Table of Contents

If you ask people who watch a lot of television who the smartest scientist in history was, they’ll almost certainly say either Stephen Hawking or, God help us, Neil deGrasse Tyson. If you’re lucky, they might recall Albert Einstein. But, while at least Hawking was undoubtedly very smart, and Einstein one of the great scientists, there was one who was entitled to snort, like Vizzini in The Princess Bride, “morons”.

And most people have never heard of him.

Yet he was a polymath whose accomplishments in physics, mathematics, engineering and computer science were “beyond astonishing”. He was a pioneer in quantum physics and digital computers, did much of the mathematical computation at the heart of the first atomic bombs, was the Pentagon’s leading defence scientist, and laid the basics in digital processing necessary for such modern technologies as mobile phones.

He also pioneered the concept of open source computing and insisted – sometimes by taking vendors to court – that all his innovations were free, unlicensed and for mankind.

But possibly my favourite story of his life is how he used to drive Einstein nuts, when they had adjoining offices at Princeton. Where Einstein preferred a quiet working environment, this particular genius preferred to work surrounded by noise and chaos. The German marching band music he particularly liked to play resounded through the walls partitioning his and Einstein’s office.

His name was John Von Neumann, and it’s no exaggeration to say he changed the world.

Von Neumann was born to wealthy parents (his father knew the king) in Budapest at the end of 1903. It was then the capital of the 1000-year-old kingdom of Hungary that was soon to be violently convulsed by the events of World War I.

He was taught in several European languages, including English and French as well as Latin and Ancient Greek, and exhibited prodigious powers of mental computation; aged six, he could divide one eight-digit number by another. His two younger brothers were also very bright, but John stood out in a crowded family field.

When Von Neumann was born, German historian Wilhelm Oncken had not quite completed his landmark 46-volume history of antiquity, the Middle Ages and modernity. By 12, Von Neumann had read them all and three years on was studying advanced theoretical calculus. Before the age of 20 he was the author of landmark papers on maths.

Still, his father thought his prodigious intellect would have better financial prospects in a more grounded trade: chemical engineering. A course which Von Neumann completed at Berlin University while simultaneously finishing a PhD at home in Budapest. He was turning out mathematics papers every few weeks.

A Jewish-born Catholic convert, Von Neumann fled Europe for America, like so many academics, as his home descended into the dark valley of the 1930s.

At Princeton, he made a name for himself, not just for bugging Einstein, but as an immaculate dresser and terrible driver.

“I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like Von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man”

He could never really drive and it was reported that he bribed the New Jersey examiner to secure his licence. Once he was making good money he loved to buy Cadillacs at about $200,000 a pop in today’s money. They never lasted long. As Von Neumann explained following another accident: “I was proceeding down the road (and) the trees on the right were passing me in orderly fashion at 60 miles an hour. Suddenly one of them stepped in my path. Boom!”

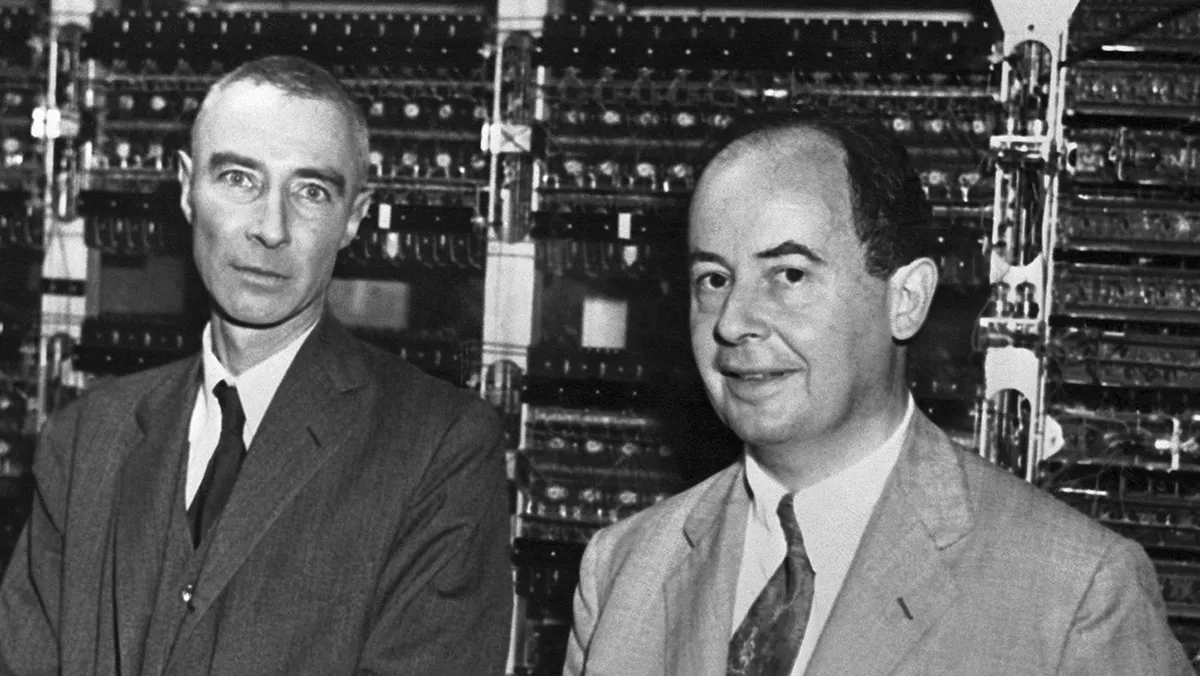

But his enduring and unmatched genius was the key to him and to the regard in which he was held by some of the towering intellects of the 20th century, Einstein, Britain’s code-breaking genius Alan Turing and Manhattan Project director Robert Oppenheimer among them. Some of them believed Von Neumann the smartest human ever.

Last year’s star-studded blockbuster film Oppenheimer about the “father of the atomic bomb” – which has 13 nominations at Monday’s Academy Awards – unaccountably excluded Von Neumann, perhaps because his achievements may have overshadowed its star. Oppenheimer would have been appalled.

No less a scientific luminary than Hans Bethe (another far from household name), who worked alongside Oppenheimer and Von Neumann at Los Alamos, and won the Nobel prize for physics, remarked that, “I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like Von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man”.

In 1955, Von Neumann was diagnosed with malignant cancer, possibly linked to radiation exposure at Los Alamos. Within two years, he was dead.

He could work dispassionately with numbers, physics, theories and even bombs, but he was frightened of death, and spoke to his mother about the possibility of a hereafter, explaining that he believed it likely there was a God. “Many things are easier to explain if there is than if there isn’t,” he told her […]

His simple headstone at Princeton records nothing of his monumental achievements, even though our world could not function without them.

The Australian