closely. Her next moves could reveal whether this rupture was accidental, strategic, or inevitable.

One thing is clear: this is no longer just gossip. The project of radical Māori politics, the politics of tino rangatiratanga, decolonisation, and mana motuhake, relies on cohesion, a popular mandate, and good vibes. When movements lose faith in a party that claims to speak for them, the whole edifice begins to collapse.

This article was originally published by Change My Mind.