Table of Contents

Mark Rickerby

Lecturer, School of Product Design, University of Canterbury

The incident of a woman misidentified by facial recognition technology at a Rotorua supermarket should have come as no surprise.

When Foodstuffs North Island announced its intention to trial this technology in February, as part of a strategy to combat retail crime, technology and privacy experts immediately raised concerns.

In particular, the risk of Maori women and women of colour being discriminated against was raised, and has now been borne out by what happened in early April to Te Ani Solomon.

Speaking to media this week, Solomon said she thought ethnicity was a “huge factor” in her wrongful identification. “Unfortunately, it will be the experience of many Kiwis if we don’t have some rules and regulations around this.”

The supermarket company’s response that this was a “genuine case of human error” fails to address the deeper questions about such use of AI and automated systems.

Automated decisions and human actions

Automated facial recognition is often discussed in the abstract – as pure algorithmic pattern matching, with emphasis on assessing correctness and accuracy.

These are rightfully important priorities for systems that deal with biometric data and security. But with such crucial focus on the results of automated decisions, it’s easy to overlook concerns about how these decisions are applied.

Designers use the term “context of use” to describe the everyday working conditions, tasks and goals of a product. With facial recognition technology in supermarkets, the context of use goes far beyond traditional design concerns such as ergonomics or usability.

It requires consideration of how automated trespass notifications trigger in-store responses, protocols for managing those responses, and what happens when things go wrong. These are more than just pure technology or data problems.

This perspective helps us understand and balance the impact of engineering and design interventions at different levels of a system.

Investing in improving prediction accuracy seems an obvious priority for facial recognition systems. But this has to be seen in a broader context of use where the harm done by a small number of wrong predictions outweighs marginal performance improvements elsewhere.

Responding to retail crime

New Zealand is not alone in reported increases in shoplifting and violent behaviour in stores. In the UK, it has been described as a “crisis”, with assaulting a retail worker now a standalone criminal offence.

Canadian police are funnelling extra resources into “shoplifting crackdowns”. And in California, retail giants Walmart and Target are pushing for increased penalties for retail crime.

While these problems have been linked to the rising cost of living, industry group Retail NZ has pointed to profit-seeking organised crime as the major factor.

Sensationalised coverage using security footage of brazen thefts and assaults in stores is undoubtedly influencing public perception. But a trend is difficult to measure due to a lack of consistent, impartial data on shoplifting and offenders.

It is estimated that 15-20% of people in New Zealand are affected by food insecurity, a problem found to be strongly associated with ethnicity and socioeconomic position. The links between cost of living, food insecurity and black market distribution of stolen groceries are likely to be complex and nuanced.

Caution is therefore needed when assessing cause and effect, given the risks of harm and implications for civil society of a shift towards constant surveillance in retail spaces.

AI and human bias

Commendably, Foodstuffs has engaged with the Privacy Commissioner and has been transparent about safeguards in biometric data collection and deletion protocols. What’s missing is more clarity around protocols for the security response in stores.

This is more than about customers consenting to facial recognition cameras. Customers also need to know what happens when a trespass notification is issued, and the dispute resolution process should a misidentification occur.

Research suggests human decision makers can inherit biases from AI decisions. In situations of heightened stress and risk of violence, combining automated facial recognition with ad-hoc human judgement is potentially dangerous.

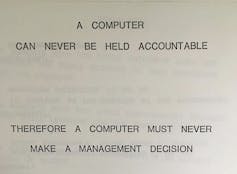

Rather than isolating and blaming individual workers or technology components as single points of failure, there needs to be more emphasis on resilience and tolerance for error across the whole system.

AI errors and human errors cannot be avoided entirely. AI security protocols with “humans in the loop” need more careful safeguards that respect customer rights and protect against stereotyping.

Shopping and surveillance

Australian supermarkets have responded to retail crime with overt technological surveillance: body cameras issued to staff (also now adopted by Woolworths in New Zealand), digitally tracking customer movement through stores, automated trolley locks and exit gates to prevent people leaving without paying.

Supermarkets may now be at the forefront of a technological shift in the shopping experience. Moving towards a surveillance culture where every customer is monitored as a potential thief is reminiscent of the ways global airport security changed after 9/11.

New Zealand product designers, software engineers and data scientists will be paying close attention to the outcome of the Privacy Commissioner’s review of the Foodstuffs facial recognition trial.

Theft and violence is an urgent problem for supermarkets to address. But they now need to show that digital surveillance systems are a more responsible, ethical and effective solution than possible alternative approaches.

This means acknowledging technology requires human-centred design to avoid misuse, bias and harm. In turn, this can help guide regulatory frameworks and standards, inform public debate on the acceptable use of AI, and support development of safer automated systems.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.