Table of Contents

We’ve all seen them¹. If you’ve ever had to read or write academic writing, they’ve probably been the bane of your existence.

Footnotes².

As Robert Anton Wilson wrote, in his novel The Widow’s Son, footnotes are often used in a recursive fashion by mendacious and inferior scholars, in order to lend a depth of pseudo-profundity to what are really transparently thin arguments³. But where and when did footnotes come from?⁴.

“The history of the footnote may well seem an apocalyptically trivial topic,” writes historian Anthony Grafton. “Footnotes seem to rank among the most colorless and uninteresting features of historical practice.” And yet, Grafton – who has also written The Footnote: A Curious History (1999) – argues that they’re actually pretty important.

“Once the historian writes with footnotes, historical narrative becomes a distinctly modern” practice, Grafton explains. History is no longer a matter of rumor, unsubstantiated opinion, or whim.

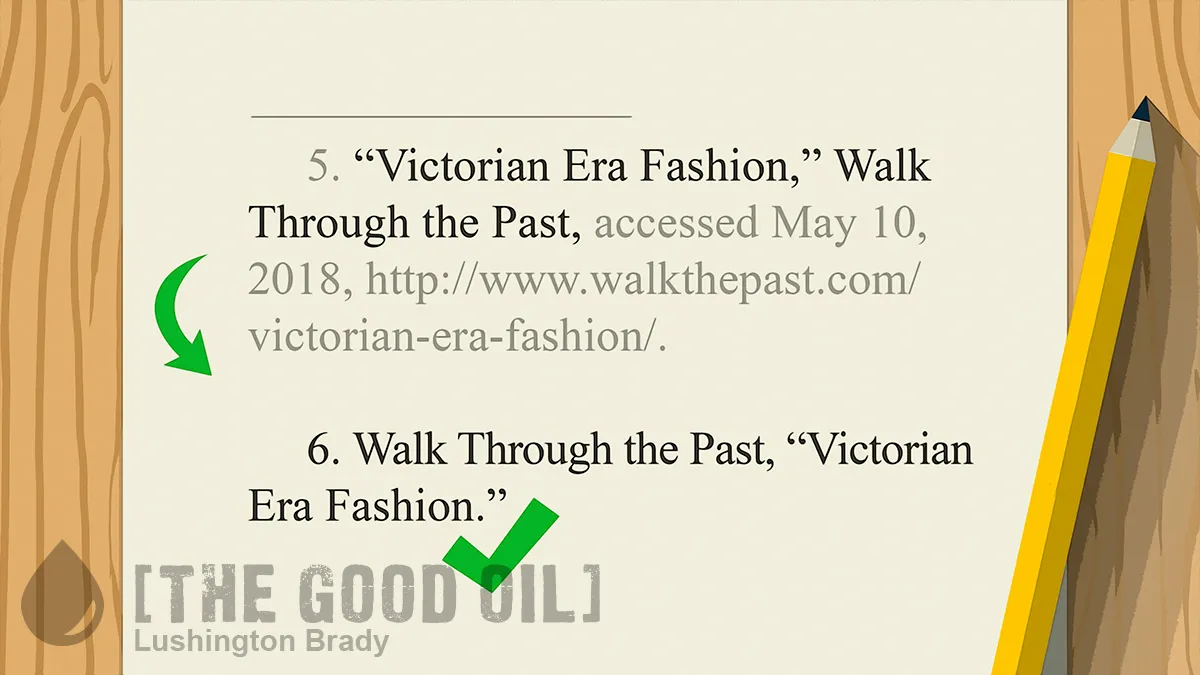

According to Grafton, “the text persuades, the note proves”. The beauty of a footnote, properly used, is that it conveys extra information, often confirmatory, without interrupting the readability of the text itself. The footnote can be used, for example, to cite the source of a claim.

On the other hand, as I probably successfully proved above, footnotes can be annoying and trivial. Existing, indeed, to do nothing but lend an air of pseudo-profundity to a thin text.

Who is responsible for all this?

Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886), the founder of source-based history, is usually credited with the “invention” of the scholarly footnote in the European tradition. Grafton describes von Ranke’s theory as sharper than his practice: his footnoting was much too sloppy to be a model for scholars today. But various forms of footnotes were used long before von Ranke. Sources were of vital importance to both Roman lawyers and Christian theologians in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, as they strove to back up their own arguments with the weight and gravitas of others.

The true, modern, footnote, “with its full bibliographical details, discussion of variant texts and sources, and separate place on the page […] seems to have arrived at its definitive form in the later 17th century”. In particular, Pierre Bayle’s Historical and Critical Dictionary of 1697 is a key text. Bayle’s dictionary was packed with, not just footnotes, but footnotes to footnotes. In fact, within a few decades Bayle’s imitators were a target of satire.

Grafton has a candidate for the longest known footnote: it’s 165 pages long and found in John Hodgson’s 1840 History of Northumberland. The award for the Most Ironic Footnotes goes to Edward Gibbon, who plays it straight in the text of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (published between 1776 and 1789) and then adds the snark to the footnotes, playfully undermining the seriousness of the endeavor above.

While footnotes are too often abused by bad academic hacks, they serve an essential function for historians, biographers, science writers and anyone else who wants their reader to trust their veracity. For the modern, online, writer, judicious hyperlinks perform the same function. Do we claim someone said or did something? Link to a tweet, a video, a blog post, or news report that proves it.

“Footnotes give us reason to believe that their authors have done their best to find out the truth […they ] ‘democratize scholarly writing’ both by bringing in other voices to the conversation and by including the reader. This makes every reader part of the argument, as well as, at least in theory, a fact-checker. Few readers will dig deeply into the notes, but the notes should nonetheless provide the back-up to controversial points and questionable facts.”

Nullius in verba, after all: ‘Take no one’s word for it’. Or, as Ann Coulter says, “Show us the whole video”. If the media want to tell us that Donald Trump “praised neo-Nazis”, link us to the relevant speech. The whole thing, not just a cherry-picked version slanted to fit a narrative.

The footnote (or the link) is, or ideally should be, the proof.

¹ Footnotes.

² These things.

³ The joke was that this was itself a footnote in a book riddled with trivial footnotes.

⁴ I’ll stop now.